ALABAMA MINES

The discovery of coal along Alabama's rivers can be traced back to 1815, when several veterans of the Battle of New Orleans made their way into present-day central Alabama. In the 1820s, Levi Reid and James Grindle settled at the Locust Fork of the Warrior River, where they found plentiful coal deposits. Early accounts suggest that numerous citizens of Bibb, Blount, Jefferson, Shelby, Tuscaloosa, and Walker counties collected coal from this region as early as the 1830s.

Ultimately four coal fields developed in Alabama, the Warrior, the Cahaba, the Coosa, and the Plateau. These deposits represent the southern end of the Appalachian coal field, which spans nearly 70,000 square miles and extends from Pennsylvania and Ohio to central Alabama.

Later historical summaries, based on reports by state geologist Michael Tuomey in the 1850s, indicated that the first systematic underground mining occurred in the Cahaba field near Montevallo in 1856. Most accounts identify the Alabama Coal Mining Company (ACMC) as the first coal-mining enterprise in that area, but personal records indicate that William Phineas Browne, founder of the Little Cahaba Iron Works, used slave labor to mine coal in the Montevallo area as early as 1849.

During the Civil War, most of the coal supplied to the Confederacy came from Bibb, Jefferson, Shelby, St. Clair, Tuscaloosa, and Walker counties. Alabama's coal and iron industries were devastated in the spring of 1865, however, during a series of cavalry raids by Union forces under General James H. Wilson.

Despite numerous attempts to rebuild the state's industries, coal mines remained relatively dormant until the mid-1870s, when Alabama's economy began to recover. In 1872, the Louisville and Nashville Railroad (L&N) completed construction of a main line that connected the Alabama River at Montgomery with the Tennessee River at Decatur. Railroad officials hoped to link Red Mountain iron ore with the coal of the Cahaba field to promote iron production.

In 1873, industrialist Daniel Pratt and his son-in-law Henry F. DeBardeleben purchased the Oxmoor furnace in an effort to rebuild central Alabama's industrial economy. Shortly thereafter, ironmaster Levin S. Goodrich and the Eureka Mining and Transportation Company of Alabama initiated tests to increase production efficiency by reducing the consumption of coal and expanding iron output. He found that coke—a light, porous by-product created when coal is baked for 48 to 72 hours at high temperatures in glazed firebrick (beehive-shaped) ovens—was a better fuel for producing iron. These experiments culminated in the production of coke iron on March 11, 1876, and in Goodrich's determination that Warrior field coal was the most suitable for making coke.

DeBardeleben, together with other early Alabama industrialists Truman H. Aldrich and James W. Sloss, formed the Pratt Coal and Coke Company in 1878. With Squire's assistance, the group opened several slopes and built the Birmingham & Pratt Mines Railroad to link their supply of coking coal with the furnaces of the Birmingham District. These mines would feed the Birmingham iron industry and eventually spawn the development of the mining community known as Pratt City.

As the national economy improved, other investors became interested in Birmingham's coal and iron industry. The Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company (TCI) purchased Ensley's Pratt Coal and Iron Company in 1886. With this takeover, TCI acquired the Pratt mines (which produced more than 3,000 tons of coal daily), two furnaces (and four more under construction), 1,210 coke ovens (with 1,800 under construction), 76,056 acres of coal lands, and 12,204 acres of ore properties. During the coal strike of 1894, the Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad company employed private enforcement officers, known as the Erskine Ramsay Guards (named for the company's innovative chief engineer), to police its Pratt Mines and threaten striking miners.

The Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company (1852–1952), also known as TCI and the Tennessee Company, was a major American steel manufacturer with interests in coal and iron ore mining and railroad operations. Originally based entirely within the state of Tennessee, it relocated its headquarters to Birmingham, Alabama in 1895, from then onwards operating almost exclusively around the Birmingham region. With a sizable real estate portfolio, it owned the Birmingham satellite towns of Ensley and Fairfield, where it located two large steel mills, the latter employing a peak of upwards of 4500 workers during World War II.

Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad was founded as the Sewanee Furnace Company, a small mining concern established in 1852 by Nashville entrepreneurs seeking to exploit Tennessee's rich coal reserves and the 19th century railroad boom. After losing money the business was sold to New York investors in 1859, and was reorganized as the Tennessee Coal and Rail Company, but the outbreak of the Civil War the following year and the severing of ties between North and South saw the fleeting company repossessed by local creditors. It became Tennessee's leading coal extractor over the next decade, mining and transporting coal around the towns of Cowan and Tracy City in the Cumberland Mountains of Tennessee, and soon branched out into coke manufacture.

Thomas O'Connor purchased the company in 1876 and expanded the business into iron manufacture in order to stimulate coke sales, building a blast furnace near Cowan. The business was subsequently renamed the Tennessee Coal, Iron, and Railroad Company. TCI never again changed its name, despite a later expansion into Alabama following the 1886 purchase of the Birmingham-based Pratt Coal and Iron Company. Such was the industrial importance of Alabama to TCI that in 1895, in recognition of the ascendancy of the region over Tennessee, the company relocated its offices to Birmingham.

The Birmingham District is a geological area in the vicinity of Birmingham, Alabama where the raw materials for making steel, limestone, iron ore, and coal are found together in abundance. The district includes Red Mountain, Jones Valley, and the Warrior and Cahaba coal fields in Central Alabama. As the iron and steel industry of the Birmingham District tapped coal reserves from the Warrior field, many individual investors sought their fortunes among Alabama's "black diamonds." Red Mountain is a long ridge running southwest-northeast and dividing Jones Valley from Shades Valley south of Birmingham, Alabama. It is part of the Ridge-and-Valley region of the Appalachian mountains. The proximity of Red Mountain's iron ore to nearby sources of coal and limestone was the impetus to develop and promote the Birmingham District as an industrial site.Once established, these coal-mining ventures attracted waves of workers and their families.

Coal mining operations enjoyed high demand and constant work during World War I and World War II. The introduction of improved mechanization made surface mining a more profitable undertaking than underground mining. By the 1950s, coal markets were in severe decline, however, and most of Alabama's mines closed. Some operations continued, but most were constrained by newly enacted environmental protection laws, land reclamation expenses, safety regulations, and rising labor costs. Ultimately, less expensive extraction methods and cheaper labor offset transportation costs and prompted many coal companies to look to other states.

Miners' houses near Birmingham, AL 1935

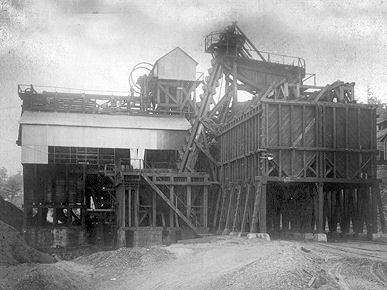

Debardeleban Coal Co. Mine - St. Clair Co., AL

Warner Coal Mine - Birmingham, AL

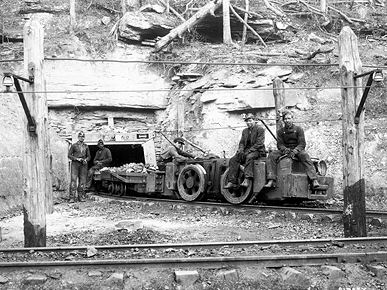

Warner Coal Co. slope mine entrance - Republic, Jefferson Co., AL

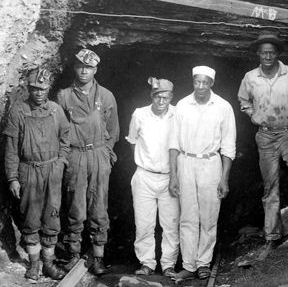

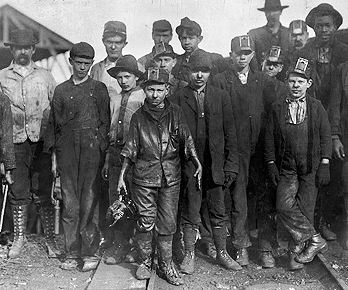

Walker County, Alabama coal miners

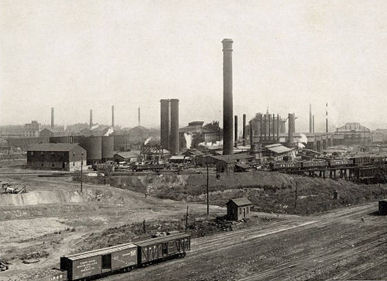

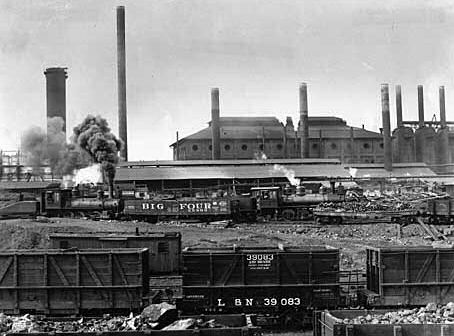

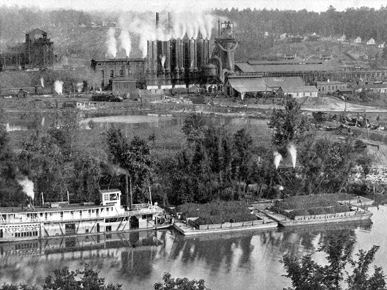

Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Co.

TCI&RR Co. furnace - Ensley AL

Sipsey Mine - Walker County, AL 1913

Banner Coal Mine - Pratt Consolidated Coal Co.

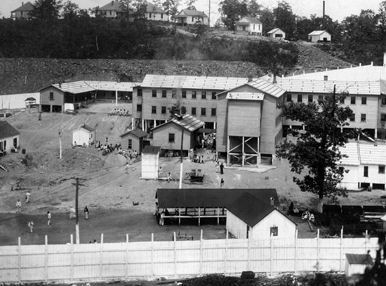

Pratt Company Mining Prison Camp

Prisoner Miners at Banner Mine

Central Iron & Coal Company's facility, Bibbville, AL

Sloss-Sheffield Steel & Iron Co. Bessie Mine - Jefferson Co.

Birmingham Coal Miners

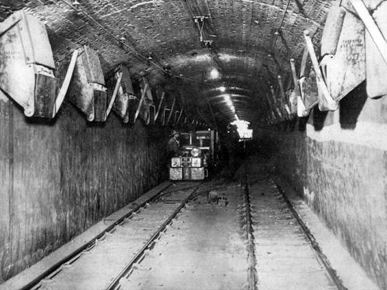

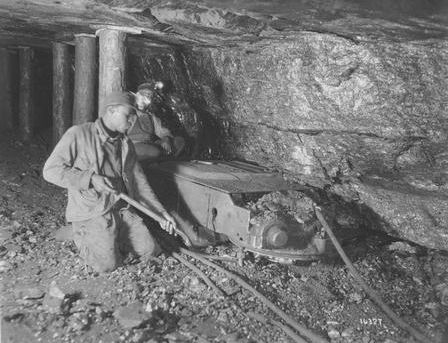

Long Wall Cutter - Peerless Cahaba Coal Co. - Straven, AL

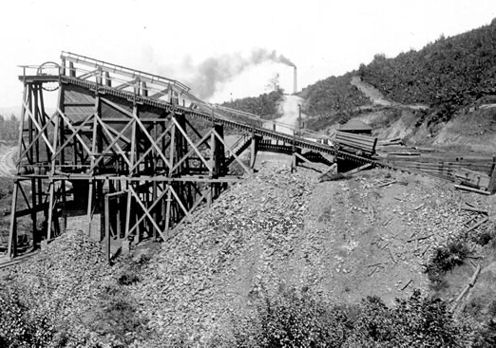

Blocton Cahaba Coal Co. - Coleanor, AL

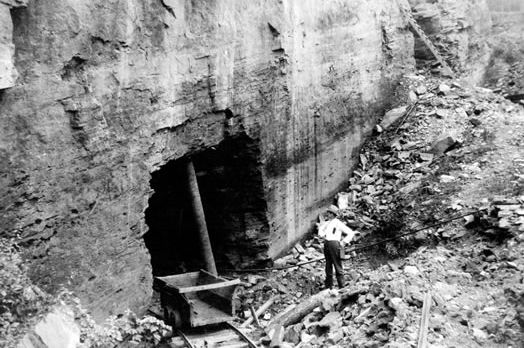

Ruffner Mine #1 Big Seam - Jefferson County AL

Central Iron & Coal Co. Mine - Giles AL

Tennessee Coal Co Alice Mine - Jefferson County AL

Iron mining - Irondale, Jefferson County, Alabama