CANADIAN MINES

The Klondike Gold Rush was sparked in 1896 by the discovery of gold at Rabbit Creek (also called Bonanza), a tributary of the Klondike River. Miners had been slowly filtering into the Yukon interior through the Chilkoot pass and began fanning out in the area as early as the 1880s. Some of them even stayed through harsh Yukon winters to hold onto their claims. Others partnered up with First Nations women who were well adapted and experienced in surviving the rigors of frontier life. George Washington Carmack was an example. The Carmacks, along with Kate’s brother Skookum Jim and her nephew, Tagish Charlie, were the first to uncover rich placer deposits at Rabbit Creek. They were advised to check out the creek by a fellow prospector named Robert Henderson who passed through the area and prospected in an adjacent creek. News of the Carmacks’ discovery of gold at Rabbit Creek eventually spread to outlying mining camps nestled within the Yukon Valley. Miners soon showed up at the Bonanza, Eldorado, and Hunter Creeks to stake their claims. This was just the beginning of a mass exodus of prospectors from America up to the Yukon with the dream of striking it rich.

Many of the stampeders who made their way to the Yukon were ill prepared for the long journey. Virtually overnight, a number of outfitting companies helped to furbish stampeders for the trip, selling them a variety of goods including food, warm clothing, mining and camping equipment, and transportation. Even in hard economic times, money was freed up to finance the expeditions of over 100,000 stampeders. The city of Seattle, the closest American outpost to the Yukon, profited greatly from outfitting miners. In order to pass into the Yukon, the Northwest Mounted Police demanded each miner carry up to a year’s supply of goods. This was equal to about one ton of goods per person.

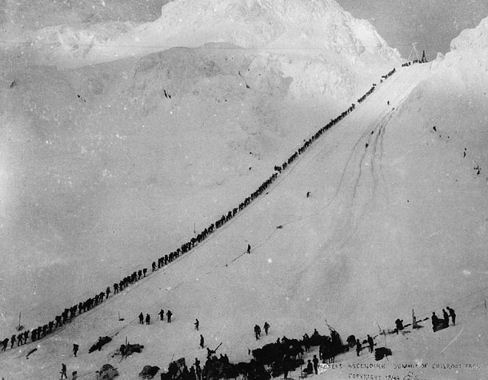

Those with extra money were fortunate enough to travel up to the Yukon aboard steam ships departing from San Francisco and Seattle. The less fortunate were forced to make the journey entirely by foot and with the assistance of pack animals. Different routes were marked out for the journey with the two most clearly established routes based from the closest salt water ports situated 600 miles from the gold fields at Skagway along the White Pass Trail or from Dyea along the Chilkoot Pass Trail. Dyea and Skagway quickly grew into boomtowns that catered to the needs of miners. Both routes, about 30 miles long, were treacherous to cross and posed many dangers. The Chilkoot Pass was steep and hazardous. Many stampeders had to make the journey over the pass in the dead of winter. Rising approximately 1,000 feet in the last half-mile, over 1,500 steps had to be cut out of the mountainside glacier of the Chilkoot Pass. Known as the "Golden Staircase,” the stepped incline was still too steep for packhorses to traverse, so stampeders had to cache their goods up the mountain, meaning it took many subsequent trips to move one ton of equipment and supplies over the pass. This task proved too arduous for some, who ultimately abandoned their equipment. Others simply resigned from completing the journey and turned back. Traveling the Chilkoot Pass during the summer still proved to be very difficult.

Those who took to the White Pass Trail did not fare much better. Conditions on the narrow, steep, and slick mountain trail were even more treacherous. Approximately 3,000 pack animals, mostly horses, died trying to cross the pass, and it was therefore renamed Dead Horse Pass. Alternative routes included the Copper River Trail, the Teslin Trail by the Stikine River and Teslin Lake, the all-Canadian Ashcroft route known as the Cariboo Wagon Route, and Edmonton trails.

A good number of stampeders ended up on the shores of Bennet Lake during the winter and were forced to set up temporary tent cities as they waited for the ice on the river to thaw. From here they had to build boats manually by scavenging for timber and whipsawing the timber into planks for the final 500-mile leg upriver to Dawson City. There were about 7,000 different types of boats and rafts made. On average, the journey upriver to Dawson City took three weeks. About 20,000 of the 30,000 stampeders to complete the journey to the Yukon had arrived in Dawson City by the summer of 1898. However, by this time, prospectors who had arrived the year prior had already staked out the best claims along the Klondike River.

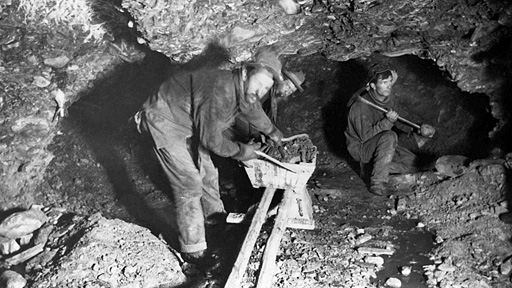

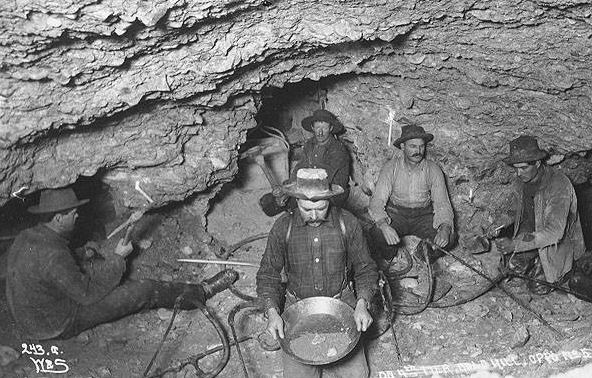

The work required of prospectors to extract the gold from their claims along the Klondike River was intensive. Gold was not always easily found at the surface; it was sometimes located 10 feet or more underground. In the winter months, miners had to dig through layers of permafrost by lighting fires to heat the ground in order to thaw it out. Most digging had to been carried out during the summer months.

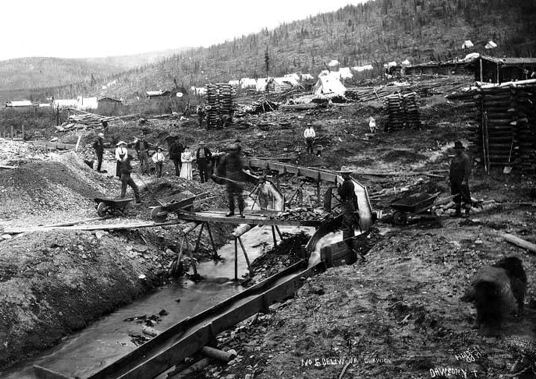

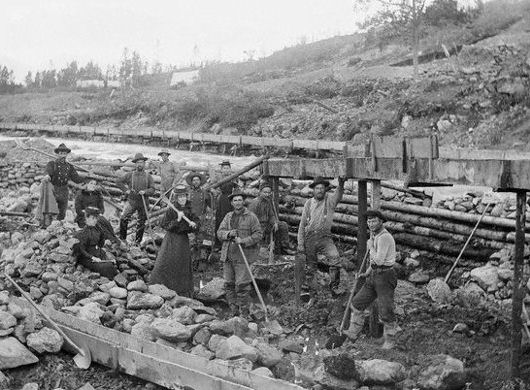

Panning was a common way to sample the potential of a possible claim. Panning only yielded a small amount of gold at any one time. To extract large amounts of gold involved processing larger amounts of gravel. This was accomplished with the use of sluices. Sluices were built directly in or near streambeds so the gravel could be easily separated from the gold. The gravel was removed from the bottom and banks of the streambeds and placed in the sluices for processing. The drawback was that the streams remained frozen for up to nine months of the year, denying prospectors both flowing water and access to the gravel in the streambed.

Many of the stampeders who made the difficult journey up to the Yukon, some taking up to two years to get there, never did strike it rich. Altogether, miners spent about $50 million dollars trying to reach the Klondike. This amount ended up equalling the actual value of gold extracted in the five years following Carmack’s first discovery of the gold placer deposits at Rabbit Creek.

Sudbury

Originally named Sainte-Anne-des-Pins ("St. Anne of the Pines"), the community started as a small lumber camp in McKim township. During construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway in 1883, blasting and excavation revealed high concentrations of nickel-copper ore at Murray Mine on the edge of the Sudbury Basin. Earlier, in 1856, provincial land surveyor Albert Salter had located magnetic anomalies in the area that were strongly suggestive of mineral deposits, although his discovery aroused little attention because the area was remote. However, the railway construction made large-scale mining development in the area economically feasible for the first time.

The community was renamed for Sudbury, Suffolk in England, the hometown of CPR commissioner James Worthington's wife. The original settlement at Sudbury was not strongly associated with the mines, but served primarily as a transportation hub and a commercial centre for the separate mining camps and farming communities that surrounded it—miners only began residing in Sudbury itself later on, as improvements to the area's transportation network made it possible for workers to live in one community and work in another. Sudbury was incorporated as a town in 1893, and its first mayor was Stephen Fournier. Thomas Edison visited the Sudbury area as a prospector in 1901, and is credited with the original discovery of the ore body at Falconbridge.

Through the decades that followed, Sudbury's economy went through boom and bust cycles as world demand for nickel rose and fell. Demand was high during the First World War, when Sudbury-mined nickel was used extensively in the manufacture of artillery in Sheffield, England. It bottomed out when the war ended, and then rose again in the mid-1920s as peacetime uses for nickel began to develop. The town was reincorporated as a city in 1930.

Demand for nickel in the 1930s was such that after an early slowdown, the city recovered from the Great Depression much more quickly than almost any other city in North America, and was for much of that decade the fastest-growing city in all of Canada and one of the wealthiest - to the point that most of the city's social problems in the Depression era were caused not by unemployment, but by the fact that the city was growing so rapidly that it had difficulty keeping up with all of its new infrastructure demands, such as housing, roads, sewers and public transit. Between 1936 and 1941, the city was in fact ordered into receivership by the Ontario Municipal Board. Notably, the city's former mayor William Marr Brodie had himself been appointed to the Ontario Municipal Board in 1934; in their book Sudbury: Rail Town to Regional Capital, historians C. M. Wallace and Ashley Thomson theorize that Brodie lobbied for the receivership order to protect the city from excessive debts and expenditures, even though several other cities in Ontario which were not placed into receivership were technically in much worse financial shape.

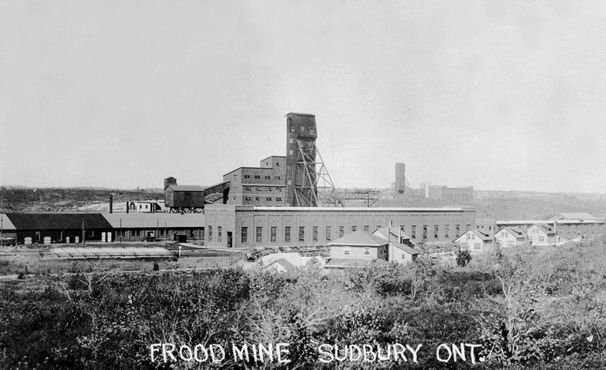

Another brief economic slowdown hit the city in 1937, although the city's fortunes rose again during the Second World War. The Frood Mine alone accounted for 40 per cent of all the nickel used in Allied artillery production during the war. After the end of that war, however, Sudbury was in a good position to supply nickel to the United States government when it decided to stockpile non-Soviet supplies during the Cold War. In 1940, Sudbury became the first city in Canada to install parking meters.

Robert Carlin, a prominent Mine Mill organizer, was elected to the Legislative Assembly of Ontario in 1943 as the city's first-ever Co-operative Commonwealth Federation representative, although he was later expelled by the party for not sufficiently denouncing the purported and vastly overstated prominence of Communists in the union.

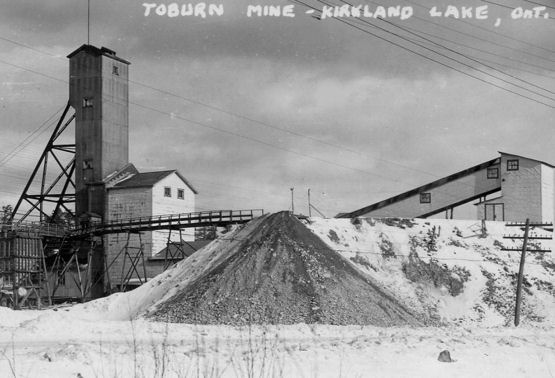

The Cobalt Rush was instrumental in opening northern Ontario for mineral exploration. Prospectors fanned out from Cobalt, and soon caused the nearby Porcupine Gold Rush in 1909, and the Kirkland Lake Gold Rush of 1912. Much of the settlement in northern Ontario outside the Clay Belt owes its existence indirectly to the Cobalt Rush

In the late 19th century the Ontario government started a program to establish settlements in the Clay Belt, a band of rich soil running north of Lake Temiskaming. The government wanted to open what was then known as "New Ontario", after it had been merged into the province from formerly Northwest Territories land. At the time, direct settlement to farms was still fairly widespread, and the towns of New Liskeard and Haileybury formed in the 1890s as the hubs of this activity.

The settlements generated some commercial interest in building a railway from North Bay to New Liskeard, but these plans ended when the rate of settlement dwindled at the turn of the 20th century. In 1902 the government decided to take over the project and started development of the T&NO, contracting out construction to a wide array of companies. By the summer of 1903 the line was about 100 miles long and was approaching Haileybury.

James McKinley and Ernest Darragh were contractors supplying ties to the T&NO, working north of the Montreal River, about 5 miles south of Haileybury. On the banks of Long Lake (one of many lakes in northern Ontario with this name) they found a number of pebbles bearing small metal flakes, and on 15 August 1903 they staked a claim and sent several samples to an assayer in Montreal. These proved to be disappointing, but a number of further samples they sent in in the fall returned 12% silver.

Fred LaRose, a blacksmith also working on the railway, had set up small cabin at the north end of Long Lake, near the Mile 103 post of the line. About two weeks after McKinley and Darragh, LaRose found similar rocks. LaRose noted "One evening I found a float, a piece as big as my hand, with little sharp points all over it. I say nothing but come back and the next night I take pick and look for the vein. The second evening I found it." LaRose had no idea what the metal was, he thought it might be copper, but staked a claim anywWhen the contract ran out, LaRose started on his way back to his home in Hull, Quebec. On the way he stopped at the Matabanick Hotel in Haileybury, where he showed his samples to the owner, Arthur Ferland. He then started on his trip, and on the way stopped in Mattawa where he visited a store owned by locals Noah Timmins and his brother Henry. Larose showed the samples to Noah before moving on to Hull. Henry was in Montreal at the time, so Noah cabled him, telling him about LaRose's find. Henry immediately set out for Hull, meeting LaRose and offering him $3,500 for half of the claim. Some time later a story developed that he found a vein when he threw a hammer at a fox walking by his tent.

Shortly thereafer, Ferland had another guest stay at the Matabanick, Thomas W. Gibson, the Director of the Ontario Bureau of Mines. Gibson identified the mineral in the samples as niccolite, a nickel-bearing mineral, which was intensly interesting to the Bureau after finding the deposits in Sudbury in 1883. Gibson sent the samples to Willet Green Miller, a professor at Queen's University and Ontario's first Provincial Geologist. With the samples Gibson included a note which stated that "If the deposit is of any considerable size it will be a valuable one on account of the high percentage of nickel which this mineral contains. I think it will be almost worth your while to pay a visit to the locality before navigation closes."

In October another railway contractor, Tom Herbert, came across an open vein of silver on the east side of Long Lake. He told Ferland about it that night, and the two set out for the site the next day. Due to a loophole in the Mining Act, surface veins allowed prospectors to stake up to 320 acres, rather than the typical 40. Ferland formed a syndicate with four railway engineers, purchased Herbert's claim for $5,000, and jointly staked a total of 846 acres.

Meanwhile, Miller had examined the samples Gibson sent him, and was disappointed to find that only the surface had any niccolite, the interior being mostly cobalt of little commercial value. He nevertheless sent the samples for further analysis, which returned a report stating they had 19% silver within. Miller soon set out for Long Lake, arriving in November 1903.

Miller visited a number of the veins that had been discovered, reporting that at the base of the LaRose vein he observed "lumps of weathered ore weighing from 10 to 50 pounds carrying a high percentage of silver", while the Little Silver Vein had "pieces of native silver as big as stove lids and cannon balls" and that "loose silver is common in immediate proximity to the vein; every depression in the rock on the top of the hill contains much free silver. The earth occupying these depressions is deemed by the owners of sufficient value to sack and ship for treatment".

William Trethewey arrived in the spring of 1904 and set out prospecting the area. On his second day he found a vein, and staked it with another prospector, Alex Longwell. Immediately thereafter he found a second vein, staking it for himself, while Longwell went off to stake another of his own. All three would later develop into major mines, the Trethewey, Coniagas and Buffalo. Millar had returned to the area to continue work, and posted a sign alongside the railway tracks which read "Cobalt Station T. & N.O. Railway". Still, there was relatively little work being done commercially, and nothing like a "rush" started.

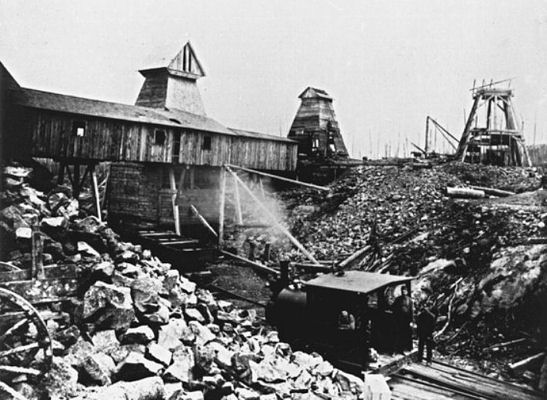

When travel re-opened in the spring of 1905 word was out that there was silver at Cobalt Station. Prospectors and developers started pouring into the campsight, and by the end of the year there were 16 operating mines that had shipped $1,366,000 worth of ore. The next year another $2,000,000 worth of ore was shipped, but the obvious surface viens were mined out. To continue production, trenches were dug in criss-cross patterns hoping to cut through a vein. The Nipissing Mine introduced the use of high-pressure water to simply wash off all of the topsoil, and by 1913 Long Lake, now known as Cobalt Lake was "tainted or yellow green, and is opaque". The lake was later drained, both to clear out the brakish water as well as to expose further veins.

Although one of the richest veins was known as early as 1904, development was slowed by disagreements among the shareholders. These were finally worked out and mining the "Lawson Vein" started in 1908. Once mining was underway it became clear that the vein was incredibly large, as much as 10,000 tons of processed silver, making it the largest single find in the world to this day. It is better known today as the "Silver Sidewalk".The rush reached its peak in 1911, shipping 31,507,791 ounces of silver. The town had grown considerably, and had a population of between 10,000 and 15,000.

World War I made labour hard to come by, and by 1917 most of the mines had closed due to a lack of men to work them. Instead, the small number of workers available were put to work using new extraction methods to work the tailings, which required far fewer people to keep in operation. At the end of the war Cobalt had a population of about 7,000. In 1918, in spite of the problems, 10,000 tons of silver were shipped.

As the best viens were mined out the cost of extracting silver from the Cobalt area made it increasingly unprofitable. By the 1922 many of the smaller mines were closed, when the Great Fire of 1922 swept through the area. Most of the viens ended less than 300 feet (91 m) below the surface, limiting the total amount of silver in the area. The stock market crash of 1929 led to a major devaluation in metal prices, rendering even the deeper mines unprofitable. The LaRose closed in 1930, and by 1932 only the Nipissing Mine and a few smaller operations were still working. All of these were closed by 1937.

In the World War II era and immediately thereafter, cobalt became a valuable mineral in its own right, and a number of operations opened to process the tailings again, this time for the cobalt. Increasing silver values and better mining processes started to make the area profitable, and the 1950s saw a brief resugence of mining. Most of these closed by the 1970s, and the few remaining ones by the early 1980s.

Prospectors Climbing Chilkoot Pass

Gold Hill, Dawson, Yukon Territory

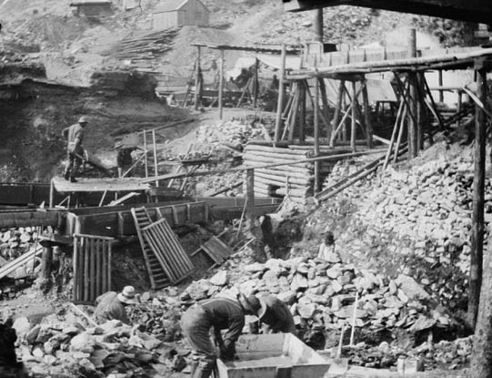

No.9 Anvil White Star Mining Co. - Dawson, Yukon Territory - 1902

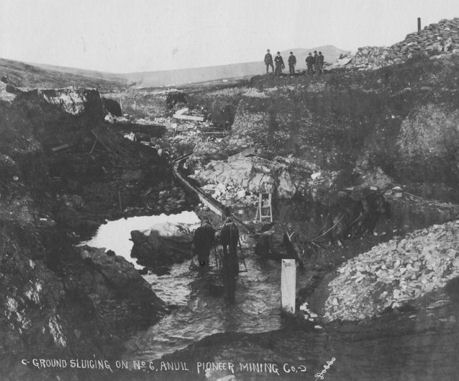

No. 6 Anvil Pioneer Mining Co.- Dawson, Yukon Territory - 1902

No.19 Below Discovery - Miller Creek, Yukon Territory

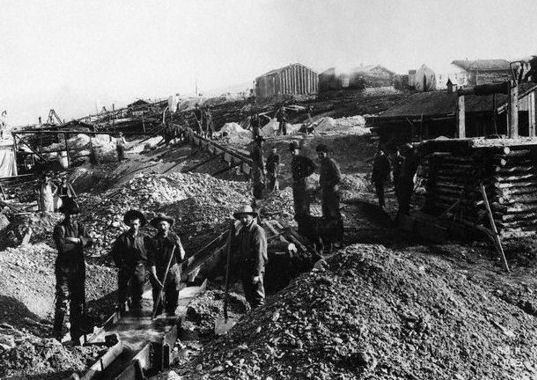

Unidenfied Klondike Gold Mining Operation

Mining gold-bearing gravel - Klondike

Unidenfied Klondike Gold Mining Operation

Digging in the perma-frost - Dawson, Yukon Territory

Claim No. 44, Bonanza Creek, Yukon Territory 1901

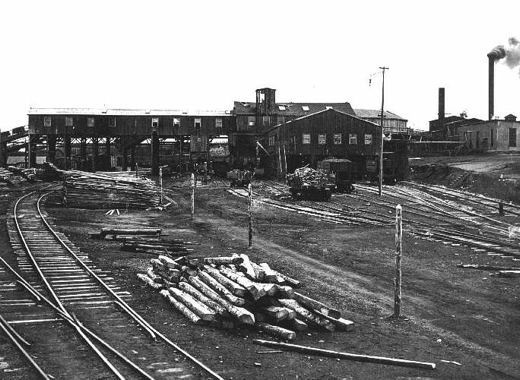

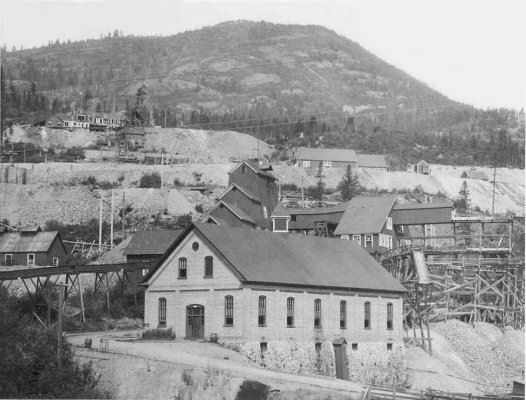

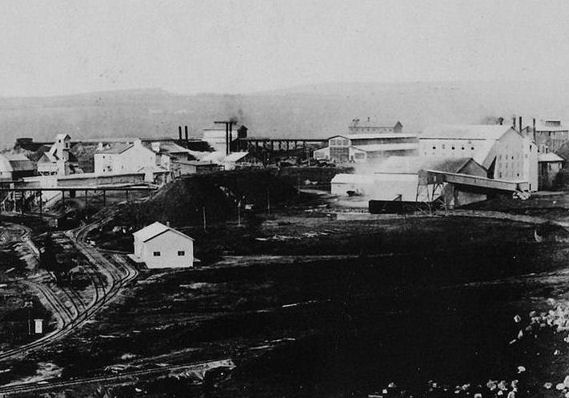

Dominion Nickel Mine, Sudbury, Ontario

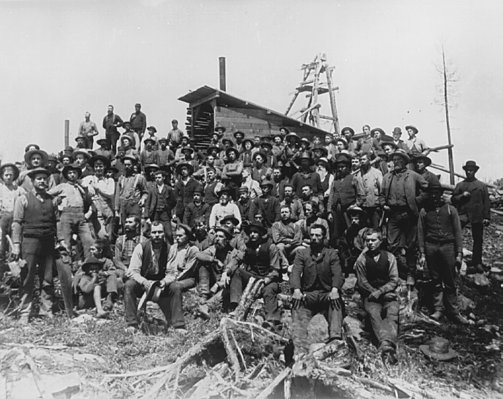

Miners in Sudbury District, Ontario, 1890s

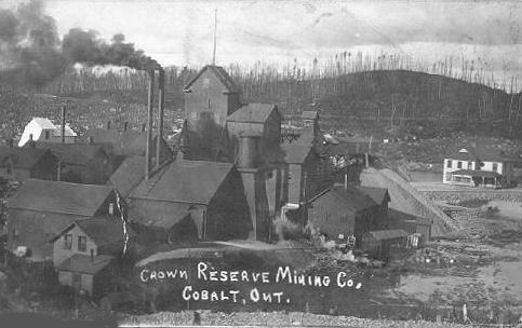

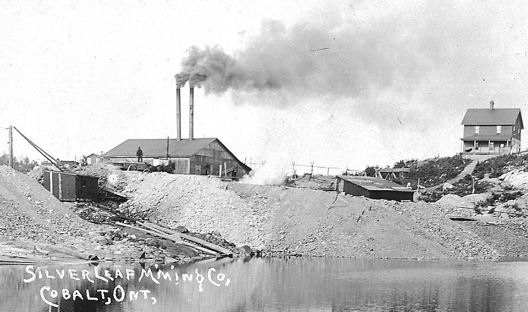

Silver Leaf Mine - Cobalt, Ontario

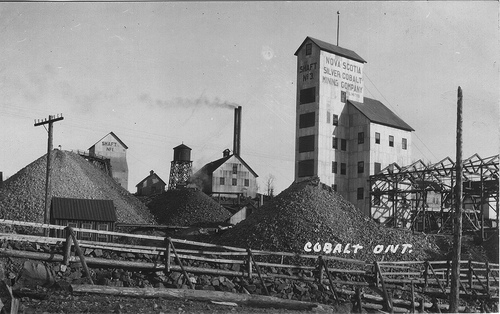

Nova Scotia Silver Cobalt Mining Co. - Cobalt, Ontario

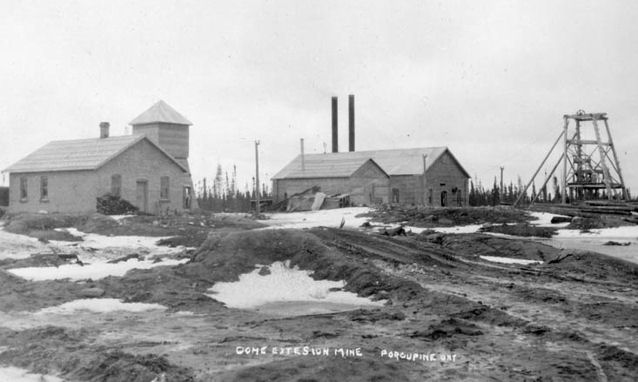

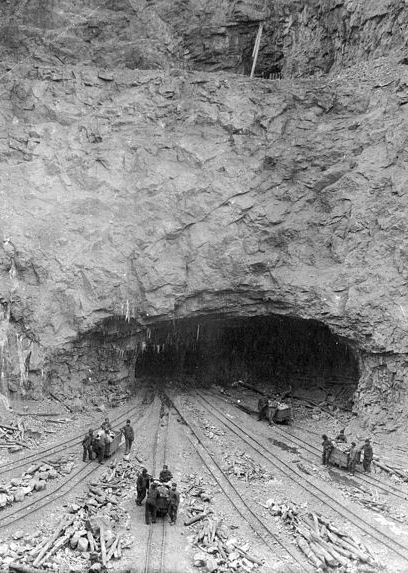

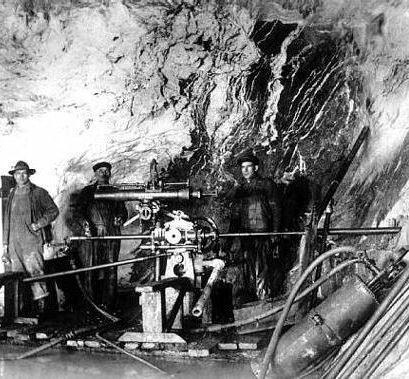

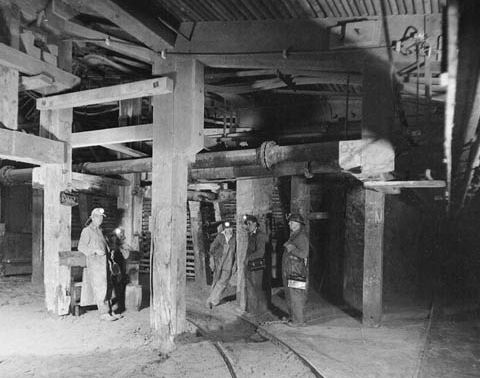

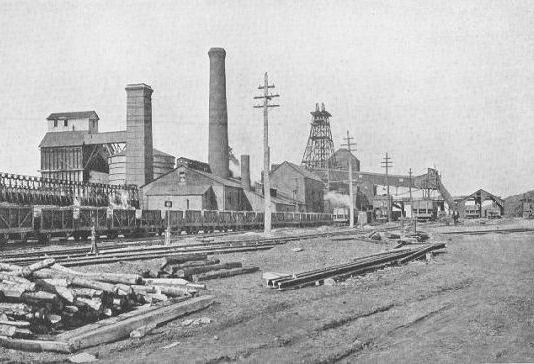

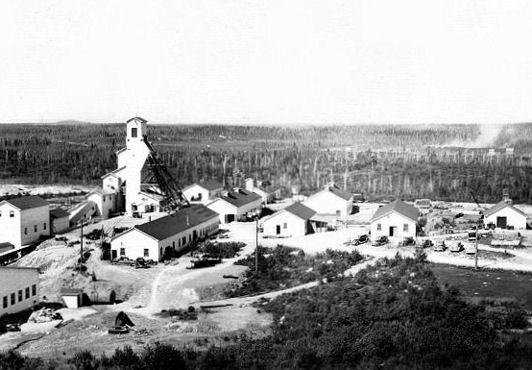

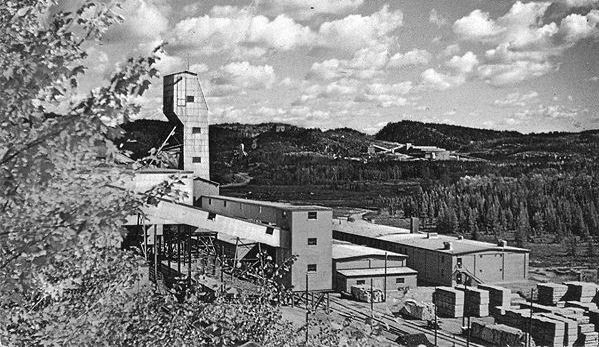

Dome Extension Mine - Porcupine, Ontario

Dome Extension Mine - Porcupine, Ontario

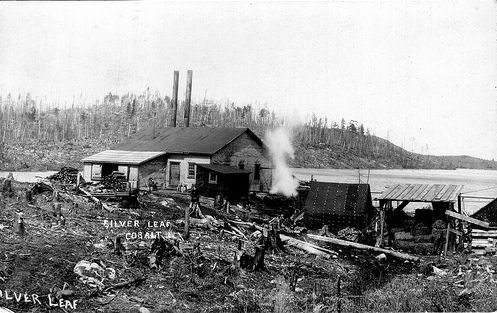

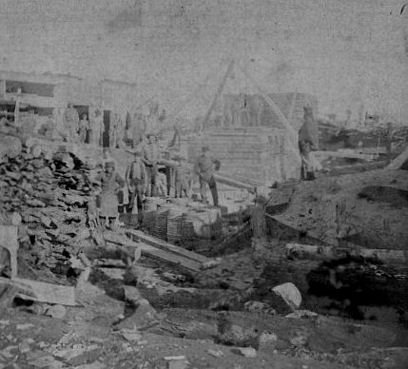

Silver Miners - Cobalt, Ontario

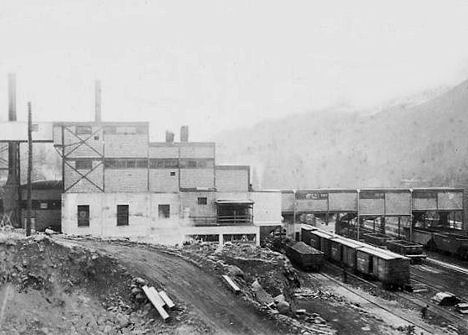

Hollinger Mine, Timmins, Tisdale Township, Cochrane District, Ontario 1911

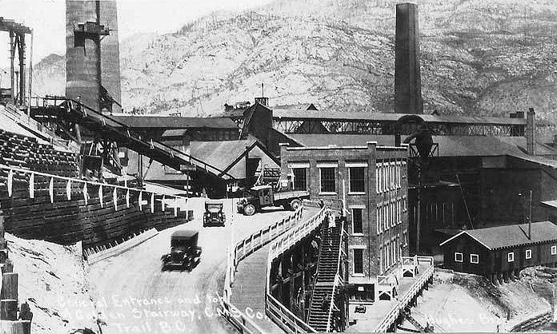

Hollinger Mine, Timmins, Tisdale Township, Cochrane District, Ontario

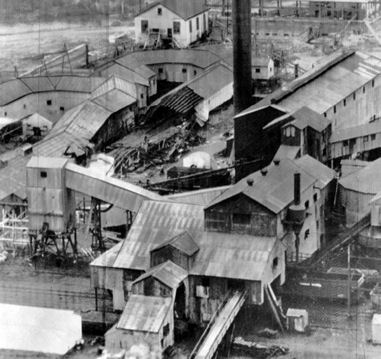

Hollinger Mine, Timmins, Tisdale Township, Cochrane Dist., Ont. 1918

Hollinger Mine, Timmins, Ontario

Hollinger Mine, Timmins, Tisdale Township, Cochrane District, Ontario

Silanco Mine - Cobalt, Ontario

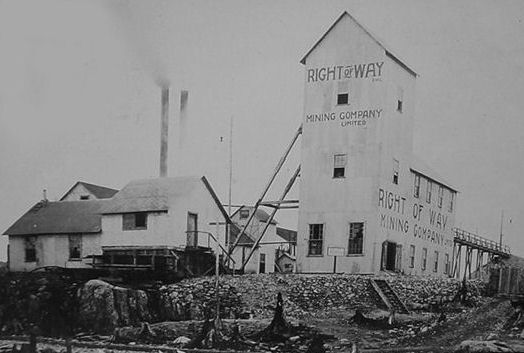

Right of Way Mining Co. - Cobalt, Ontario

Unidentified Silver Mine - Cobalt, Ontario

Creighton Mine - Sudbury, Ontario

Gold Hill, Yukon Territory, ca. 1898

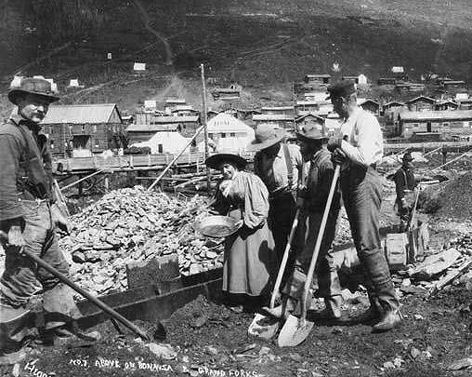

No. 7 above Bonanza & Grand Forks - Dawson, Yukon Territory

Hydraulic mining - Lovett Gulch, Bonanza Creek, Yukon Terr. 1907

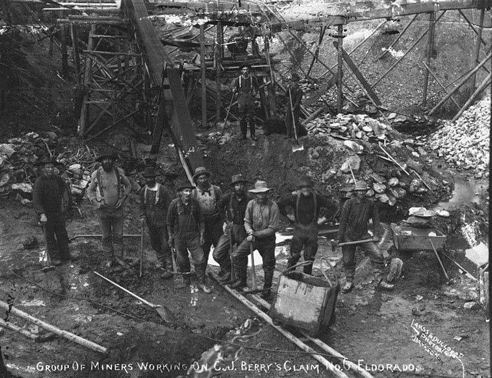

Berry's Claim No. 6 - Eldorado Creek, Dawson, Yukon Territory 1900

Dominion Creek, Yukon Territory 1898

Skookum Hill, Yukon Territory 1898

No. 17 Eldorado Claim - Yukon Territory 1898

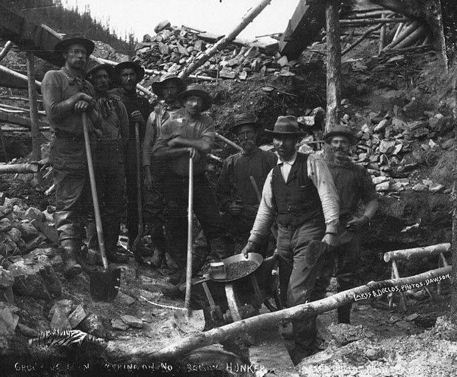

Hunker Creek near Dawson, Yukon Territory 1900

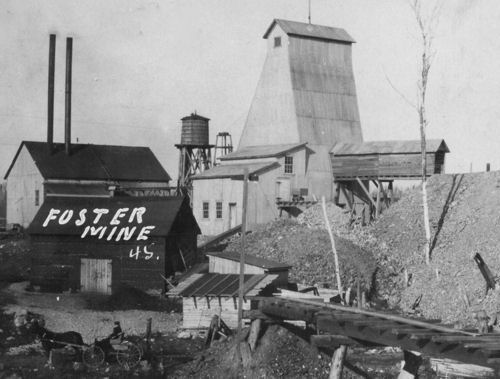

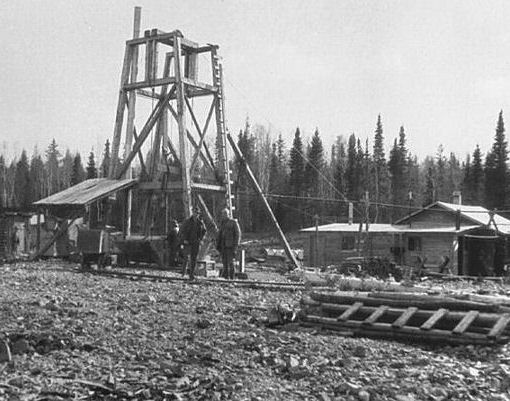

Foster Mine - Porcupine, Ontario

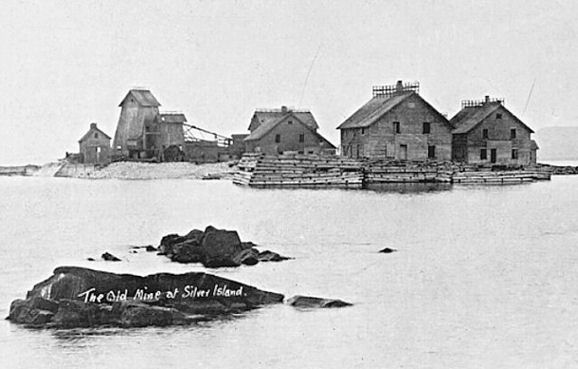

Silver Islet refers to both a small rocky island and a small community located at the tip of the Sibley Peninsula in northwestern Ontario, Canada. It was the first silver mine in Ontario. A rich vein of pure silver was discovered on this small island in 1868 by the Montreal Mining Company. At that time, the island was approximately 90 feet and only about 3 feet above the waters of Lake Superior. In 1870, Montreal Mining Company sold their land and patents to Alexander H. Sibley’s Silver Islet Mining Company for $225,000. Alexander Sibley of Detroit headed the company and he appointed W.B. Frue as his partner and mine captain. In 1870, the site was developed by the Silver Islet Mining Company which built wooden breakwaters around the island to hold back the lake's waves and increased the island's area substantially with crushed rock. The islet was expanded to over 10 times its original size and a small mining town was built up on the shore nearby.

After most of the purest ore from the original site had been removed, a second vein was discovered in 1878. By 1883, most of the highest quality silver had been extracted and the price of silver had declined. The final straw came when a shipment of coal did not arrive before the end of the shipping season. The pumps holding back the waters of the lake stopped and in early 1884 the islet's mine shafts, which had reached a depth of 384 metres, were flooded. They would never be de-watered, and the mine's underground operations would never be reopened.

Silver Islet Mine, Silver Islet, Sibley Township, Thunder Bay District, Ontario

Silver Islet Mine, Silver Islet

Silver Islet Mine, Silver Islet

Silver Islet Mine, Silver Islet

Nova Scotia has been a long-time source of coal for use domestically and abroad. The Nova Scotia coal deposits are divided into the Sydney, Cumberland, and Pictou Coalfields. Canada has one-sixth of all the coal reserves in the world, almost as much as the entire continent of Asia, and second only to the United States.

The Sydney Coalfield, the largest and most valuable in Nova Scotia, is situated on the north eastern coast of Cape Breton Island, extending from Mira Bay on the south to Cape Dauphin on the north, a distance of thirty miles, and has a general dip northeast under the Atlantic. The field embraces the mining communities of Morien, Birch Grove, Reserve, Dominion, Glace Bay, New Waterford, and Sydney Mines. The city of Sydney is situated about midway between the northern and southern extremities of the field and on the western fringe of the productive coal measures.

Coal was first mined in the Sydney Coalfield by the French military from outcroppings in 1685. Later, in 1720, organized mining was conducted in the Blockhouse Seam in the Morien Basin. For the next 100 years, outcrop mining was done in various parts of the field. In 1825, the General Mining Association was formed and, two years later, an effort was made to do systematic mining in the Sydney Mines and New Waterford Districts. In 1849, the Crown conveyed its interests in the minerals of the Province to the Government of Nova Scotia. In 1857 the General Mining Association, which until then held under sub-lease all the mineral areas of the Province, in consideration of certain concessions and privileges, surrendered its holdings to the Government of Nova Scotia, reserving, however, for its own operation certain areas in Cumberland, Pictou and Cape Breton Counties, totaling 30 square miles. Shortly thereafter, several mining companies were formed and mines were opened in the Glace Bay District. In l90l the General Mining Association sold out its interests in Sydney Mines to the Nova Scotia Steel & Coal Company.

In the Cape Breton Coalfield, the Glace Bay District contributes 46 percent, the New Waterford District 37 percent and Sydney Mines 17 percent of the coal produced in the area. Due to submarine conditions, it is not possible to accurately determine the tonnage yet recoverable from this field. Already approximately 219,000,000 tons has been extracted and it is estimated that 257 million tons of economically recoverable coal is still available within proven areas of the Dominion Coal Company, Limited and 23.5 million tons within the area of the Old Sydney Collieries, of a quality equal to that being mined at the present time, and that the recoverable coal, without regard to quality or economic feasibility, within the limits of five miles seawards from the shore is approximately 947 million tons, sufficient to last for nearly 200 years at the present rate of production.

The Cumberland Coalfield consists of a basin-shaped strip of coal stretching from Chignecto Bay in the west where the seams dip under the Bay of Fundy, in a South-Easterly direction to the Town of Springhill, a distance of 25 miles. The basin is approximately 12 miles wide, lying between the Cobequid Highlands in the North, East

and South, and is entirely located in Cumberland County. The coal areas are located mainly in the Joggins River and Hebert areas in the North and at Springhill near the Eastern end of the basin; this latter area being the most important in the field.

In the Cumberland Coalfield, the coal areas at Springhill, in common with those in other districts in Nova Scotia, were originally leased in 1825 to the General Mining Association by the Duke of York. When the lease was nullified in 1857, having in 1849 released to the Government of Nova Scotia all its interests in the minerals of the province, the General Mining Association, as compensation for loss of rights was permitted to select and retain certain limited areas. Among these were four square miles of coal lands at Springhill, lack of transportation facilities prevented coal being mined other than at the outcrops by farmers for their own use, until 1870. With the prospect of rail transportation becoming available, a Company known as the Springhill Mining Company was formed. This Company leased from the Government certain areas outside the limits of the General Mining Association holdings, and systematic coal mining on a moderate scale began.

In 1878 the workings had reached the boundary of the General Mining Association property and in the following year this area was transferred through the Crown from the G. M. A. to the Springhill Mining Company. A few years later the Springhill and Parrsboro Coal and Railway Company was organized.

These two companies were merged in 1884 under the title of the Cumberland Railway and Coal Company, which began mining on a much larger scale. In 1910 the Dominion Coal Company Limited absorbed the Cumberland Railway and Coal Company. Springhill was the site of three mine disasters in 1891, 1956 and 1958, which killed 125, 39 and 74 miners respectively.

It is reported that coal was first discovered in Pictou County, at Stellarton, in 1798 and that in 1807 the first license to mine coal was issued to John McKay. In 1817, Adam Carr obtained a lease from the Crown to mine and export coal. In 1825, through the prerogative of the Crown, the then Duke of York obtained a lease of all the mineral rights in Nova Scotia, with the exception of a few small areas already leased or held under grants.. Messrs. Rundell, Bridge & Rundell of London, received a transfer of the Duke's lease which they subsequently transferred to a Company known as the General Mining Association.

In 1827, the General Mining Association came to Pictou County and sank the Store Pits on the Foord Seam. By 1829 they had completed a six mile long railway, which connected the mines to the wharf at Abercrombie. It is worth noting that the first steam locomotive on the American continent ran on this line.

In 1849, the mineral rights were vested in the Province of Nova Scotia and in 1857 the original lease of the General Mining Association was nullified. As partial compensation for loss of their original rights, the General Mining Association was permitted to select and retain certain limited areas, amongst these were four square miles surrounding the town of Stellarton.

It had been the intention of the General Mining Association to work the iron deposits as well as the coal. A blast furnace was erected at the Albion Mines and iron ore was sent in from the Springville District. These efforts at iron smelting proved unsuccessful and the project was soon abandoned.

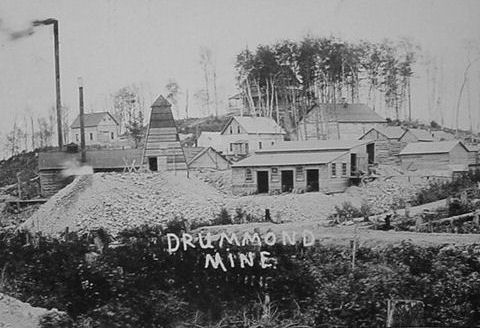

The Acadia Coal Company was organized in 1864, securing leases adjoining those of the General Mining Association, They sank the Thorn Pit on the MacGregor Seam in 1866. This pit was soon abandoned as the Acadia seam, which was more commercially promising, was discovered about two miles to the westward at a location that is now the site of Westville. The working of this seam was successful and led to the formation of the Inter-colonial Coal Company, which acquired leases to the south of the Acadia properties and sank the Drummond Slope to work the Acadia Seam.

In 1871 the Nova Scotia Coal Company was formed, leasing coal lands to the north of the Acadia areas. They sank the Black Diamond Slope, also on the Acadia Seam. This latter area was sold to the Nova Scotia Steel & Coal Company, Limited, in 1889. They sold it to the Acadia Coal Company in 1893. In 1872 the Vale Coal & Iron Manufacturing Company was organized. They purchased leases of coal lands at Thorburn and began operations in the MacBean Seam.

In the same year, 1872, the Halifax Coal Company was formed, purchasing all the mining rights of the General Mining Association in Pictou County. In 1886, the Acadia Coal Company, the Halifax Coal Company and the Vale Iron & Manufacturing Company all merged under the title of the Acadia Coal Company, Limited.

In 1900, the Nova Scotia Steel & Coal Company Limited, after securing the leases of coal lands between New Glasgow and Thorburn, sank the Marsh Shaft on the MacKay Seam. In 1919, the Acadia Coal Company was purchased by the Nova Scotia Steel & Coal Company and thus came into the merger of the British Empire Steel Corporation in 1921. The Pictou Coal Field today is largely depleted, although certain sections of the field still contain some pockets of mineable coal. The coal field lies about 9 miles inland from the shore of Northumberland Strait and just beyond the head of the tidal water of the East River, at which point we find the Town of Stellarton.

The area occupied by the productive coal is comparatively small as the coal belt extends, roughly, only ten miles in an East and West direction, with a minimum width of three miles. The Town of New Glasgow is situated on the northern boundary of the coal field and lies approximately half-way between its eastern and western extremities. New Glasgow has been the commercial and industrial center of northern Nova Scotia, known best for its ship building industry.

The history of coal mining on Cape Breton began over 250 years ago. In the early 1700's, coal was needed in Louisbourg for the French to construct its Fortress. Coal was extracted from exposed seams along the cliffs and in 1720 the first coal mine was officially opened at Cow Bay, or Port Morien as it is now known. In the 1800's, rows of company houses could be found at Morien, along with hundreds of miners.

During the period of 1784-1820, coal deposits were mined on a small scale by either the colonial government or through lease by private individuals. In 1826, Frederick, Duke of York, was granted sole right by the Crown to all coal resources of Nova Scotia. The Duke subleased these rights to a syndicate of British investors called the General Mining Association who then sunk shafts mainly at Sydney Mines. The Association built workshops, company houses, a foundry and a railroad to North Sydney.

In 1856, the General Mining Association surrendered its mining rights and the province invited independent operators to apply for leases and subleases. From 1858 to 1893, more than 30 coal mines were opened in the province, producing 700,000 tons in the last year.

In 1873, there were eight coal companies operating in Cape Breton. The miners were paid from 80 cents to a $1.50 per day and boys were paid 65 cents. The first large mine, the Hub Shaft of Glace Bay opened in 1861 and several other mines in Glace Bay and Sydney Mines opened within the next few years. In total, Glace Bay had 12 coal mines. In 1894, the government gave exclusive mining rights to an American syndicate, the Dominion Coal Company. By 1903, the Dominion Coal Company was producing 3,250,000 tons per year. By 1912, the company had 16 collieries in full operation and its production accounted for 40% of Canada's total output.

Francis Gray, an English mining engineer who had immigrated to Cape Breton, expressed it best by commenting "Take away the steel industry from Nova Scotia and what other manufacturing activity has the province to show as a reflex of the production of 7,000,000 tons of coal annually. The coal mined in Nova Scotia, has for generations, gone to provide the driving power for the industries of Quebec and Ontario." For almost a century, Nova Scotia has been exporting the raw material that provides the base of all modern industry.

"The Cape Breton Development Corporation, a federal Crown corporation, currently controls all leases on the Sydney Coal Field. This coal field, which contains the only metallurgical coal east of Alberta, is part of a large carboniferous basin stretching from Cape Breton Island some 100 kilometers north-east. Its leasehold is a small portion of the total coal field which extends only eight kilometers off-shore. Currently there are no large coal mines in operation.

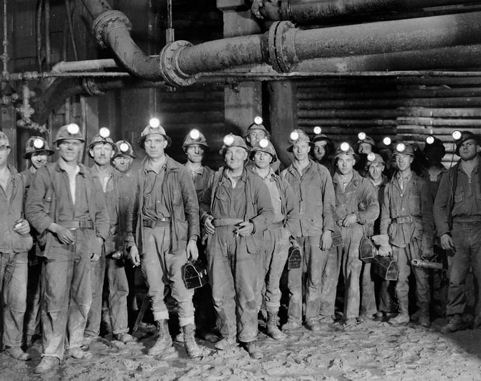

Cape Breton Coal Miner

Cape Breton Coal Miner

Cape Breton Coal Mine

Coal Mine - Inverness, Cape Breton

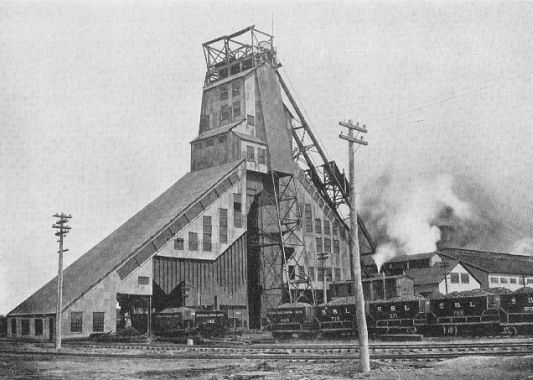

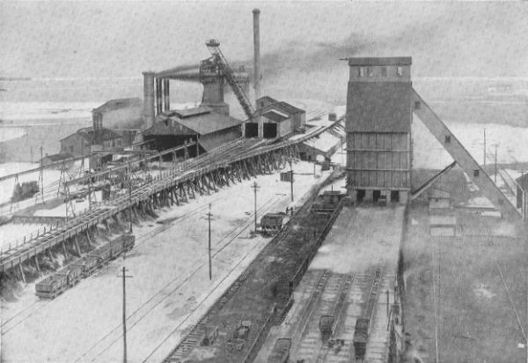

Dominion Coal Co. Dominion No. 2 Colliery - Glace Bay, NS

Drummond Coal Mine - Pictou County, NS

Princess Colliery of the Nova Scotia Steel and Coal Company - Sydney, NS

Nova Scotia Steel & Coal Company - Sydney Mines, NS

Draegermen - Stellarton, Nova Scotia

Coal Mine - Cape Breton

The presence of gold in the region that is now British Columbia is mentioned in old legends that, in part, led to its discovery. Gold was first formally discovered by non-indigenous people at Gold Harbour on the west coast of Moresby Island in the Queen Charlotte Islands, near the Haida village of Tasu on Mitchell Inlet, an arm of Gold Harbour (which is part of Tasu Sound). A brief gold rush - the Queen Charlottes Gold Rush - ensued in the following year, leading to the declaration of the Colony of the Queen Charlotte Islands to prevent the archipelago from being overrun by Americans and so claimed by the United States. The extent of the ore body proved superficial, and there are various stories of American prospecting parties harassed by the Haida people, who were still very numerous.

Gold discoveries are not reported in the journals of the early fur traders, and it became policy on the part of the fur companies to not advertise the presence of gold as the protection of the fur trade was the main corporate interest of their enterprise. Governor Etolin of Russian America expressly forbade news of gold discoveries as a serious crime against the state. Small quantities of gold were reported by traders in the 1830s and at some posts became current in local trading, though not common or in quantity. but Hudson's Bay Company policy, or the good judgement of the Chief Trader, kept news of such discoveries quiet until a large trove was brought into Fort Kamloops in 1856 by members of the nearby Tranquille tribe of the Secwepemc. When news of the find, and a large poke of gold dust brought to James Douglas, Chief Factor of the Columbia Department at Fort Victoria and also Governor of Vancouver Island, decided to ship it to San Francisco for smelting. Some historians have suggested he did so deliberately to spread news of the gold find so as to provoke a gold rush so as to force Britain's hand on the status of the British mainland north of the 49th parallel, which since the Oregon Treaty had remained unincorporated and had remained solely the domain of the fur company and its native clientele. American miners had been appearing more frequently on British soil and Douglas felt he had to take action.

News of the finds in what was then known as New Caledonia hit California at a time of economic depression, when the gold fields were depopulated and many miners were in San Francisco, where the news hit like wildfire and overloaded steamers full of men equipped with not much more than gold pans and the clothes on their back headed north, along with entrepreneurs of all kinds and others seeking to profit not from the mines, but from the miners. Victoria, until then a "sleepy English village" of a few hundred people, was transformed into a tent city of some 30,000 within weeks in the spring of 1858. After initial complaints of a "humbug" because high water levels prevented mining, thousands returned to California, only to be replaced by others as water levels dropped and mining began in earnest.

The first major find, and among the largest on the river, was at Hill's Bar about 15 kilometres south of Fort Yale, which had become the epicentre of the gold rush as it was at the head of river navigation and at the foot of the Fraser Canyon and its difficult trails and rich gold-bearing bars. Hill's Bar's first claim, known as the "Boatmen of San Francisco", worked the bar alongside Chief Kowpelst and his people, the Spuzzum tribe of the Nlaka'pamux, whose village was just north of Fort Yale. The mining population, split in thirds about evenly between Americans, Chinese, and a mix of Britons and Europeans who had been in California, many since the California Gold Rush ten years earlier. entered into conflict when two French miners violated a Nlaka'pamux girl near Lytton, then called "the Forks", and their beheaded bodies were seen floating down the river. In the ensuing unrest, known as the Fraser Canyon War, most of the mining population fled the Canyon for Spuzzum and Yale, and war parties composed of Americans, Germans, French and others (many who had been mercenaries in Nicaragua, or in service of France in Mexico), forayed up the canyon and made a peace with the Nlaka'pamux, though many were killed on both sides. News of the war had reached Victoria in the meantime and Governor Douglas was forced to take action to enforce British authority and sovereignty on the mainland and set out by steamer with Royal Marines and the newly-arrived first contingent of Royal Engineers for the gold fields. En route, the party stopped at Fort Langley, then still located at Derby, where Douglas declared the Colony of British Columbia and was sworn in as its first Governor, on August 1, 1858. Proceeding without much incident to Yale, where news of the governor's journey upriver had travelled in advance, the Governor and his troops were greeted by the war parties or "Companies" that had engaged in the war, flying the British flag and greeting the Governor with a formal welcome. Admonishing them that the colony had been established and the Queen's Law would prevail, the governor appointed officials who would later lead to a series of events known as McGowan's War over the course of the next winter. Also while at Yale, Douglas decreed the creation of subscriptions by which parties of men could pay for the right to construct a new route to the "Upper Fraser" via the Lakes Route, as a way around the dangers of the canyon trail and continued fears about the Nlaka'pamux. the "Upper Fraser" was the area of Lillooet and Fountain and several thousand miners had arrived in that region via overland routes through Oregon and Washington Territory, despite an injunction from Douglas that all access to the goldfields would be through Victoria only. Those who came by those routes, the busiest but war-ridden Okanagan Trail, also spread farther afield in the Interior, leading to gold discoveries further and further afield and a string of small and large gold rushes including what would become the largest and most famous, the Cariboo. Not for nothing that among the most common sobriquet used at the time for the new Mainland Colony was "the Gold Colonies".

By 1860, there were gold discoveries in the middle basin of the Quesnel River around Keithley Creek and Quesnel Forks, just below and west of Quesnel Lake. Exploration of the region intensified as news of the discoveries got out, and because of the distances and times involved in communications and travel in those times, moreover because of the remoteness of the country, the Cariboo Rush did not begin in earnest until 1862 after the discovery of Williams Creek in 1861 and the relocation of the focus of the rush to the creek valleys in the northern Cariboo Plateau forming the headwaters of the Willow River and the north slope of the basin of the Quesnel. The rush, though initially discovered by American-based parties, became notably Canadian, Maritimer and British in character, with those who became established in the Cariboo among the vanguard of the movement to join Canada as the 1860s progressed. Many Americans returned to the United States at the opening of the Civil War. Others went on to the Fort Colville, Idaho, and Colorado Gold Rush. Some went elsewhere in the Intermontane West, including other parts of British Columbia, in addition to those who had come and gone during the advent and wane of the Cariboo rush. To preserve British authority and retain control over the traffic of gold out of the region, the Governor commissioned the building of the Cariboo Road, a.k.a. the Queen's Highway, and a route from Lillooet and also established the Gold Escort, although that government agency never proved viable and private expressmen dominated the shipment of goods and mail into the gold fields, and gold out of it (see Francis Jones Barnard and B.X. Express). Among other events associated with the Cariboo Gold Rush was the Chilcotin War of 1864, provoked by an attempt to build a wagon road from Bute Inlet to Cariboo via the Homathko River. In addition to the gold rush's capital and destination of the Cariboo Road Barkerville, dozens of small towns and mining camps sprang up across the rainy, swampy hills of the Cariboo, some such as Bullion and Antler Creek attaining mining fame in their own right. The Cariboo gold fields have remained active to this day, and have also yielded other boomtowns, such as Wells, a one-time company town town of 3,000 in the 1920s just a few kilometres west of Barkerville, which today is a museum town, and one of the larger deep-rock mines in the Cariboo mining district. The city of Quesnel, remained important after the wane of the rush as the jumping-off point for other goldfields discovered yet farther and farther north in the Omineca and Peace River Country to the north of Fort George (today's city of Prince George), then only a small fur post and Indian reserve.

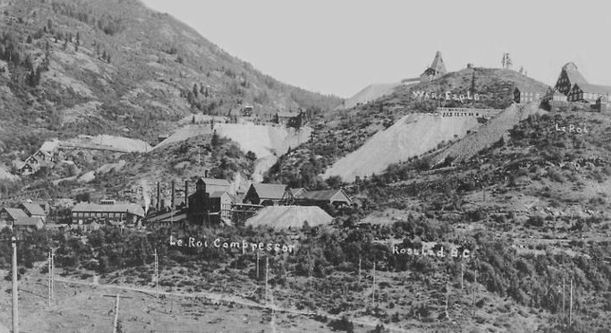

Le Roi Compressor, War Eagle, and Le Roi mines - Rossland, British Columbia

LeRoi Mine - Rossland , BC

The Similkameen Gold Rush, also known as the Blackfoot Gold Rush, was a minor gold rush in the Similkameen Country of the Southern Interior of British Columbia, Canada, in 1860. The Similkameen Rush was one of a flurry of small rushes peripheral to the Fraser Canyon Gold Rush, which had drawn tens of thousands of prospectors to the new colony in 1858-1859, among the others being Rock Creek Gold Rush and Big Bend.

Discovery of gold on the upper Similkameen River in 1860 led to the establishment of the town of Blackfoot, also known as Blackfoot Flat and adjoined by a neighbouring settlement, Blackwood Flat, seven miles southwest of what is now Princeton near the site of the later mining town-cum-ghost town Allenby. The population of the town in the fall of 1860 was approximately 100, a mix of white and Chinese miners. By the summer of 1861 its population was reported as only about 50. High water made mining operations on the river difficult, but bench claims, above the water-mark, proved successful and one shaft was sunk in an effort to find hard-rock deposits. Blackfoot and Blackwood Flat contained 40 houses, including a store and other services.

The Rock Creek Gold Rush was a gold rush in the Boundary Country region of the Colony of British Columbia (now part of a Canadian province). The rush was touched off in 1859 when two US soldiers were driven across the border to escape pursuing Indians and chanced on gold only three miles into British territory, on the banks of the Kettle River where it is met by Rock Creek, and both streams turn east to where in times since developed the city of Grand Forks (so-named because of its location at the confluence of the Kettle and Granby). The first claim was filed by an Adam Beam (or Beame) in 1860, and the rush was on, composed mostly of Americans and some Chinese, all of whom had come overland from other workings, either at Colville or Oregon or all the way from California.

At its peak, an estimated 5,000 men were in the area, where the new town of Rock Creek had grown to a population of about 300, when trouble broke out between American and Chinese miners, and the efforts of the colony's Gold Commissioner Peter O'Reilly to end the disturbances, as well as to collect the Queen's mining licenses, resulted in him being driven from the mining camp by a hail of stones in what has become known to history as the Rock Creek War, as it was dubbed at the time by the Victoria newspapers.

O'Reilly fled to Victoria and reported to Governor Douglas, who after a trip to Lillooet via Port Douglas and the Lakes Route, went on into Princeton (which on the way he named "Princetown", in honour of the Prince of Wales, visiting distant Canada at the time; also during this visit to Lillooet the Governor approved its residents' new name for the former Cayoosh Flat). Douglas, accompanied by W.G. Cox, who was to be new commissioner, and Arthur Bushby, most well known for being clerk and companion to Judge Begbie, proceeded to Rock Creek. Once he arrived, he admonished a meeting of 200 miners and told them if they didn't follow his orders, he would come back with 500 marines. As he had at Yale two seasons earlier, he also instructed them the Chinese had the same rights to the gold workings as any other, and further molestation of them would not be permitted. At the end of the meeting, he insisted on shaking each man's hand and looking them in the eye as they left the tent as a way of ingraining his personal expectations on each of them.

The workings on Rock Creek did not last many years, and when the Colville Gold Rush began soon after, many Americans went on to the new diggings and Rock Creek's gold-mining heyday became a memory. The troubles of this goldfield were a critical demonstration of Douglas' awareness communication between the Coast and the Interior was vital to the security of the colony, underscoring his contracting of Edgar Dewdney to build a trail from Fort Hope to the East Kootenay (where similar troubles had broken out). The purpose of the Dewdney Trail was to prevent draining the Interior's gold and other resources to the United States, as well as to be able to deploy troops should trouble break out and either Indian war or outright annexationist uprising should arise in areas where access to and through the United States was far easier than from the Coast.

The Stikine Gold Rush was a minor but important gold rush in the Stikine Country of northwestern British Columbia. The rush's discoverer was Alexander "Buck" Choquette, who staked a claim at Choquette Bar in 1861, just downstream from the confluence of the Stikine and Anuk Rivers. at approximately. Choquette was the son-in-law of the Tlingit chief Chief Shakes, who presided over the region at the mouth of the river, the site of the former Fort Stikine and today's city of Wrangell, Alaska, and had also explored the Nass and several other rivers. Once news of the find reached the various other goldfields in British Columbia, the lower Stikine in the area of Choquette's find was inundated with prospectors and the river itself busy with steamboat traffic, served by vessels who abandoned the moribund Fraser routes.

Not much gold was found on the Stikine, but the flurry of activity prompted Governor James Douglas of the Colonies of Vancouver Island and British Columbia to declare, in 1862, British ownership over the region in the form of the Stickeen Territories, which extended north from the northern frontier of British Columbia at the Nass and Finlay Rivers to the 62nd Parallel. The Stickeen Territories were a year later merged with British Columbia, except for the portion north of the 60th Parallel, which reverted to the North-Western Territory from which the Territories had been taken upon their creation. Mineral exploration of the region continued in the wake of the rush, with the much-larger Cassiar Gold Rush, north of Telegraph Creek, discovered in 1870 by Harry McDame.

With the success of the smelter, the small town of Trail grew. On June 14th, 1901 the City of Trail was incorporated. The townspeople celebrated the historic event and what seemed to be a promising future on July 1st. In 1906 the smelter, the War Eagle, Centre Star, and St. Eugene mines, along with the Rossland Power Company were amalgamated to form the Consolidated Mining and Smelting Company of Canada Limited (CM&S). Under the direction of Walter H. Aldridge, the CM&S solidified the smelter operations.

Gradually improvements to the smelter increased production and employment in Trail. As World War I approached, an end of an era was near. In 1911 Aldridge left Trail for Thompson, Nevada, and in 1914 Heinze died in New York, in financial ruin. The CM&S purchased the Sullivan Mine in Kimberley in 1910, and the smelter began to rely primarily on lead/zinc ores for its livelihood.

World War I increased the demand for lead and zinc and the CM&S realized the need to develop a better means to treat zinc ores. Ralph W. Diamond was hired to develop a process to treat the rich lead/zinc ores of the Sullivan Mine. His research led to a breakthrough in treating zinc ore with the development of the zinc electrolytic refining process. In 1917 labor unrest developed at the smelter and consummated with a general strike lasting 36 days.

In the 1920s, under the direction of S.G. Blaylock, the CM&S expanded its Trail operations and increased its production of lead and zinc. With expansion of the smelter operations, the city prospered. The population increased as the demand for workers at the smelter grew.

In the 1930s the CM&S constructed a chemical fertilizer plant in Warfield to reduce sulphur dioxide emissions in the valley. Zinc and lead production steadily increased. Exploration for new mines in the Northwest Territories led the CM&S to become pioneers in aviation exploration, which led to the Columbia Gardens Airport being constructed. A dairy was also established by the CM&S in Warfield, which provided milk to the townspeople.

During World War II, production at the smelter was increased to assist with the war effort. The West Kootenay Power Plants on the Kootenay River were expanded and CM&S participated in the development of the atom bomb. On May 8, 1945, Blaylock died and Diamond assumed management of the smelter operations. With the end of World War II, another era in Trail's history had come to an end.

Consolidated Mining & Smelting Co. - Trail, BC

Elk River Mine - Fernie BC

Hydraulic Mining - Atlin, B.C.

Placer Mining - Pine Creek, British Columbia

The discovery of the first lead deposit occurred in 1686 in the Abitibi-Témiscamingue region, when Chevalier de Troyes investigated traces of the metal on the eastern shore of Lac Témiscamingue, previously noted by the inhabitants of Fort Témiscamingue, guided by Amerindians. The discovery, however, was forgotten for the next 200 years, until it was rediscovered by E.V. Wright in the 1850s and mined for lead, zinc and silver in the 1890s.

The first true mines did not open in Québec until the 1840s, when several major mineral deposits were identified, mainly in the south. Following the discovery of a famous gold nugget in the Beauce region by Clothilde Gilbert, completely by chance, Québec experienced its first gold rush, and by 1847 the first alluvial gold operation had opened. This was also the period when Québec declared its ownership of all underground mineral resources and, by introducing various legislative and administrative measures, acted to control and promote exploration and mining in Québec.

A major copper and sulphur mine opened in the Eastern Townships around 1860, which was also when asbestos was first mined.

In 1906, Alphonse Olier and Auguste Renault discovered the first gold deposit in the Rouyn-Noranda region, on the shores of Lac Fortune. Despite their discovery, the area only became a centre for mining following the staking of claims and the discovery of a copper and gold deposit at the northern end of Lac Tremoy by Edmund Horne, a prospector from Nova Scotia, in 1922. The early 1920s was when mining really became established in Québec. The growth of the mining industry, which coincided with large-scale industrial expansion elsewhere, quickly made Québec an important source of minerals for the most highly industrialized areas of North America.

After World War II, growth was concentrated mainly in the asbestos sector, and later in copper and iron. From 1922 to 1945 and 1955 to 1965, several discoveries were made and several new mines opened. The first "mining boom" of the early 20th century resulted from the discovery of surface deposits by prospectors using traditional methods, while the second resulted from the discovery of hidden deposits using aerial detection methods. For example, this technique was used to discover deposits of zinc and copper sulphates in the Matagami and Joutel regions, around the same time the Chapais-Chibougamau sector was being developed.

In 1890, the discovery of gold and copper ores on the face of Red Mountain, by Joe Moris and Joe Bourgeois was the single most important event in the history of Trail and the Trail/Rossland area, and triggered a series of events that led to the first settlement in Trail. Claims were registered at the Nelson Mine Recorder's Office, giving deputy mining recorder Eugene S. Topping the inside scoop on the potential for the Rossland mining boom. Topping and his friend, Frank Hanna, promptly purchased 139ha/343ac at the outflow of Trail Creek. The pair made a big profit selling town lots and, in 1895, land was made available for the construction of the first smelter. The City of Trail was incorporated in 1901.

Under British Columbia law only four of the five claims could be recorded at the Nelson Mine Recorder's Office. The deputy mining recorder, Eugene Sayre Topping, agreed to pay the recording fees for the claims in return for ownership of the fifth claim. Topping and his friend, Frank Hanna, then purchased 343 acres at the mouth of Trail Creek on the Columbia River, hoping the claims on the neighbouring Red Mountain would be developed into paying mines, and make them wealthy through the sale of town lots. Their hopes became a reality in 1895. The Rossland mines proved to be very rich in gold/copper ore and the lots in the Trail Creek townsite sold briskly.In 1895 Topping provided land to F.A. Heinze of Butte, Montana to build a smelter to treat the Rossland ores. The smelter was purchased by the C.P.R. in 1898 and expanded its production to include lead ores. Despite the difficult economic times, the smelter succeeded.

Nickleplate Mine - Rossland, BC

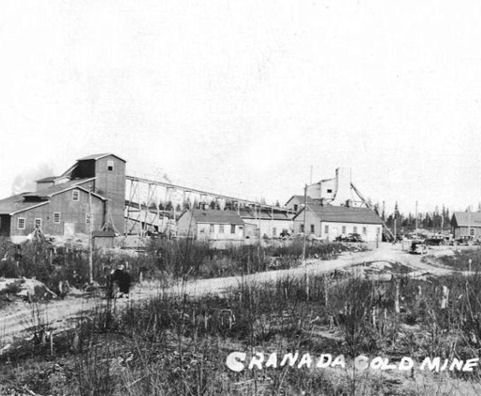

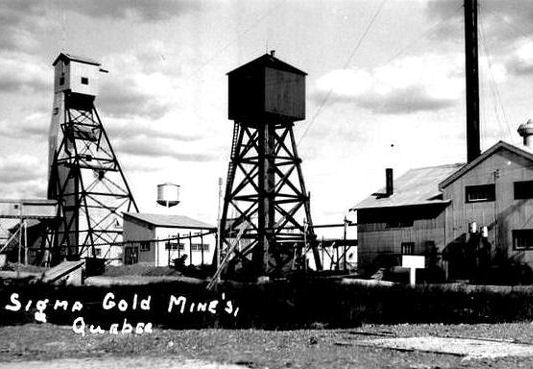

Gold mining - Granada Shaft, Rouyn, Quebec

Eustis Mine - Eustis, Quebec

No. 1 shaft & smelter Noranda Mines, Quebec

Granada Gold Mine - Rouyn Noranda, Quebec

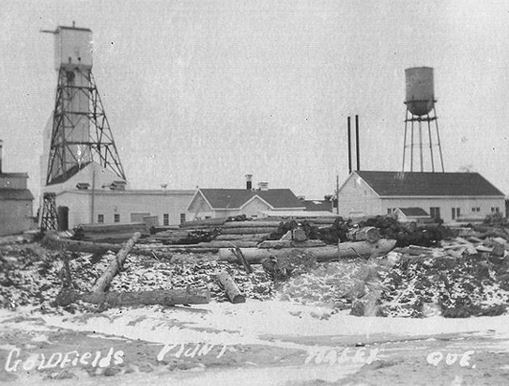

Goldfields Mine & Mill - Haley Malartic, Abitibi, Quebec

Central Cadillac Gold Mine - Cadillac, Quebec

North Star Phosphate Mine - Du Lieire River, Ottawa Co. Quebec

Amiante Asbestos Mine - Quebec

Blatte Gold Mine, DuParque, Quebec

Large-scale mining began in Manitoba in 1930 when a copper-zinc mine at Flin Flon on the Manitoba-Saskatchewan border went into production. Since then, Thompson, Lynn Lake, The Pas and Leaf Rapids have become major mining centres for copper, zinc, nickel and precious metals. Nickel from the huge Thompson nickel belt, where production began in 1960, accounts for nearly 40% of the value of Manitoba's mineral production, with copper and zinc each accounting for 18%.

Lynn Lake was founded in 1950, when a deposit of nickel ore was discovered. The nickel mine was developed, and soon after, gold was also discovered. Most of Lynn Lake's 208 houses and commercial buildings were moved from Sherridon, Manitoba, over cat train trails. The houses and commercial buildings were moved by digging out the foundation, loading them on the tricycle winter freighting sleigh pulled by Linn tractors and caterpillar crawlers. The buildings once loaded were the last sleigh on the cat trains which were usually 4-5 sleighs long. The Linn Tractors were used to move the town of Sherridon, Manitoba to Lynn Lake, Manitoba in the 1950s.

After a rich vein of copper ore had been nearly depleted in Sherridon, the company sent out prospectors to find another strike. Around 1945, the expeditions were successful when one of the world's largest nickel strikes was found near the soon to be established Lynn Lake. Most of the people of Sherridon moved to Lynn Lake when housing was completed.

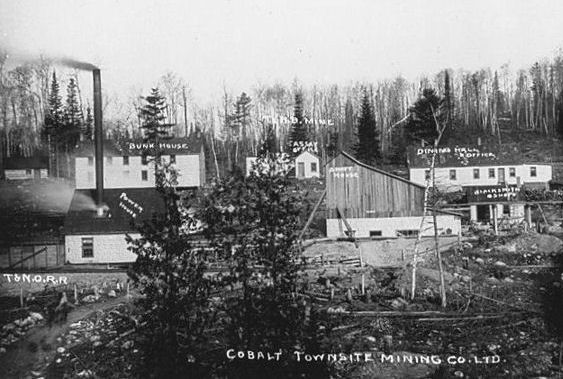

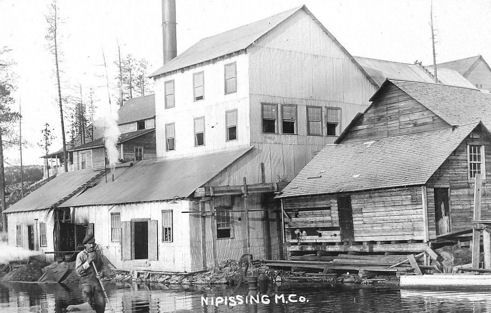

Nipissing Mining Co. - Cobalt, Ontario

The Cobalt Silver Rush started in 1903 when huge veins of silver were discovered by workers on the Temiskaming and Northern Ontario Railway (T&NO) near the Mile 103 post. By 1905 a full-scale silver rush was underway, and the town of Cobalt, Ontario sprang up to serve as its hub. By 1908 Cobalt produced 9% of the world's silver, and in 1911 produced 31,507,791 ounces of silver. However, the good ore ran out fairly rapidly, and most of the mines were closed by the 1930s. There were several small revivals over the years, notably in World War II and again in the 1950s, but both petered out and today there is no active mining in the area. In total, the Cobalt area mines produced 460 million ounces of silver.

.

Levack Mine - Sudbury, Ontario