MICHIGAN IRON MINES

There are three iron ranges in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, these are the Gogebic, Marquette and Menominee Ranges. The Gogebic was the last of the three great iron ore fields opened in the Upper Peninsula and northern Wisconsin. Beginning in 1848 with Dr. A. Randall, federal and state geologists had mapped the ore formations almost perfectly long before any ore was mined. One geologist, Raphael Pumpelly, on the basis of his studies in 1871, picked out lands for purchase, which years later became the sites of the wealthy Newport and Geneva Mines. The first mine to go into production was the Colby. In 1884 it shipped 1,022 tons of ore in railroad flat cars to Milwaukee. By 1890 more than thirty mines had shipped ore.

The Gogebic Iron Range extends for 80 miles from Lake Namekagon, Wisconsin, in the west, to Lake Gogebic in Michigan, in the west. Nathaniel D. Moore uncovered ore deposits in the Penokee Gap near Bessemer in 1872, but it was not until 1884 that the first iron ore shipment was made. The Gogebic Range area experienced an initial speculative boom in the mid-1880s, and saw recurring booms and busts from 1884 to 1967.

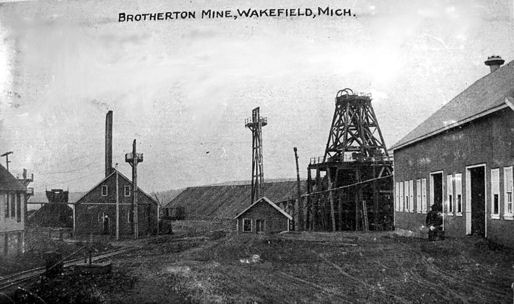

The area of greatest production was in the Ironwood, Michigan/Hurley, Wisconsin area. Some important producers in this area included the Norrie mine, Aurora mine, Ashland mine, Newport mine, Bonnie mine, Davis mine, Geneva mine and Pabst mine in Ironwood. The Bessemer/Ramsay/Wakefield area had the Yale mine, Ramsay mine, Anvil/Palms mine, Sunday Lake mine, Castile mine, Brotherton mine, Wakefield mine, Mikado mine, Tilden mine, Colby mine, Asteroid mine, Plymouth mine and other smaller producers.

For decades in the late 19th century and into the 1920s, the Gogebic was one of the nation’s chief sources of iron. Iron from the Gogebic Range helped to fuel the industrial boom in the Midwest during these years. Mining was winding down in 1930s with mines beginning to close, amid a national economy also suffering from the Great Depression. The result was widespread economic devastation in the Gogebic Range.

Credit for the discovery of iron is given to Richard Langford, a trapper and hunter, who claimed to have seen red ore outcropping from the roots of an overturned tree south of the present city of Bessemer in 1879 or 1880. Langford presented samples of ore to Captain N. D. Moore who formed a mining company and began extensive exploratory work. By 1884, this ore location, known as the Colby Mine, began to produce commercial iron ore. In May, 1882, iron was discovered near Wakefield by George A. Fay, who had been prospecting between Ramsey and Lake Gogebic in 1881 and 1882, and the discovery became the famous Sunday Lake Mine. During that same year, A. L. Norrie began exploring land which was later known as the Norrie Mine in the city of Ironwood. The Norrie formed the nucleus of the large group of mines which later was operated by the Oliver Mining Company under the collective title of the Norrie-Aurora Mines.

The early explorers and prospectors on the Gogebic Range experienced the particular hardships of a land devoid of roads or even passable trails. Supplies had to be packed overland from Ontonagon or were brought by boat from Ontonagon to Ashland to the mouths of the Montreal and Black rivers. However, soon after the opening of the range for mining, the railroad made its initial entrance. The Milwaukee, Lake Shore and Western Railroad had begun a line that was to run from Milwaukee to Ontonagon, and by 1883 the railroad had reached Watersmeet, a few miles across the Wisconsin line into Michigan. With the fabulous riches of the Gogebic Range becoming more well-known, the company diverted its attention and extended the railway line into the new mining district during the summer of 1884. The first ore from the range came out of the Colby, and 1,022 tons were loaded onto flat cars in October of 1884, sent to Milwaukee, and then transshipped by barge to Erie, Pennsylvania. By 1910, three separate railway lines served the Gogebic Range, and approximately four million tons of iron ore were being shipped annually.

The Marquette Iron Range was the first Michigan iron range to be discovered and developed. The Marquette Range had been of interest to geologists since the early 1840s when Michigan's first State Geologist, Dr. Douglas Houghton, conducted a systematic scientific analysis and exploration of Michigan's Upper Peninsula. He published his findings in a lengthy report, detailing the locations of minerals in the Lake Superior area. Although he was not aware of the quantity of iron ore deposits in the area, Houghton did state that iron deposits were to be found on or near the south shore of the lake. Houghton's findings were substantiated and enlarged by the activities of William A. Burt, a United States Deputy Surveyor. Burt, in attempting to establish the east-west line between townships 47 North and 48 North, approximately one mile south of Teal Lake, noted strange variations in his magnetic compass needle. When using Burt's own invention, the solar compass, no variations were observed. Searching for the cause of this disturbance, the surveying party discovered deposits of iron ore, or hematite. In 1845, the search for iron ore began in earnest, and the first major discovery was made near the present site of Negaunee. The men of the search party formed the Jackson Mining Company on July 23, 1845, and iron mining in Michigan officially began. A furnace producing wrought iron from iron ore was erected on the Carp River, and it was there that the first metallic iron was made. The first blast furnace, built near the Jackson Mine, went into operation in April of 1849.

On July 7, 1852, the Marquette Iron Company shipped six barrels of ore to New Castle, Pennsylvania, the first shipment of Lake Superior ore via the lakes. However, shipping was constantly hampered by the rapids on the St. Mary's River at Sault Ste. Marie. Governor Stevens T. Mason had proposed a canal around this natural obstacle as early as 1837; however, no action was taken until 1852 when Congress officially authorized the construction of the vitally important canal. Initial work began June 4, 1853, and the canal was completed in April of 1855, thus removing one of the major deterrents to successful mining in the Lake Superior region. The development of roads and railroads in the Marquette Range also spurred mining activity and speculation.

Until 1864, the Jackson, the Cleveland, and the Lake Superior companies were the only shippers of iron in the district. The Civil War increased the need for Lake Superior iron, and the volume of shipments began a steady increase, with additional mines opening on the range toward the end of the Civil War. In 1861, the output for the Marquette Range was 120,000 tons; by 1868, annual figures had reached a half million tons; and, by 1873, the range produced over one million tons of ore, a figure that steadily increased through the turn of the 20th century. Capitalists from Cleveland played a key role in the development of the Marquette Iron Range, and the Cleveland-Cliffs Iron Company had acquired a controlling interest on the Range by 1890.

The last of the three Michigan iron ranges is the Menominee Range, one of six iron ore ranges adjacent to Lake Superior. About two-thirds of the iron ore produced in the United States comes from these ranges. Three of them are in Michigan and three in Minnesota Mesabi, Cuyuna and Vermillion). Part of the Menominee Iron Range extends into parts of northern Wisconsin. Of these six ranges, the Menominee is the second to have been developed, with the Marquette Range being the oldest.

The Menominee Range is situated mainly in the valley of the Menominee River, which lies on the boundary between the Upper Peninsula of Michigan and northern Wisconsin. The fact that iron was located here seems to have been known before the Civil War, but active mining dates back only to the 1870s.

In 1846 William A. Burt, the discoverer of the Marquette Iron Range, during his linear land survey, noted signs of iron ore in the Crystal Falls area. In 1849, federal geologist J.W. Foster was sent by Dr. Charles T. Jackson to investigate the reports of iron ore on the Menominee River. His reports listed significant finds of large beds of ore in Section 30, Township 40 North, Range 30 West, near Lake Antoine. Almost two years later, Foster was joined by J.D. Whitney and through a geological survey they together confirmed Burt’s report of the Crystal Falls district.

In 1866, two timber speculators from Menominee named Thomas and Bartley Breen located iron deposits near what is now Waucedah, Michigan. In 1972, this site became know as the Breen Mine and marked the first mining in the district. Soon after, Milwaukee Iron Company geologist and chemist Dr. Nelson P. Hulst began conducting extensive prospecting on the Breen property and a property that would later be known as the Vulcan Mine.

The Breen Mine was opened in 1872, and other locations opened soon afterward. But in the fall of 1873, the development of the mine was slowed when the effect of the national economic panic hit the Menominee Range and all preparation for mining ceased. By 1874, due to the prior prospecting of Hulst, it became evident that mining was a valuable venture and plans were back on track. However, they would be again delayed until 1877, when the Chicago and Northwestern Railway Company completed a railroad stretching from Quinnesec to Escanaba, easing shipping problems. During this year, the Breen and Vulcan mines shipped 10,405 tons of ore.

Active shipments, however, had to await construction of a branch of the Chicago and North Western Railroad from Powers, Michigan, on the main line of the Peninsular Division, which reached the district in 1877. The best outlet for the range was at Escanaba, on Little Bay De Noc of Lake Michigan, to which the North Western Railroad constructed a direct line. The Chicago, Milwaukee, and St. Paul Railroad also penetrated the region and shipped ore over the Escanaba and Lake Superior line until it reached a pooling agreement for shipment over the North Western. Numerous mines were opened at Vulcan, Norway, Iron Mountain, and Iron River, Michigan, and at Florence, Wisconsin.

By 1878, five mines were actively shipping from the Menominee Range, including the Breen, Cyclops, Norway, Quinnesec, and the Vulcan. By 1879, there were eight shippers moving over 200,000 tons of iron ore. Production at the Menominee Range continued to increase in the following years, and by 1882 it passed the one million mark in shipment. Total more than one and a half million tons were mined in the first five years and in the sixth year its production exceeded a million tons, an amount which it had taken the Marquette Range more than twenty years to equal

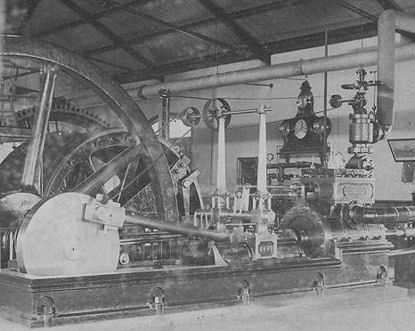

The best known producer was the Chapin Mine at Iron Mountain, which produced nearly 26 million tons of iron ore from its opening in 1879 to its closing in 1934. The Chapin mine is home to the largest steam-driven pumping engine in the United States. The Chapin Mine Pumping Engine (Cornish Pump) was patterned after the ones used in Cornwall in the deep tin and copper mines. Edwin Reynolds, chief engineer for the E.P. Allis Company (now the Allis-Chalmers Co.) of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, designed the steam engine in 1890. The engine's high pressure cylinder has a 50-inch bore, and the low pressure cylinder is 100 inches in diameter. The flywheel is 40 feet in diameter, weighs 160 tons, and had an average speed of only 10 revolutions per minute. The drive shaft to the flywheel is 24 inches in diameter. The engine itself rises 54 feet above the floor of the room. The designers estimate the weight to be 725 tons over all.

The pumping equipment utilized a reciprocating motion to a line of steel rods extending 1,500 feet down into the mine, with eight pumps attached at intervals of 170 to 192 feet along the rods. Each of the pumps forced the water to the next higher pump and finally out to the surface of the mine.

As the engine was designed to run slowly, the pumps had a capacity of over 300 gallons per stroke of the pistons. At ten revolutions per minute, this meant over 3,000 gallons of water poured out through a 28-inch pipe every minute. A total of 5,000,000 gallons of water could be removed from the mine each day. At that time the pump's estimated cost was nearly $250,000. After only a few years of successful operation, the giant pumping facility was moved from the "D" shaft of the Chapin Mine. More than a million tons of the best grade ore found in the entire mine was discovered directly below the pump, so it was essential that it be moved for excavation. In 1898 the pump was dismantled and stored away until 1907 when it was reassembled on the "C" shaft of the Chapin Mine. The pump operated here until 1932 when the Chapin Mine permanently closed its doors.

During the twentieth century, high grade ore, originally so plentiful on all three iron ranges, became less available and less profitable to mine. The cost of underground mining became more prohibitive, and the owners of Michigan's mines began to search for other methods of tapping the iron riches of Lake Superior. Many of the mining operations, such as the Lake Superior Iron Company, were absorbed by larger corporations. Between World War I and World War II, the total tonnage of iron ore shipped fluctuated drastically: in 1920, Michigan shipped over eighteen million tons of ore. In 1921, 1931, 1932, 1933, and 1934 Michigan shipped less than half that amount.

Extensive development of low grade ores and open pit mining began after World War 11, and a relatively new process, agglomeration, then began to yield an iron ore concentrate that contained about sixty-five per cent iron compared with fifty-six to sixty per cent from the average underground workings of the high grade ore. The first commercial agglomeration plant began operation in 1952. By 1964, four plants had been opened, and by 1969 only three underground mines were still in operation. Agglomeration, a process that separates iron ore and waste rock and then roasts the particles until they form small pellets or balls, kept Michigan's iron industry in a strong competitive position and is contributing another chapter in the seemingly endless history of Michigan's iron ranges.

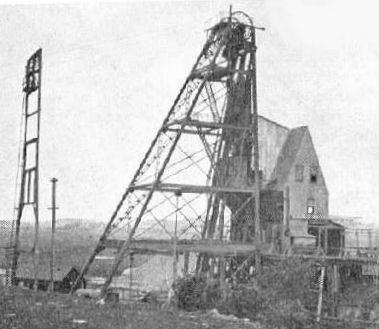

West Palms Mine - Bessemer, MI

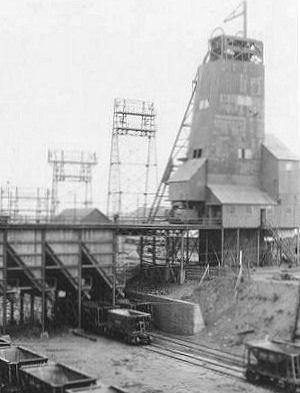

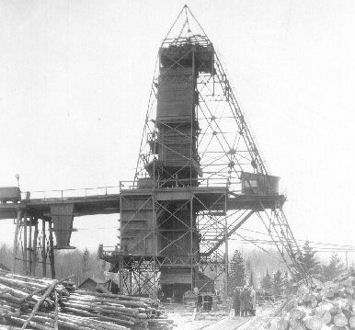

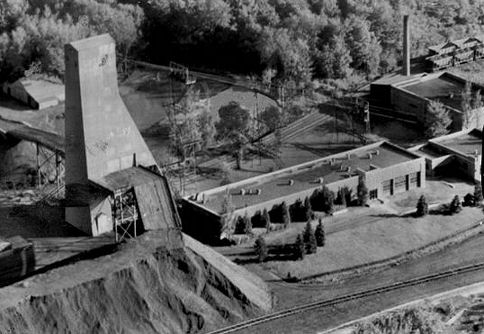

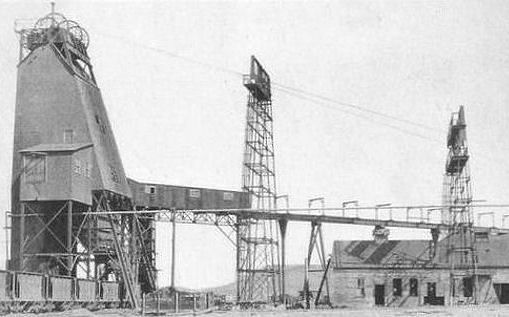

Eureka Mine No.4 Shaft - Ramsay, Gogebic County, MI

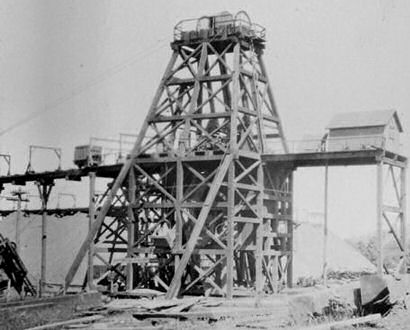

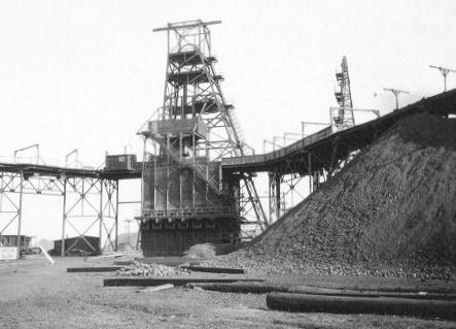

Anvil Mine - Bessemer, Gogebic Iron Range, MI

Newport Mine Bonnie K Shaft - Ironwood

Eureka-Asteroid Mine - Gogebic Range, Ramsay, MI

Palms Mine - Bessemer, MI

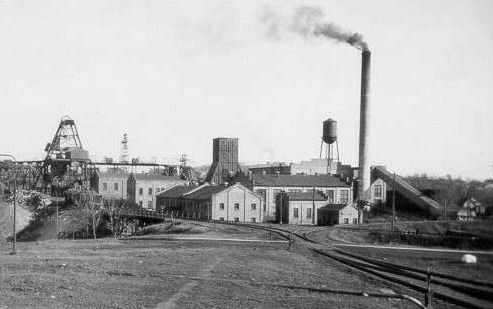

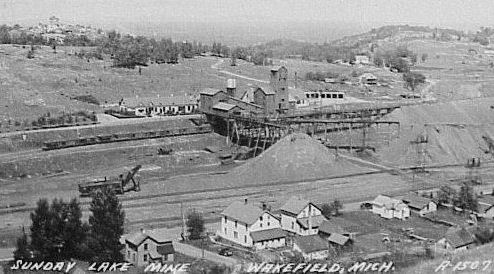

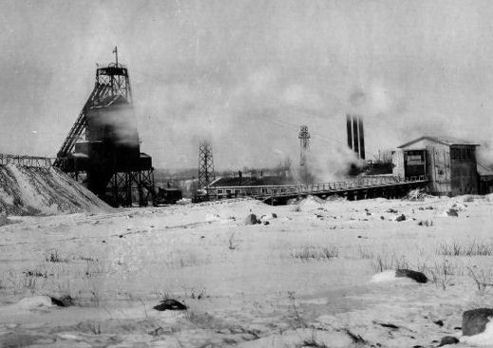

Sunday Lake Mine - Wakefield, MI

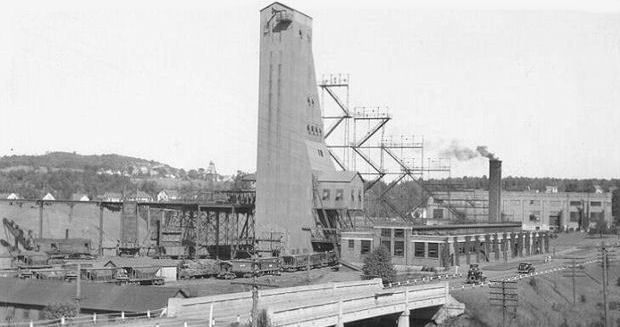

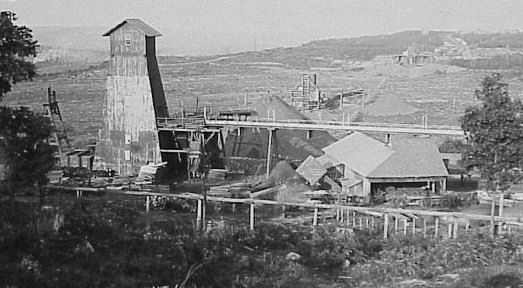

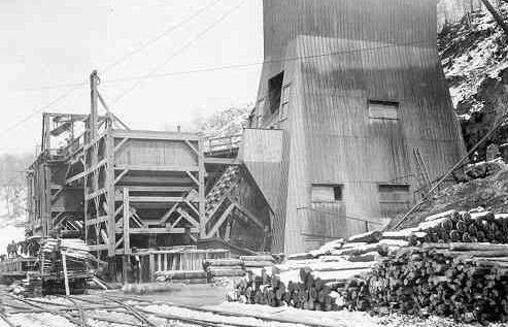

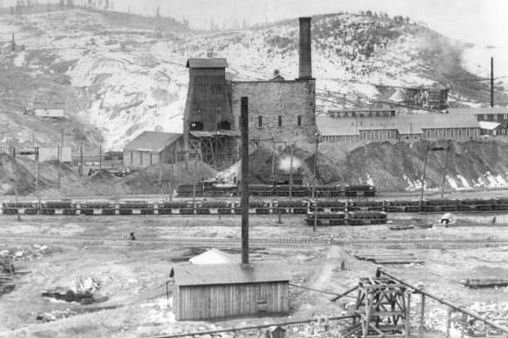

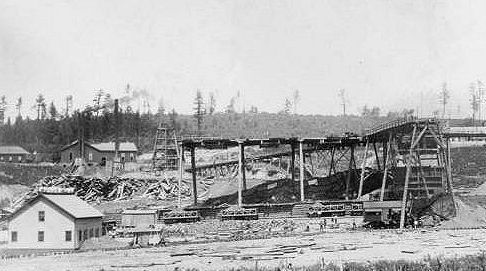

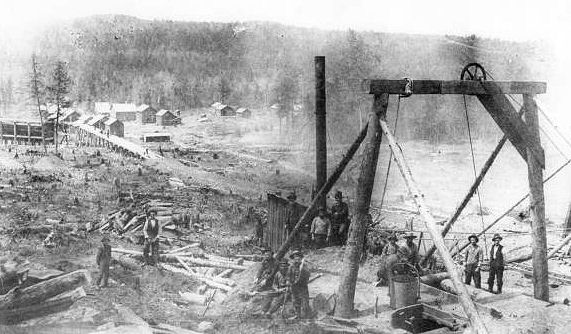

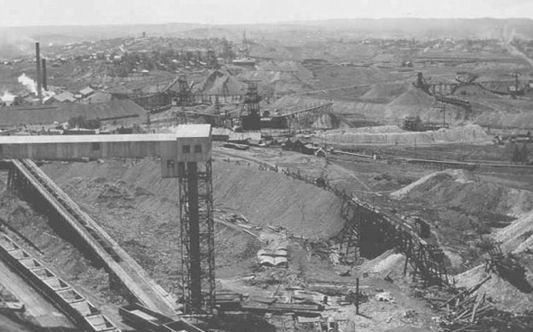

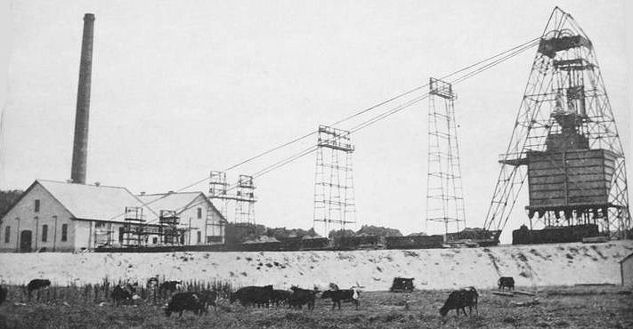

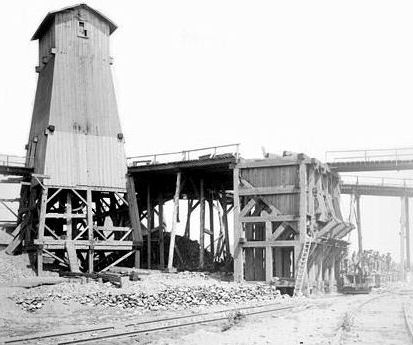

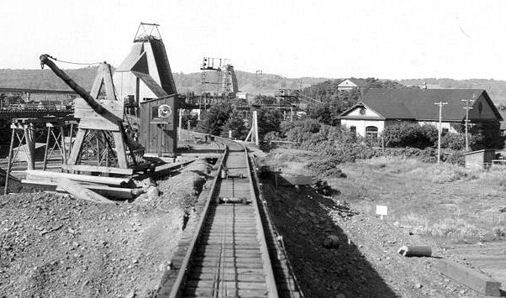

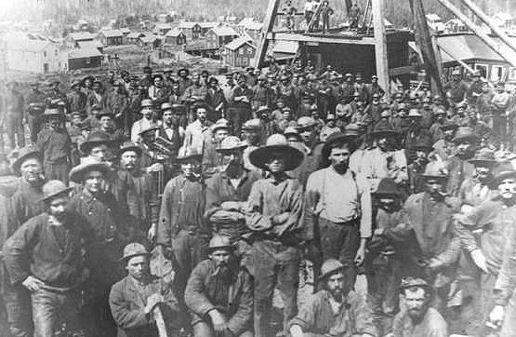

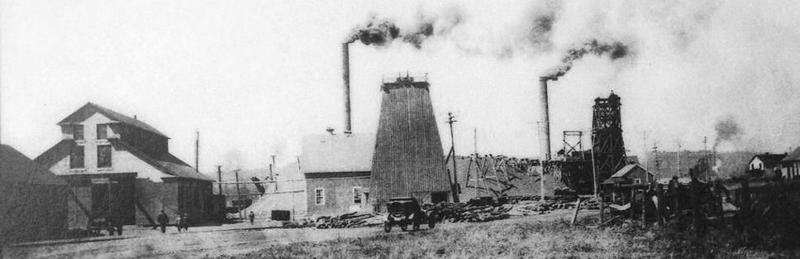

Colby Mine - Bessemer, MI

Colby Mine - Bessemer, MI

Colby Mine - Bessemer, MI

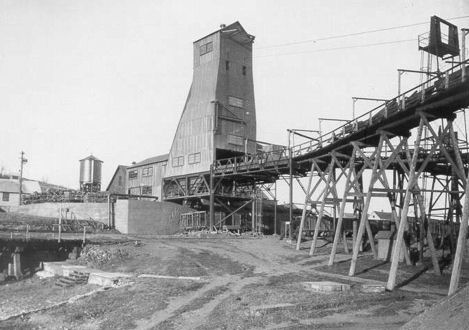

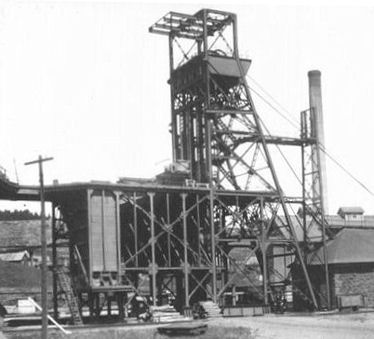

Newport Mine - Ironwood, MI

Aurora Mine - Ironwood, MI

Geneva Mine - Bessemer, MI

Geneva Mine - Bessemer, MI

Geneva Mine - Bessemer, MI

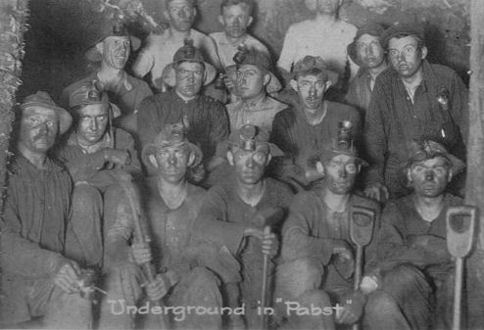

Pabst Mine G Shaft - Ironwood, MI

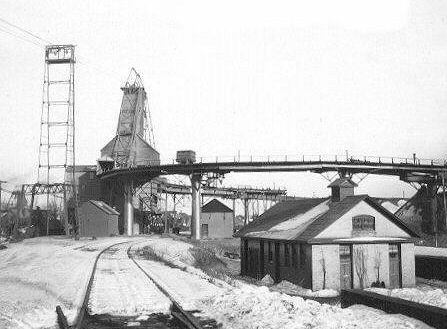

Pabst Mine C Shaft - Ironwood, MI

Ironton Mine, Corrigan Shaft - Bessemer, MI

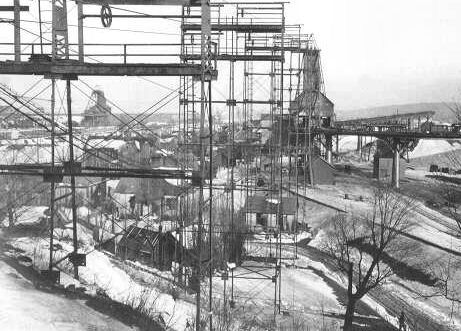

Pabst Mine H Shaft - Ironwood, MI

Peterson Mine - Ironwood, MI

Norrie Mine - Ironwood, MI

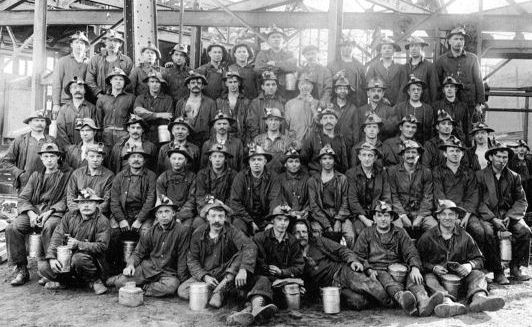

Pabst Mine - Ironwood, MI

Norrie Mine - Ironwood, MI

Newport Mine - Ironwood, MI

Athens Mine - Palmer, Marquette Iron Range, MI

Athens Mine - Palmer

Marquette Iron Range, MI

American Mine - Marquette Iron Range, MI

Section 16 Mine -Ishpeming - Marquette Iron Range, MI

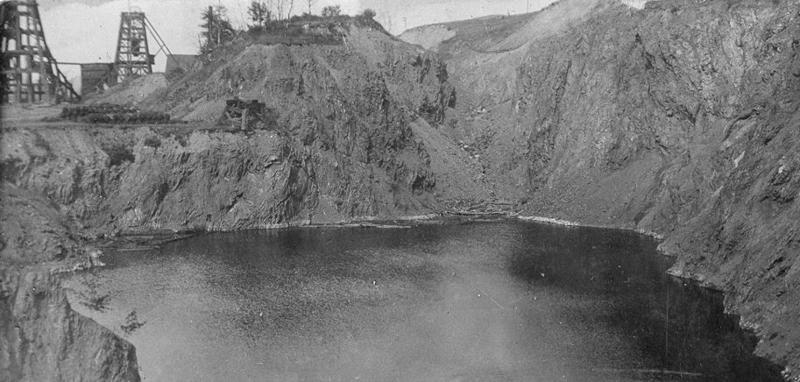

Lake Angeline Mine - Marquette Iron Range, MI

Lake Angeline Mine - Marquette Iron Range, MI

Lake Angeline Mine - Marquette Iron Range, MI

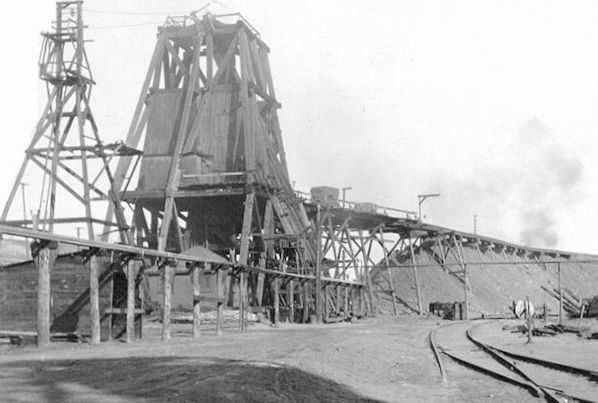

E. Lake Angeline Mine shaft house - Ishpeming, MI

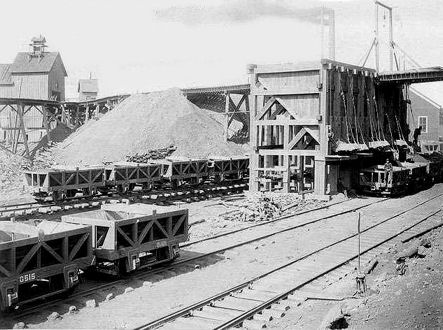

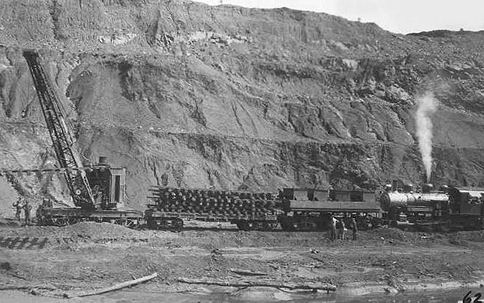

Laoding ore - E. Lake Angeline Mine - Ishpeming, MI

Loading ore - E. Lake Angeline Mine - Ishpeming, MI

Lake Mine - Ishpeming, Marquette County, MI

Lake Mine - Ishpeming, Marquette County, MI

Barnes & Hecker Mine - Negaunee, Marquette County, MI

In 1845 individuals from Jackson, Michigan started the first mine in Negaunee Michigan. The next mines that started in the following years were The "Cleveland" and "Lake Superior Mine", Located in Ishpeming. With more and more mine starting in the area, the "Iron Cliffs Mining Company" started the "Barnum" mine in 1867, just north of the "Lake Superior" Mines This mine operated very successfully for many years.

In the late 1870's The "Iron Cliffs Company" started some exploratory work to the north. Using a diamond drill to take core samples, the company started two holes. The Hole Numbered "A" in Section 10 on the high ground over looking the swamp of Ishpeming, was begun on March 15th 1877. On February 15th 1878, after going seventy-six feet through surface material and reaching a depth of 628 feet with no occurrence of ore found, the drilling was halted. During that time another diamond drill test was already being performed a short distance away to the west. The drill hole number "B", started on June 1st 1877. The drill proceeded to have 74 feet of surface material then continue till ore was discovered at a depth of four hundred to four hundred sixty feet down. Number "B" was completed in July of 1878.

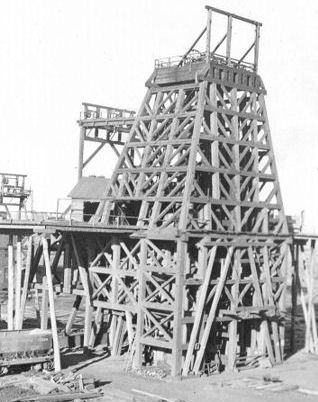

In the years to come, the two exploratory drill holes became mine shafts and the new operation was called the "New Barnum" In the Early 1880's, a New Engine house and Boiler House were constructed and a set of wooden shaft houses stood at either end of the property, along the shores of local Lake Bancroft. In 1886 The "New Barnum" name was changed to the "Cliff Shaft", however the mine would always be known by the miners that worked there as the "Barnum mine".

In May of 1891, the Iron Cliffs Mining Company merged with the Cleveland Mining Company to form the Cleveland-Cliffs Mining Company. The President of the new merger was William Gwinn Mather. The Cliffs Shaft became one of the principle mines to Cleveland-Cliffs. This new mine worked continually and successfully long after the "Old Barnum" open pit operation to the south closed in 1897.

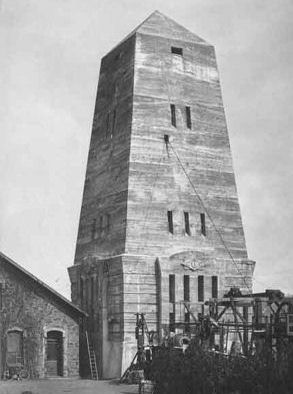

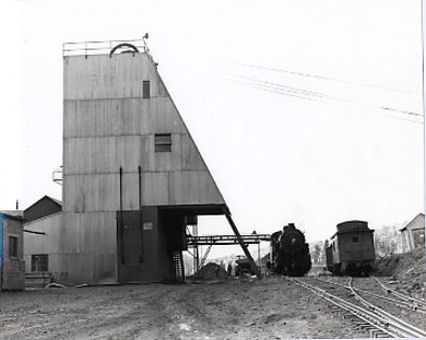

In 1919 the old wooden head frames needed to be replaced, and "William G. Mather" decided that the appearances of the shaft houses needed to be a factor in their construction. A famous architect named, George Washington Maher designed a 97 foot tall concrete "Egyptian Revival" Obelisk to be placed at both the A and B shafts. These structures would become icons of mining for the company and the area of Ishpeming.

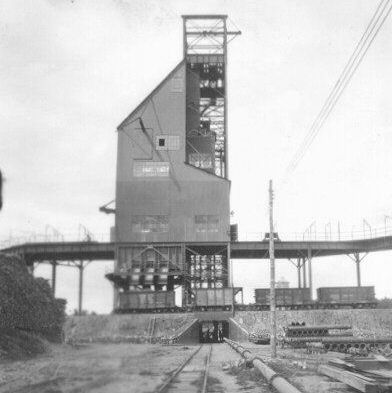

The old mine needed to be modernized by the 1950's. In the early winter of 1955 a new shaft was placed into service. This Shaft designated as the "C" Shaft, was located between the older two shafts and was marked by a 174 foot tall structure. The Sweden designed head frame contained three of Americas first Koepe hoist systems. The system worked on a counterweight system, which each skip or cage was balanced with a counter weight, and the hoist cables passed over shive wheels rather than on and off a large drum. Also the hoists were located directly above the shaft. The "A" and "B" shafts were taken out of service in the same year.

Even with the new operations the mine passed into its final year of operation. On December 22nd 1967 the Cliffs Shaft mine closed. This ended the longest operation of an underground iron mine in the world. With the ground breaking of the "Old Barnum" pit in 1867 to the last hoist of a skip full of ore on a Friday afternoon in 1967, the operations for this small location in the far north of Michigan operated for a hundred years. The test shafts of "New Barnum" mine had become the expansive operations of the "Old Cliffs Shaft". The mine had produced 27 Million tons of high grade ore, and had extensive workings below Ishpeming to a depth of 1357 feet.

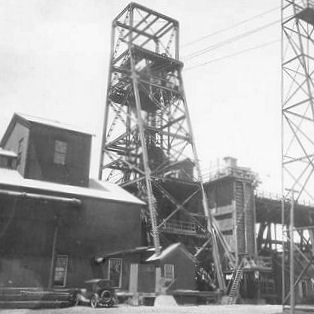

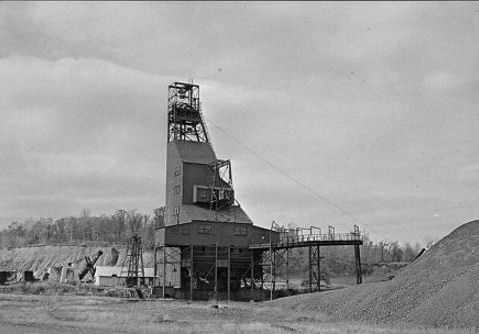

Cliffs Mine A & B Shafts - Ishpeming, Marquette County, MI

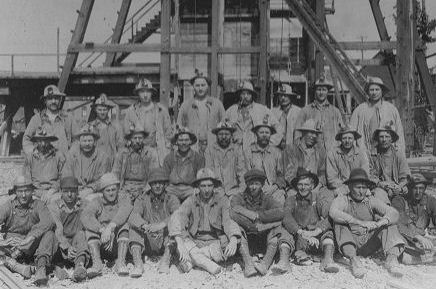

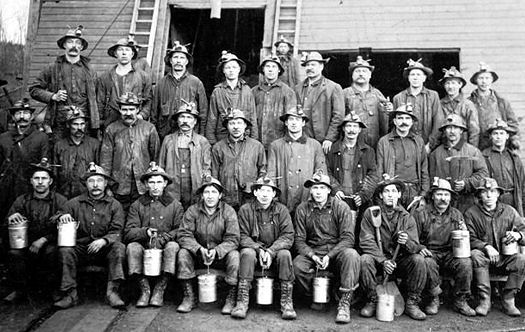

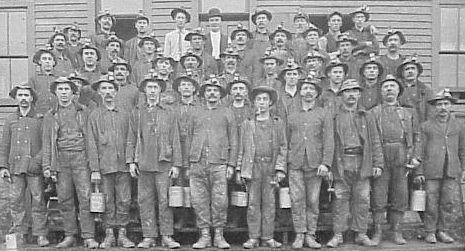

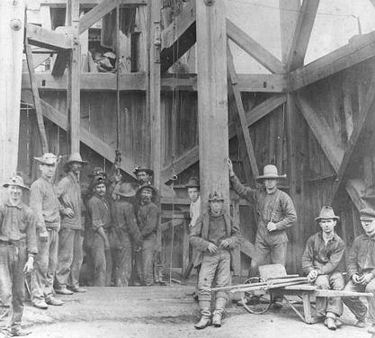

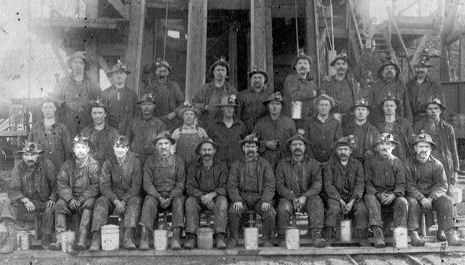

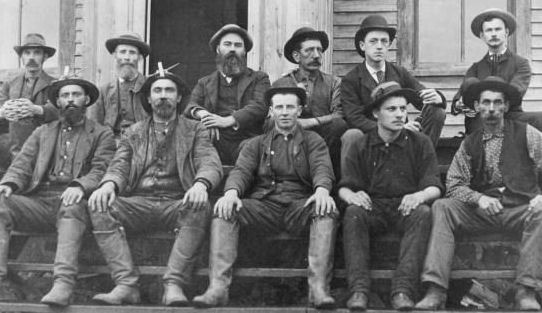

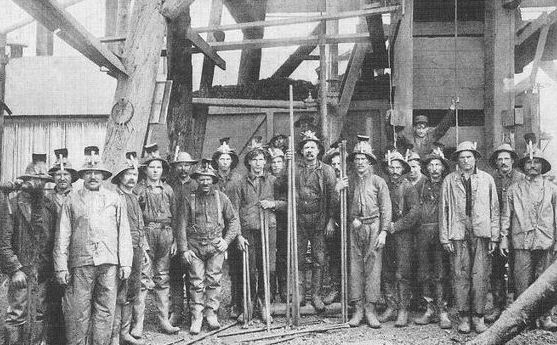

Cliffs Mine miners

Cliffs Mine Hoist Engine

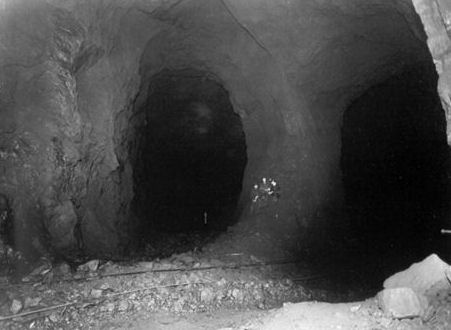

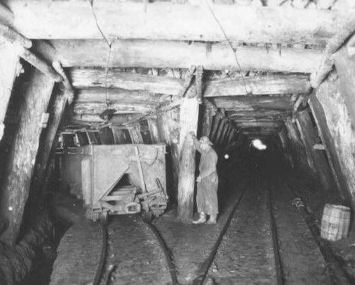

Cliffs Mine underground

Cliffs Mine A Shaft

Dexter Mine, Blueberry Shaft - Snowville, Marquette Range, MI

Dexter Mine, Blueberry Shaft

Snowville, Marquette Range, MI

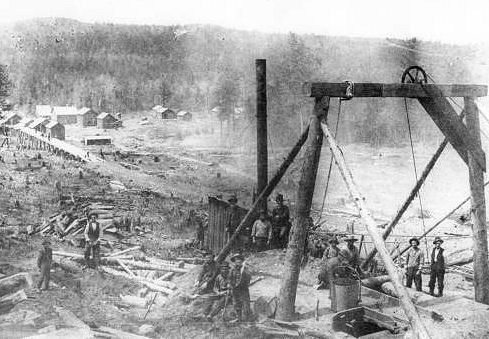

Jackson Iron Mine - Negaunee, MI - 1867

Jackson Iron Mine - Negaunee, MI

Negaunee Mine - Negaunee, Marquette Range, MI

Prince of Wales Mine

Marquette Iron Range, MI

Stephenson Mine - Gwinn, MI

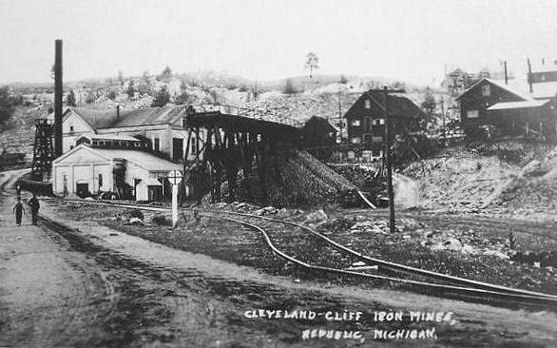

Republic Mine - Republic, Marquette County, MI 1907

Austin Mine - Gwinn, Marquette, County, MI

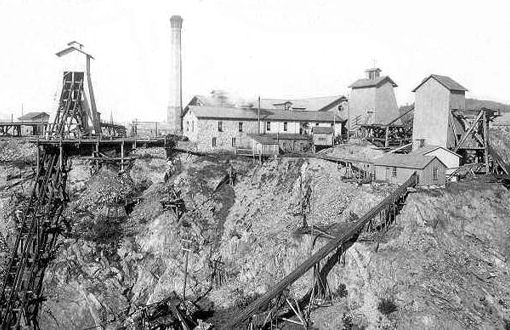

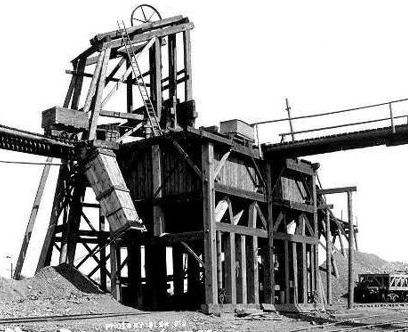

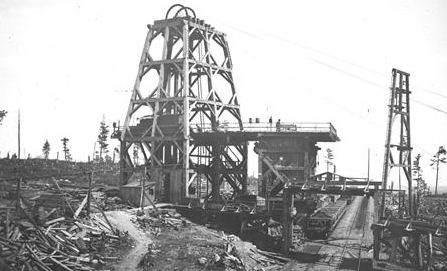

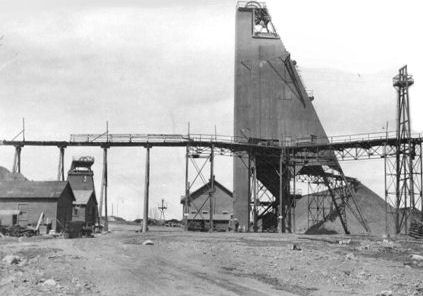

Chapin Mine D Shaft - Iron Mountain, Dickinson County, MI

Chapin Mine Hamilton Shaft

Chapin Mine - Iron Mountain, MI 1879

Chapin Mine - Iron Mountain, MI 1886

Ludington Mine C Shaft - Iron Mountain, MI

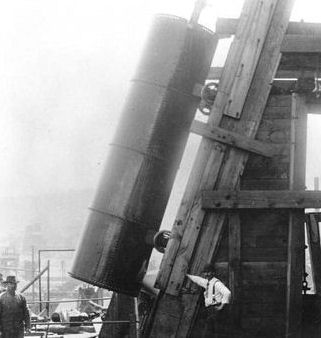

Cornish Pump - Chapin Mine

Traders Mine - Iron Mountain, MI

Pewabic Mine - Iron Mountain, MI

Pewabic Mine - Iron Mountain, MI

Cundy Mine - Quinnesec, Dickinson County, MI

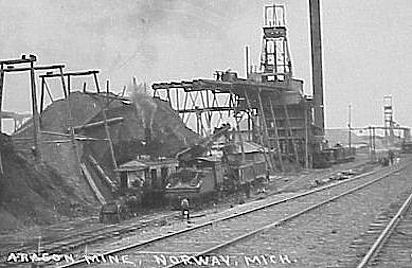

Aragon Mine Shaft No.4 & Brier Hill Mine New Shaft - Norway, MI

Brier Hill Mine - Vulcan, MI

Brier Hill Mine - Vulcan, MI

Central Vulcan Shaft - Vulcan Iron Co. - Vulcan, MI

Vulcan Mine Vulcan, MI

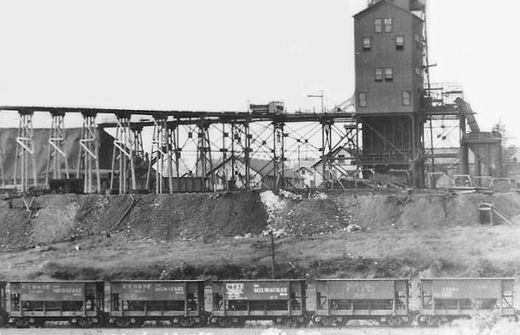

Vulcan Mine, Vulcan, Dickinson Co. MI

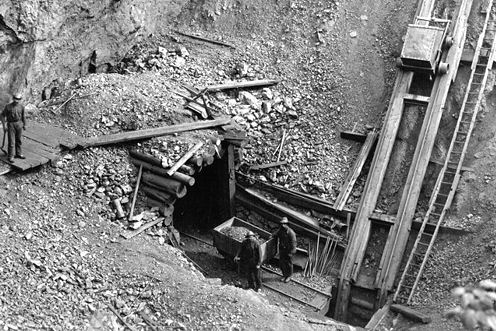

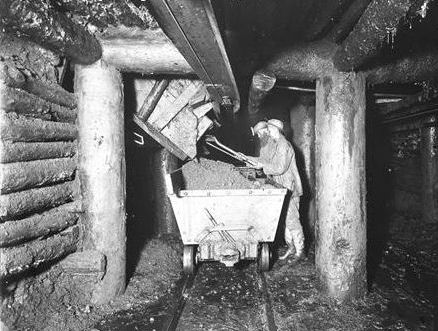

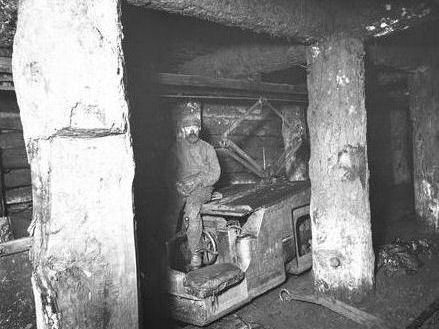

Setting Timber - Vulcan Mine - Vulcan, MI

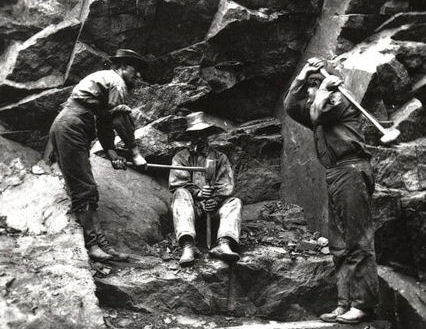

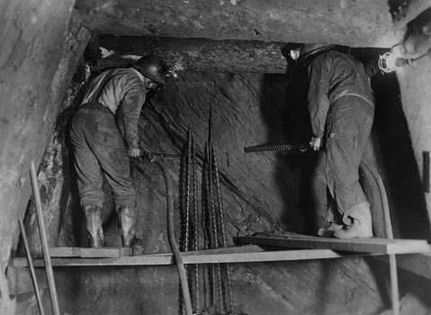

Drilling - Vulcan Mine - Vulcan, MI

Drilling - Vulcan Mine - Vulcan, MI

Drilling - Vulcan Mine - Vulcan, MI

Curry Mine - Vulcan, MI

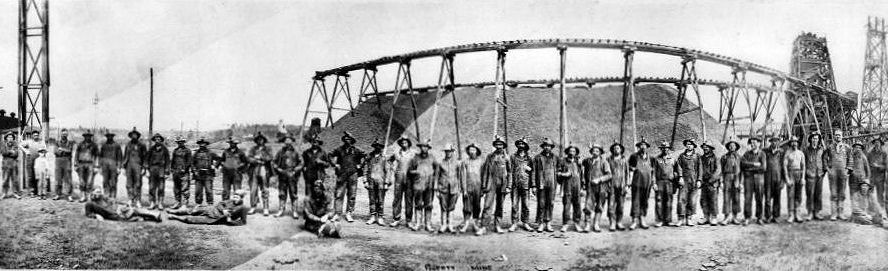

Vulcan Mine - Vulcan, MI 1880

Bengal Mine - Stambaugh, Iron County, MI

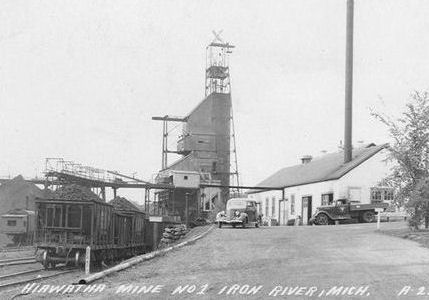

Drilling - Hiawatha Mine No.1 1935

McKinney Steel Co. Tobin Mine - Crystals Falls, MI

Tully Mine - Stambaugh, Menominee Iron Range, Iron Co., MI

Odgers Mine - Crystal Falls, Menominee Range, MI

Berkshire Mine, Berkshire Shaft No.1 - Gaastra, MI

Berkshire Mine, Berkshire Shaft No.2 - Gaastra, MI

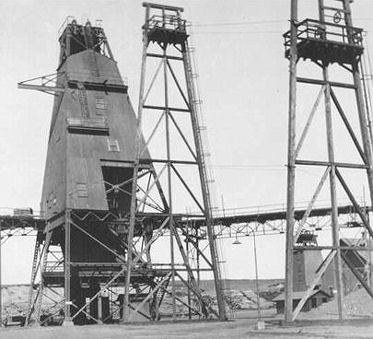

Tilden Mine No. 9 & 10 Shafts - Bessemer, Gogebic Range, MI

Tilden Mine No. 9 & 10 Shafts - Bessemer, Gogebic Range, MI

West Palms Mine - Bessemer, MI

The range became the center of frenzied economic speculation during the late 1880s, and the total capitalization for the companies formed in the year 1886 reached a total of over one billion dollars. Over-speculation naturally brought a resultant crash, and most of the smaller investing companies were eliminated. The larger workings held their ground, however, and production rose steadily from 1884, reaching a high water mark in 1892. From 1893 through the first decade of the twentieth century, production levels ranged from approximately three million tons of ore to four million tons shipped, and the Gogebic continued to be a productive iron range

Eureka Mine No.3 Shaft - Ramsay, MI

Timbering in the Ironton Mine - Bessemer, MI

Sunday Lake Mine - Wakefield, MI

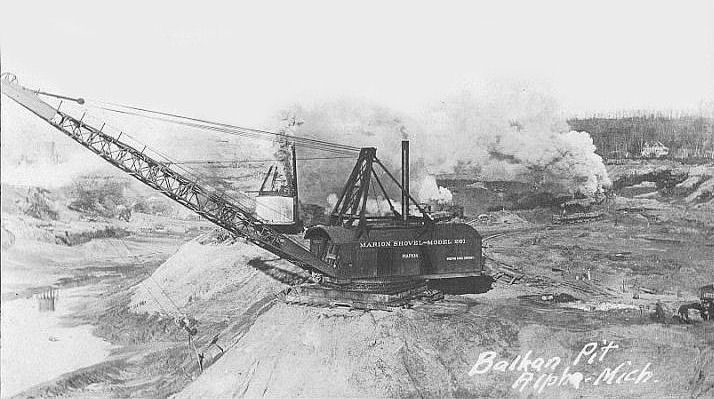

Plymouth Open Pit - Wakefield, MI

Newport Mine - Ironwood, MI

Making clay stemming cartridges - Sunday Lake Mine, Wakefield, MI

Peterson Mine - Ironwood, MI

Norrie Mine Group Shaft No.3 - Ironwood, MI

Norrie Mine East "C" Shaft

Newport Mine Woodbury Shaft - Ironwood, MI

Looking east from Newport Mine Woodbury Shaft

Norrie Mine - Ironwood, MI

Cage - Athens Mine, Palmer, Marquette Range, MI

Imperial Mine - Marquette Co., MI

East Lake Angeline Mine - Marquette Iron Range, MI

Timbering Trucks - Athens Mine - Marquette Range, MI

Lake Shaft, Cleveland Mine - Ishpeming, MI

Lake Superior Iron Mine - Marquette Co., MI.

Breitung Mine - Negaunee, Marquette County, MI

Cliffs Mine Bath House

Cliffs Shaft - dumping ore cars underground

Buffalo Shaft - Negaunee, MI

Empire Mine - Marquette Co., MI

Negaunee Mine - Negaunee, MI

Face of Advancing Top Slice - Negaunee Mine - Negaunee, MI

Bailing skip - Hamilton Shaft, Chapin Mine - Iron Mnt.

Cundy Mine - Quinnesec, Dickinson County, MI

Tully Mine - Stambaugh, MI

Ludington Mine C Shaft - Iron Mnt.

Ludington Mine - Iron Mountain, MI

Traders Mine - Iron Mountain, MI

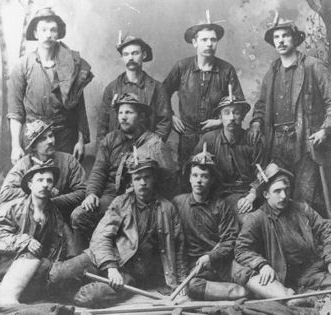

Pewabic Mine Miners

West Vulcan Mine, Dickinson Co. MI

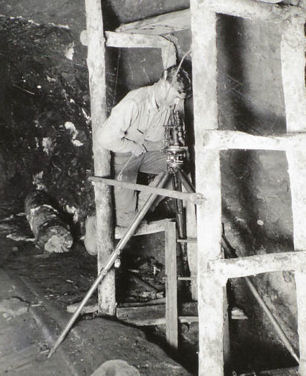

Surveying - Curry Mine, Vulcan, MI

Penn Mining Co. Vulcan, MI

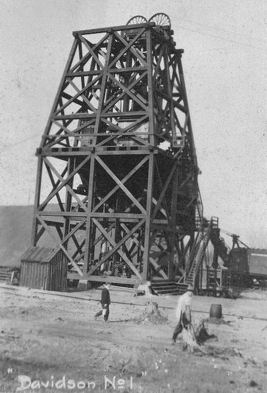

Davidson No.1 Mine - Mineral Hills, Iron Co.

Fogarty Mine, - Gaastra, Iron Co. MI

Penn Iron Mining Co. Vulcan, MI

Drilling - Judson Mine - Alpha, Iron Co. MI

Iron Mine - Fortune Lake, Iron County, MI

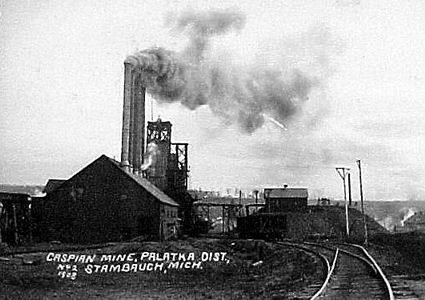

Verona Mining Co. Caspian Mine - Caspian, MI

Hiawatha Mine - Iron River, MI

Zimmerman Mine - Gaastra, Menominee Range, Iron County, MI

Shaft No.3 Caspian Mine - Caspian, Iron Co., MI

Caspian Mine - Caspian, Iron Co., MI

Carpenter Mine - Crystal Falls, MI

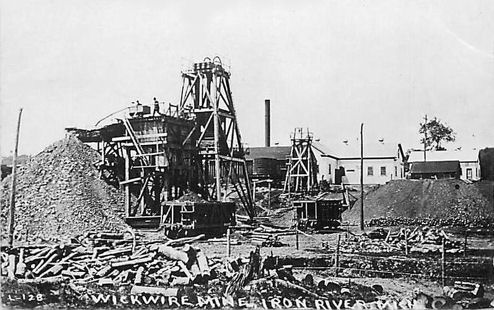

Wickwire Mine - Iron River, MI

Judson Mine - Alpha, Iron County., MI

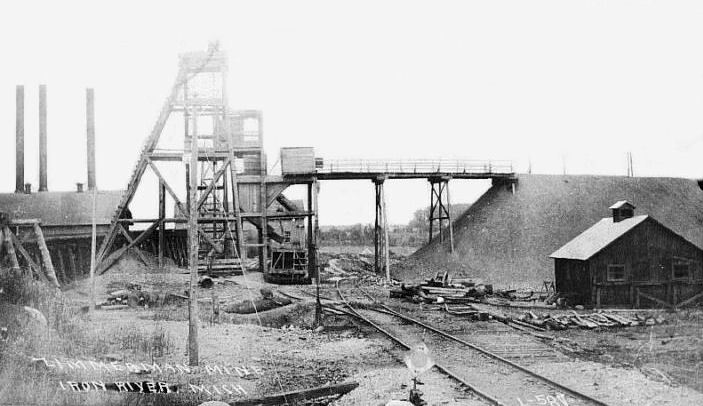

Hiawatha Mine -Iron River, MI

Chatham Mine - Iron River, MI

Homer-Waseca Mine - Iron River, MI

Iron Mine - Republic, MI

Vicar Mine - Wakefield, MI

Anvil Mine - Bessemer, MI

Puritan Mine - Bessemer, MI

Yale Mine - Bessemer, MI

Plymouth Open Pit - Wakefield, MI

Riverton Mine shafts & open pit - Stambaugh, MI

Vulcan Mine - Vulcan, MI