Scottish Mines

Coal has been central to the story of Scotland over much of the past two centuries. A chance of geology meant that a large part of the heart of the country was home to a series of rich coalfields extending from Ayrshire in the south west through Lanarkshire, the Lothians, Stirling, Clackmannanshire and Fife. But although the central belt of Scotland was home to most mining activity, outlying coalfields meant that mines existed as far west as Machrihanish in Kintyre; as far south as Canonbie in Dumfries & Galloway; and as far north as Brora in Sutherland.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, coal miners in Scotland, and their families, were bound to the colliery in which they worked and the service of its owner. This bondage was set into law by an Act of Parliament in 1606, which ordained that "no person should fee, hire or conduce and salters, colliers or coal bearers without a written authority from the master whom they had last served". A collier lacking such written authority could be "reclaimed" by his former master "within a year and a day". If the new master did not surrender the collier, he could be fined and the collier who deserted was considered to be a thief and punished accordingly. The Act also gave the coal owners and masters the powers to to apprehend "vagabonds and sturdy beggars" and put them to work in the mines. A further Act of 1641 extended those enslaved to include other workers in the mines and forced the colliers to work six days a wee.k

The process of emancipation began with an Act of Parliament of 1775 which freed the colliers in age-groups - those under 21 and between 35 and 44 were to be freed in 7 years, those between 21 and 34 were to be freed in 10 years and those over 45 were to be freed in 3 years. The liberation of the father freed the family. However, gaining freedom required a formal legal application before a Sheriff and a great many colliers continued to be bound until 1799 when an Act was passed that all colliers in Scotland were "to be free from their servitude".

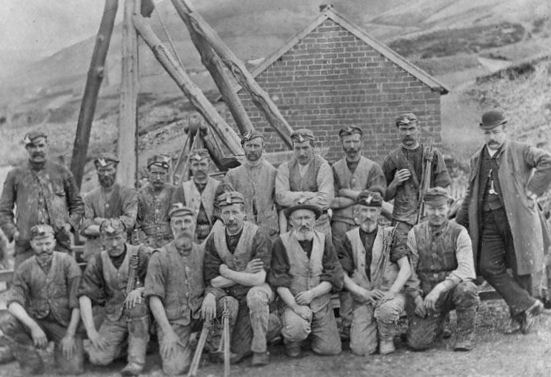

By the early years of the 1900s, nearly 150,000 people were directly employed in Scotland's mining industry; out of a total population at the time of around 4.5 million. Scotland's coal industry produced over 40 million tons of coal each year, and powered much of the rest of the country's economy at a time when Glasgow was generally considered to be the second city of the British Empire.

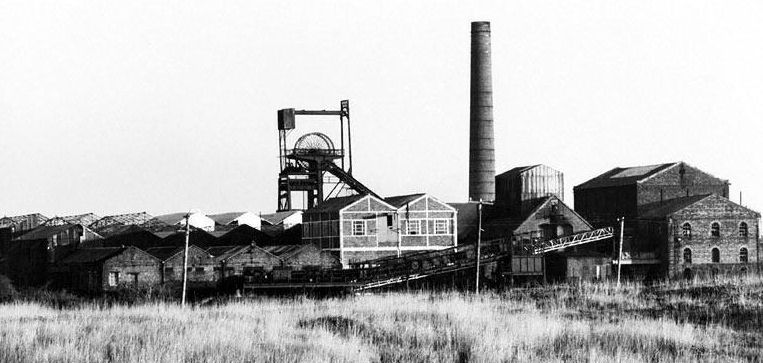

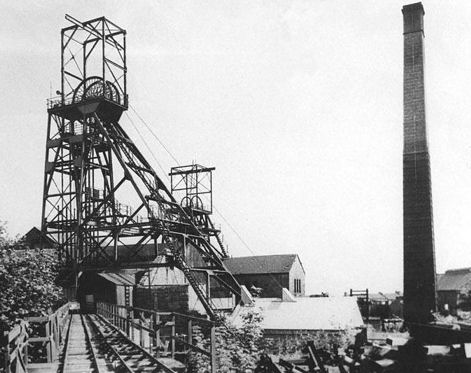

Lady Victoria Colliery, named after the wife of the ninth Marquis of Lothian, is located at Newtongrange, Midlothian, Scotland. It was sunk in 1890 by the Lothian Coal Company as part of the "Newbattle group" closely linked with Easthouses and Lingerwood. It was Scotland's second largest colliery. Lady Victoria Colliery worked six seams: the Jewel giving high-class household coal and the famous 'Newbattle Cannel' for gas-making; the Splint and Kailblades producing steam coal; the Coronation and Diamond giving household coal; and the Great Seam.

From its earliest days, when engineers used new brick-lining techniques to sink the shaft, the Lady Victoria was a proving ground for innovative technologies, including steel pit-props and the use of electricity for power as well as light. In its lifetime, it produced a record 40 million tons of coal, all hauled up the 500-metre shaft by the largest winding engine in Scotland. At its peak, the colliery had a workforce of almost 2,000 men and women. Today the Lady Victoria Colliery is preserved and houses the Scottish Mining Museum.

Lady Victoria Colliery, Newtongrange, Midlothian

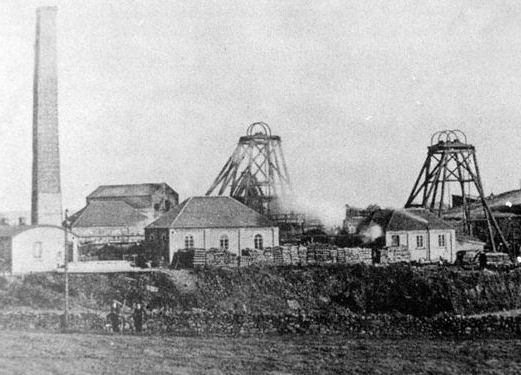

Beoch Colliery, Ayrshire

Carberry Colliery Rescue Brigade, Midlothian

Pennyvennie Colliery, Dalmellington, Ayrshire

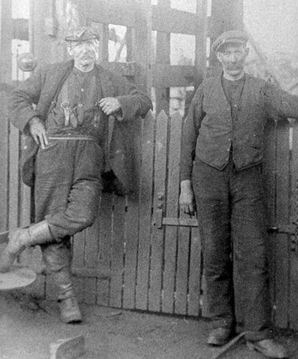

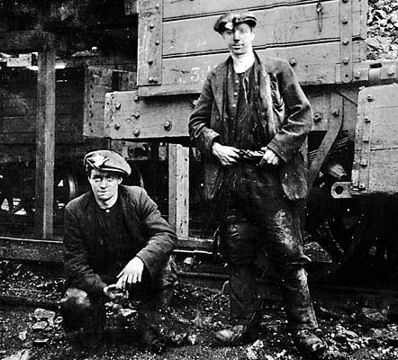

Coal miners near Edinburgh

Larbert Mine Rescue Brigade - Larbert, Falkirk, Scotland

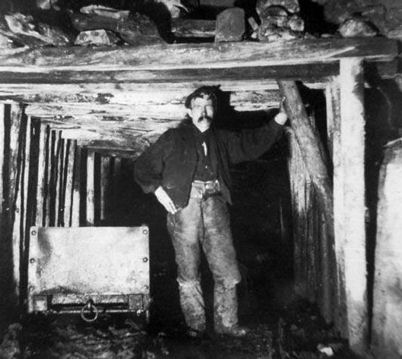

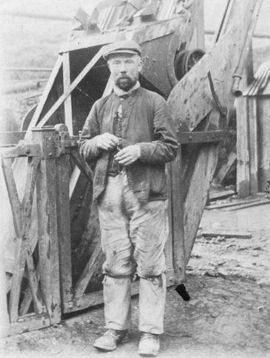

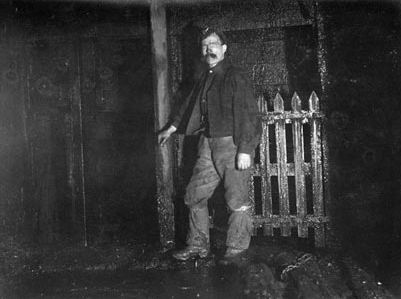

Miner, Glencrieff, Wanlockhead, Dumfriesshire

Roslin Colliery Rescue Brigade, Midlothian

Camp Colliery, Motherwell, c1890

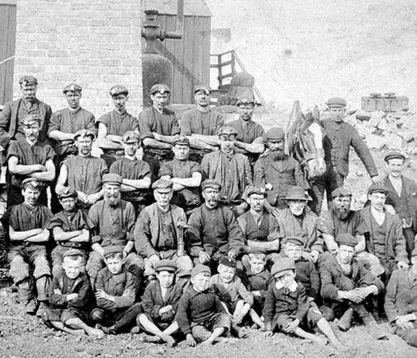

Coal Miners - Houldsworth Colliery, Ayrshire

Rescue Team - Oarbank Mine - East Calder, West Lothian, Scotland

Polkemmet Colliery - Whitburn, West Lothian, Scotland

Redding Colliery - Redding, Falkirk, Scotland

Maltby Main Colliery Rescue Team, St Ann's, Rotherham

Though the existence of ironstone in the Scottish coal measures was known many years previously, no attempt was made to turn it to account until the year 1760, when the Carron Ironworks were established. Only one kind of ironstone was then used - namely, the argillaceous or "clayband;" for the more valuable carbonaceous or " blackband " was not discovered till the beginning of the 20th century. These two varieties are known as the coal measure ironstones, and are found in all the great coal fields of Britain except those of Northumberland, Durham, and Lancashire.

From the establishment of the Carron Ironworks in 1760 till 1788, the quantity of iron produced in Scotland did not exceed 1500 tons per annum ; but during the succeeding eight years a number of new furnaces were erected in the counties of Lanark, Fife, and Ayr. In 1706 the number of furnaces was seventeen, and the quantity of iron made in that year was 18,640 tons. Thirty-three years afterwards the prod action had reached 29,000 tons ; and from that figure the invention of the hot-blast process raised it to 75,000 tons in 1836. By that time the construction of railways had begun to open a new market for the iron-merchant ; and to supply the demand, many new ironstone pits were opened, and furnaces erected. In the ten years from 1835 to 1845, the production of iron increased about 700 per cent. — the quantity made in the latter year being 475,000 tons. Ten years later, 825,000 tons were made ; and another decade gave an addition of 339,000 — the quantity manufactured in 1865 being 1,164,000 tons. Over speculation, and the consequent financial crisis in 1866, operated most prejudicially on the iron trade, and the production for that year fell to 994,000 tons. Matters gave promise of taking a turn for the better in 1867 ; but the promise was realised only to a limited extent, the revelations made in connection with several of the principal railway companies, and other causes, having had an unfavourable effect on the trade. The total quantity made in 1867 was 1,031,000 tons — an increase of 37,000 as compared with the preceding year, but 133,000 tons short of the production of 1865. The quantity shipped in each of the past ten years has not varied much. In 1867 it was 593,277 tons, of which 338,364 tons were for foreign ports, and the remainder went coastwise. Of the quantity shipped to foreign ports, France took 60,500 tons ; Germany and Holland 99,600 tons; Belgium, Denmark, Sweden, and Norway, 20,100; Russia, 9600; Spain and Portugal, 5100; Italy, 14,200; United States, 117,300; British America, 43,000; East Indies, China, Australia, and South America, 14,000. The largest quantity ever consumed in Scotland in one year was 532,000 tons, in 1865. In 1867, the quantity taken was 420,262 tons. The make of malleable iron in 1867 was 142,800 tons, being a reduction of 11,400 tons as compared with 1866.

The 1800's saw a massive rise in the amount of coal and iron mines as the industrial revolution swung into full effect. In 1879 there were 314 iron-works with 5149 puddling furnaces and 846 rolling mills in operation in Lanarkshire and in 1881, 392 coal pits and 9 fireclay pits. This labour force was found principally in Irish emigrants who were refugees from the suffering and deprivation caused by the potato famine in Ireland. Places like Blantyre were reputed to be, at this time; "a district of pits, engine houses, smoke and grime", this description no doubt led to the nickname the town endured for many years as "Dirty Auld Blantyre".

Lanarkshire was rich in coal, with numerous early mines scattered over the county. Around 1910 the actual amount of working collieries reached their peak with around 200 in the county. Between the wars mining started to decline and miners had to travel to work, or be re-housed near the pits.

Lead was mined from the Lowther Hills in Roman times. One early use of the mineral was as a food preservative! Scottish kings called this area of the Southern Uplands ‘God’s Treasure House’, because of all the precious metals to be found there alongside the lead: most notably, high-quality silver and gold.

The village of Leadhills, in South Lanarkshire, stands at 395m above sea level. It had numerous lead mines which, at their peak output around 1810, produced 1400 tons annually. Miners clubbed together here in 1741 to form the first subscription library in Scotland. The mining ceased here in 1928.

Wanlockhead, in Dumfriesshire, owes its existence to the lead and other mineral deposits in the surrounding hills. These deposits were first exploited by the Romans, and from the 13th century they began to be worked again in the summer. The village was founded permanently in 1680 when the Duke of Buccleuch built a lead smelting plant and workers' cottages. Lead, zinc, copper and silver were mined nearby, as well as some of the world's purest gold at 22.8 carats, which was used to make the Scottish Crown. Wanlockhead became known as "God's treasure house" from the richness of its mineral resources. Despite a branch railway, also the highest in Scotland, serving the village from 1901 to 1939, lead mining declined in the 20th century and finished in the 1950s. The village had a curling club which was formed in 1777 and there were also quoits, bowling clubs, a drama group and a silver band which had instruments purchased for them by the Duke of Buccleuch.

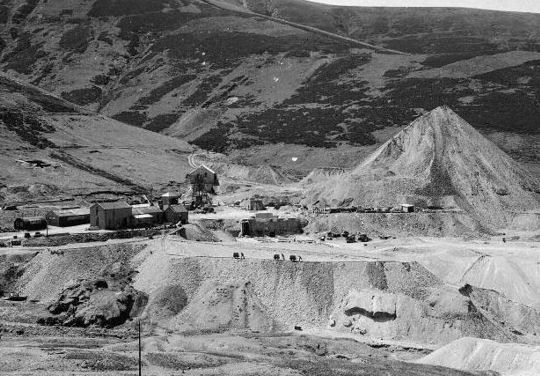

Glencrieff Lead Mine - Wanlockhead, Dumfriesshire, Scotland

Glencrieff Lead Mine - Wanlockhead, Dumfriesshire, Scotland

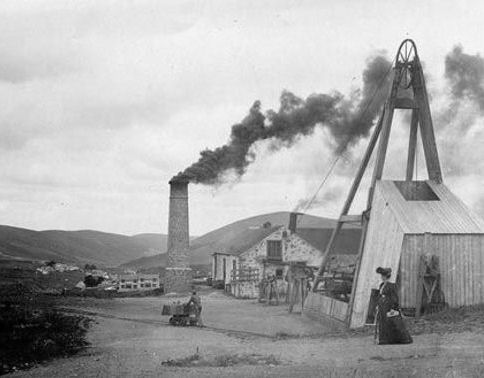

Wilson's Shaft - Leadhills Silver-Lead Mining & Smelting Co. Leadhills, Lanarkshire

Straitsteps Lead Mine - Wanlockhead, Dumfriesshire

Shotts Iron Co. Ramsay Colliery - Loanhead, Midlothian

Working a 16 inch seam - Canderigg Colliery - Larkhall, Lanarkshire

Lanarkshire Pit Pony at Work

Herbertshire Colliery Pit No 3, Denny, Falkirk

Overman - Summerlee Iron Co. Camp Colliery - Motherwell, Lanarkshire

Pit ponies - Summerlee Iron Co. Camp Colliery, Motherwell, Lanarkshire

Shaftsmen - Summerlee Iron Co. Bardykes Colliery, Lanarkshire

Redding Colliery - Redding, Falkirk, Scotland

Hassockrigg Colliery, Shotts, Lanarkshire

Summerlee Iron Co. Prestongrange Colliery, Prestonpans, East Lothian