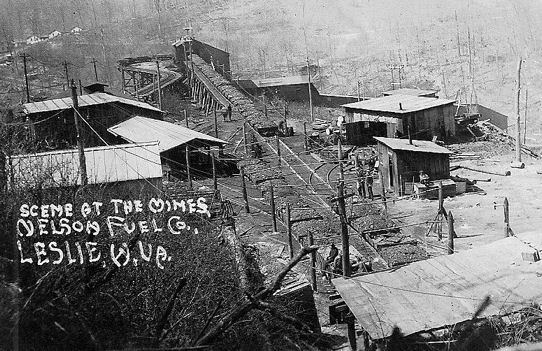

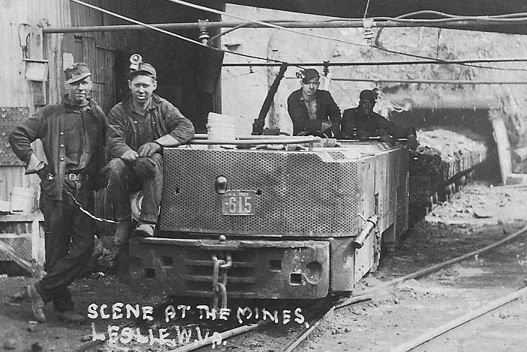

WEST VIRGINIA MINES

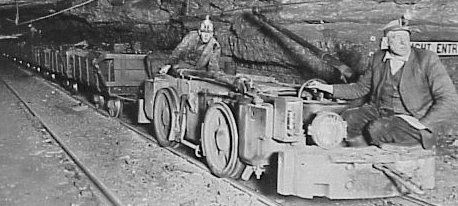

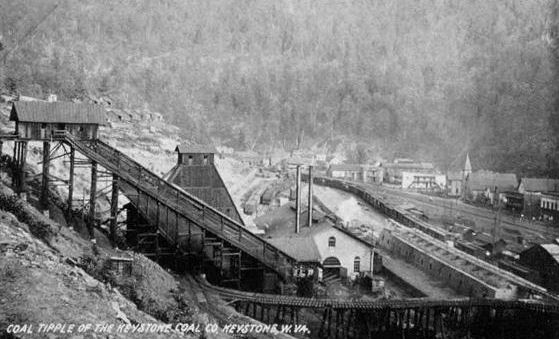

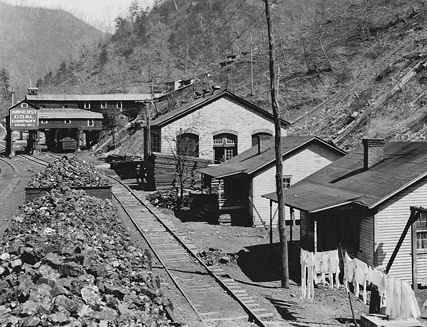

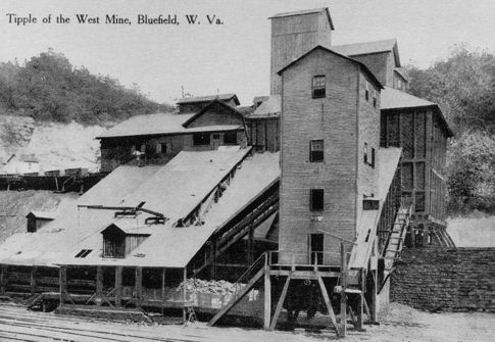

Amherst Coal Co. Mine No.2 - Logan Co., WV

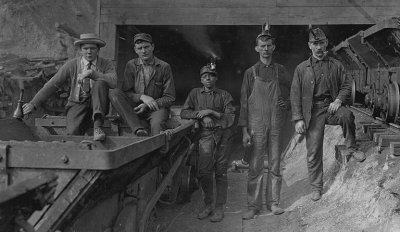

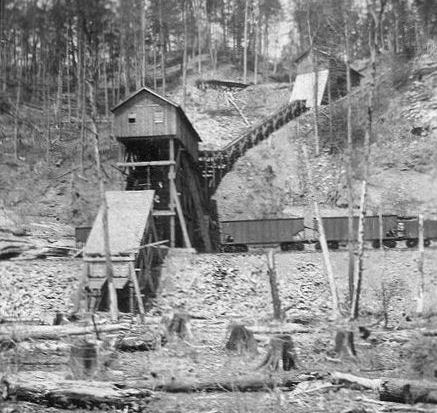

Laura Mine - Red Star, WV

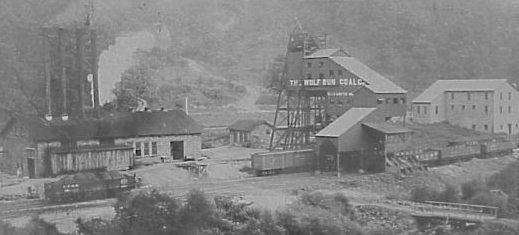

Wolf Run Coal Co. - Elizabeth Mine, WV

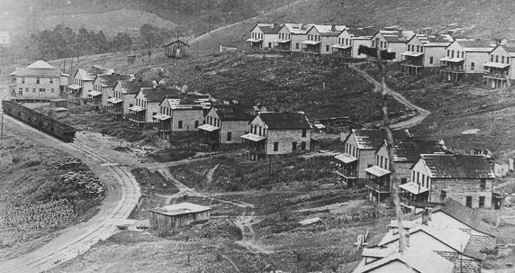

Cliftonville, WV 1922

Miner's Home - Bream, WV

Coal Company Owned Miners' Homes - Bream, WV

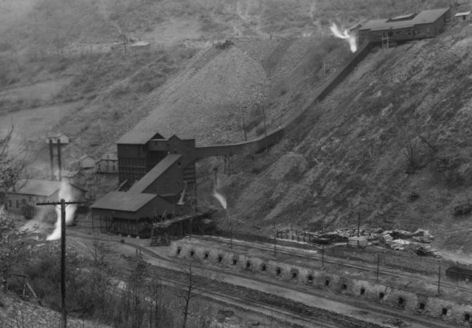

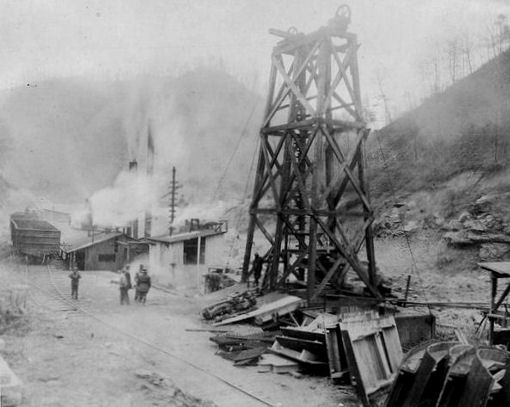

Burning Tipple - Cliftonville, WV 7-18-22

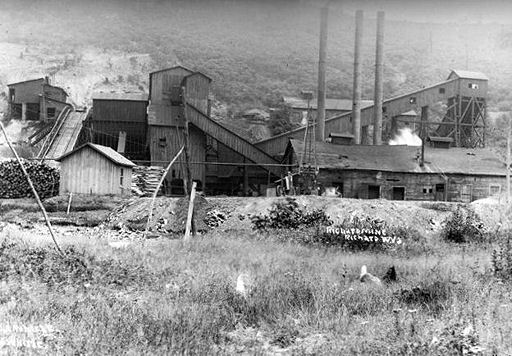

Saladka Mine - Richland Coal Co. Cliftonville, WV 7-19-1922

Woolridge Mine - Nicholas County, WV

Coal occurs in 53 of West Virginia's 55 Counties, only Jefferson and Hardy counties in the eastern panhandle have no coal. Forty-three of these counties have reserves of commercially minable coal. There are 117 named coal seams in West Virginia, sixty-five seams are considered minable and fifty-four are producing coal today, with coal mined in 26 counties. The Pittsburgh coal seam alone accounted for nearly 33 million tons of production in 2008.

West Virginia produces about 15 % of total coal production in the U.S.West Virginia leads the nation in coal exports with over 50 million tons shipped to 23 countries. West Virginia Coal accounts for about 50% of US coal exports.

John Peter Shirley made the first recorded discovery of coal in the area now comprising West Virginia in 1741, while crossing the Allegheny Mountains. His report became the first reference to coal in what is today West Virginia.

In 1770 future founding father and president George Washington noted "a cole hill on fire" near West Columbia in current Mason County. The large Pittsburgh Coal Seam was discovered in northern Kanawha County in 1800. The first commercial coal mine opened in 1810 by Conrad Cotts near Wheeling, with the coal used for blacksmithing and home heating.

Although coal was known to occur throughout much of West Virginia, no extensive mining took place until the mid-1800s. Until that time, there was little incentive to exploit coal as a resource because of the great abundance of wood and a lack of manufacturing industries. Small amounts of coal were used by crossroads blacksmiths or by the settler whose cabin stood near an outcrop. In 1810, the people of Wheeling began to use coal obtained from a nearby mine to heat their dwellings. In 1811, the first steamboat on the Ohio River burned coal from Ohio. By 1817, coal began to replace charcoal as a fuel for the numerous Kanawha River salt furnaces. By 1836, the western Virginia coal fields had received so much attention that Virginia's foremost geologist, Professor William B. Rogers, was sent to visit the mines and analyze the coal in eight counties. The total coal production in 1840 for the State was about 300,000 tons, of which 200,000 tons was used in the Kanawha salt furnaces and most of the remainder was consumed by factories and homes in Wheeling.

In 1834, the first commercial coal mining company in the Kanawha Valley was incorporated and began production. By 1843, the Baltimore and Ohio railroad reached Piedmont and coal was being shipped to markets in Baltimore, Maryland. Coal began being shipped by river from Mason County to distant markets in 1847. Transportation improvements continued to allow for the increased mining and shipping of coal, as was evidenced bvy the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad reaching Wheeling in 1853. Between 1840 and 1860 many coal companies were organized, and corporations were created under the laws of Virginia for the purpose of encouraging financial investments from foreign countries.

With the outbreak of the Civil War, the Kanawha Valley mines were closed. Confederate troops set up camps in the valley, and many of the locks and dams along the river were destroyed, thus preventing shipping. Farther north, the Elkins and Fairmont fields remained active, providing coal for the Union via the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. The coal was used by railroad and for heating in the east.

Following the Civil War, an awakening of interest in the State's mineral resources brought a new era of development and growth for the coal industry. The industry spread to new localities, and by 1880 there were extensive operations in Mineral, Monongalia, Marion, Fayette, Harrison, Ohio, Putnam, and Mason counties. Of the numerous coal fields which grew up in West Virginia, a few are of particular interest. One of the larger fields is the Fairmont Field, developed around the rich Pittsburgh seam. The first marketed Pittsburgh coal in western Virginia was produced around 1852 from a mine near the present city of Fairmont. Production and marketing success of the field increased, and in 1901 the Fairmont Coal Company was formed, later to become the Consolidation Coal Company.

West Virginia's southern coal fields were not opened until about 1870, though they were known to exist much earlier. One of the major southern coal fields was the Flat Top-Pocahontas Field, located primarily in Mercer and McDowell counties. The Flat Top Field first shipped coal in 1883 and grew quickly from that time. Individual mining operations were consolidated into large companies, and Pocahontas Fuel Company, organized in 1907, soon dominated the other companies in McDowell County.

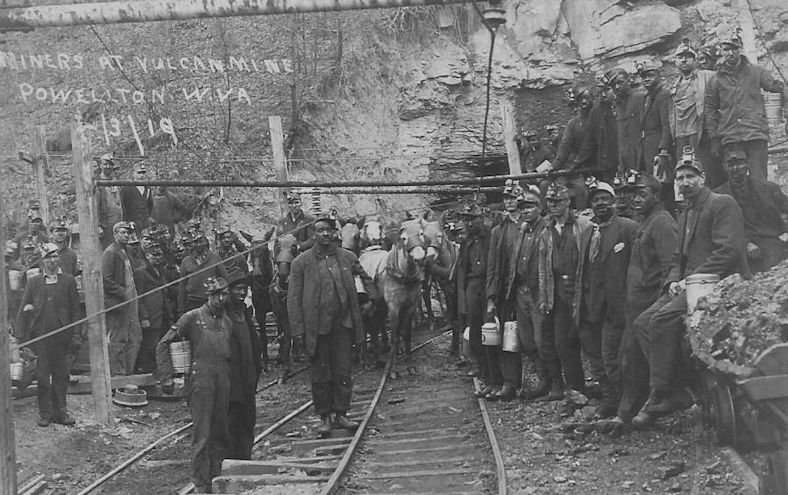

On March 12, 1883, the first carload of coal was transported from Pocahontas in Tazewell County, Virginia, on the Norfolk and Western Railway. This new railroad opened a gateway to the untapped coalfields of southwestern West Virginia, precipitating a dramatic population increase. Virtually overnight, new towns were created as the region was transformed from an agricultural to industrial economy. With the lure of good wages and inexpensive housing, thousands of European immigrants rushed into southern West Virginia. In addition, a large number of African Americans migrated from the southern states. The McDowell County black population alone increased from 0.1 percent in 1880 to 30.7 percent in 1910.

In 1888, Fayette County became the first county in West Virginia to produce more than a million tons of coal in one year, while the total amount of coal production for the entire state for that year was 5,498,800 tons. Just slightly less than 1/5 of the all the coal produced in West Virginia during 1888 was coming from mines located in Fayette County, most of them located deep within in the New River Gorge along the Chesapeake & Ohio mainline.

Many of the coal fields, such as the Kanawha, New River, Winding Gulf, Logan, and Greenbrier, owed their success to the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway. As the railway expanded its lines, coal became more available for marketing and the coal fields prospered. The Logan Field, lying in Logan and Wyoming counties, did not develop until 1904, when the railway finally reached the fields. Soon Logan became the largest coal-producing county in the State, dominated by the Island Creek Coal Company.

Between 1890 and 1912, West Virginia had a higher mine death rate than any other state. In fact, West Virginia is the site of the worst coal mining disaster to date. With the Monongah Mine disaster of Monongah, West Virginia on December 6, 1907. This explosion was caused by the ignition of methane gas, which in turn ignited coal dust. The lives of 362 men were lost in the underground explosion. This disaster caused the United States Congress to create the U.S. Bureau of Mines to regulate mine safety.

To combat the low pay and poor working conditions of the mining industryt he United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) was formed in Columbus, Ohio, in 1890. In its first ten years, the UMWA successfully organized miners in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois. Attempts to organize West Virginia failed in 1892, 1894, 1895, and 1897. In 1902, the UMWA finally achieved some recognition in the Kanawha-New River Coalfield, its first success in West Virginia. Following the union successes, coal operators had formed the Kanawha County Coal Operators Association in 1903, the first such organization in the state. It hired private detectives from the Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency in Bluefield as mine guards to harass union organizers. Due to these threats, the UMWA discouraged organizers from working in southern West Virginia.

By 1912, the union had lost control of much of the Kanawha- New River Coalfield. That year, UMWA miners on Paint Creek in Kanawha County demanded wages equal to those of other area mines. The operators rejected the wage increase and miners walked off the job on April 18, beginning one of the most violent strikes in the nation's history. Miners along nearby Cabin Creek, having previously lost their union, joined the Paint Creek strikers. When the strike began, operators brought in mine guards from the Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency to evict miners and their families from company houses. The evicted miners set up tent colonies and lived in other makeshift housing. The mine guards' primary responsibility was to break the strike by making the lives of the miners as uncomfortable as possible.

While unsuccessful, the Paint Creek-Cabin Creek strike produced a number of labor leaders who would play prominent roles in the years to come. Corrupt UMWA leaders were ousted and a group of young rank- and-file miners were elected. In November 1916, Frank Keeney was chosen president of UMWA District 17, and Fred Mooney was chosen secretary-treasurer. Following the Paint Creek-Cabin Creek strike, the coalfields were relatively peaceful for nearly six years. U.S. entry into World War I in 1917 sparked a boom in the coal industry, increasing wages. However, the end of the war resulted in a national recession. Coal operators laid off miners and attempted to reduce wages to pre-war levels.

In response to the 1912-13 strike, coal operators' associations in southern West Virginia had strengthened their system for combating labor. By 1919, the largest non-unionized coal region in the eastern United States consisted of Logan and Mingo counties. The UMWA targeted southwestern West Virginia as its top priority. The Logan Coal Operators Association paid Logan County Sheriff Don Chafin to keep union organizers out of the area. Chafin and his deputies harassed, beat, and arrested those suspected of participating in labor meetings. He hired a small army of additional deputies, paid directly by the association.

1920 brought the "Battle of the Tug" between union miners and mine guards. Non-union miners in Mingo County went on strike in the spring of 1920 and called for assistance from the District 17 office in Charleston. On May 6, Fred Mooney and Bill Blizzard, one of the leaders of the 1912-13 strike, spoke to around 3,000 miners at Matewan. Over the next two weeks, about half that number joined the UMWA. On May 19, twelve Baldwin-Felts detectives arrived in Matewan. Families of miners who had joined the union were evicted from their company-owned houses. The town's chief of police, Sid Hatfield, encouraged Matewan residents to arm themselves. Gunfire erupted when Albert and Lee Felts attempted to arrest Hatfield. At the end of the battle, seven detectives and four townspeople lay dead, including Mayor C. C. Testerman.

On August 24, 1921,approximately 5,000 men marched across Lens Creek Mountain. The miners wore red bandanas, which earned them the nickname, "red necks." In Logan County, Don Chafin mobilized an army of deputies, mine guards, store clerks, and state police. Meanwhile, after a request by Governor Morgan for federal troops, President Harding dispatched World War I hero Henry Bandholtz to Charleston to survey the situation. On the 26th, Bandholtz and the governor met with Keeney and Mooney and explained that if the march continued, the miners and UMWA leaders could be charged with treason. That afternoon, Keeney met a majority of the miners at a ballfield in Madison and instructed them to turn back. As a result, some of the miners ended their march. However, two factors led many to continue. First, special trains promised by Keeney to transport the miners back to Kanawha County were late in arriving. Second, the state police raided a group of miners at Sharples on the night of the 27th, killing two. In response, many miners began marching toward Sharples, just across the Logan County line.

The town of Logan was protected by a natural barrier, Blair Mountain, located south of Sharples. Chafin's forces, now under the command of Colonel William Eubank of the National Guard, took positions on the crest of Blair Mountain as the miners assembled in the town of Blair, near the bottom of the mountain. On the 28th, the marchers took their first prisoners, four Logan County deputies and the son of another deputy. On the evening of the 30th, Baptist minister James E. Wilburn organized a small armed company to support the miners. On the 31st, Wilburn's men shot and killed three of Chafin's deputies, including John Gore, the father of one of the men captured previously. During the skirmish, a deputy killed one of Wilburn's followers, Eli Kemp. Over the next three days, there was intense fighting as Eubank's troops brought in planes to drop bombs.

On September 1, President Harding finally sent federal troops from Fort Thomas, Kentucky. War hero Billy Mitchell led an air squadron from Langley Field near Washington, D.C. The squadron set up headquarters in a vacant field in the present Kanawha City section of Charleston. Several planes did not make it, crashing in such distant places as Nicholas County, Raleigh County, and southwestern Virginia, and military air power played no important part in the battle. On the 3rd, the first federal troops arrived at Jeffrey, Sharples, Blair, and Logan. Confronted with the possibility of fighting against U.S. troops, most of the miners surrendered. Some of the miners on Blair Mountain continued fighting until the 4th, at which time virtually all surrendered or returned to their homes. During the fighting, at least twelve miners and four men from Chafin's army were killed.

Those who surrendered were placed on trains and sent home. However, those perceived as leaders were to be held accountable for the actions of all the miners. Special grand juries handed down 1,217 indictments, including 325 for murder and 24 for treason against the state. The only treason conviction was against Walter Allen, who skipped bail and was never captured. The most prominent treason trial was that of Bill Blizzard, considered by authorities to be the "general" of the miners' army. In a change of venue, Blizzard's trial was held in the Jefferson County Courthouse in Charles Town, the same building in which John Brown had been convicted of treason in 1859. After several trials in different locations, all charges against Blizzard were dropped. Keeney and Mooney were also acquitted of murder charges. James E. Wilburn and his son were convicted of murdering the Logan County deputies. Both were pardoned by Governor Howard Gore after serving only three years of their eleven-year sentences.

The defeat of the miners at Blair Mountain temporarily ended the UMWA's organizing efforts in the southern coalfields. By 1924, UMWA membership in the state had dropped by about one-half of its total in 1921. Both Keeney and Mooney were forced out of the union, while Blizzard remained a strong force in District 17 until being ousted in the 1950s. In 1933, the National Industrial Recovery Act protected the rights of unions and allowed for the rapid organization of the southern coalfields.

Coal Company Owned Miners' Homes - Bream, WV

Eccles No.3 - New River Collieries Co.

Monongah Mine - Monongah, WV 1906

American Coal Co. McComas, WV

Indian Ridge Mine -Crumpler, WV

Company housing - Scott's Run, Cassville, Monongalia County, WV 1935

Lake Superior Coal Co. - Superior, WV

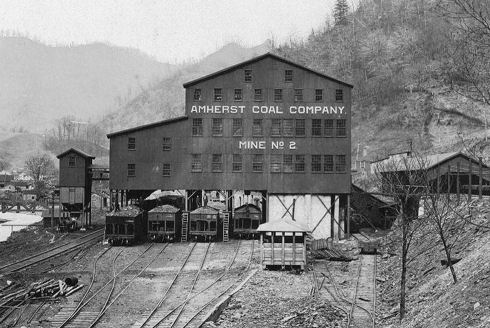

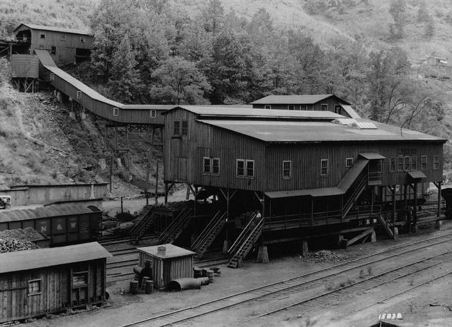

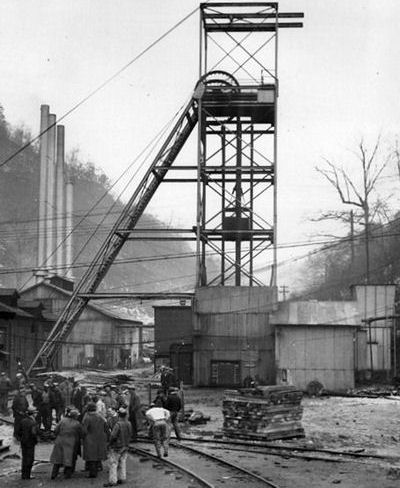

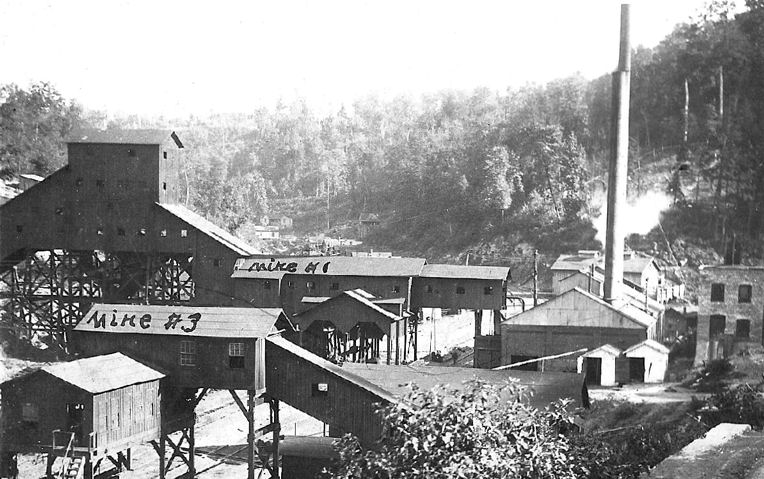

Amherst Coal Co. Mine No.1 - Logan Co. WV

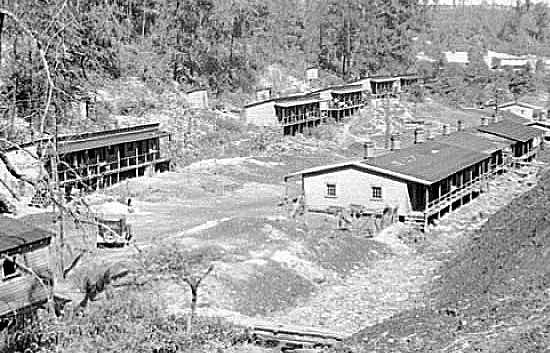

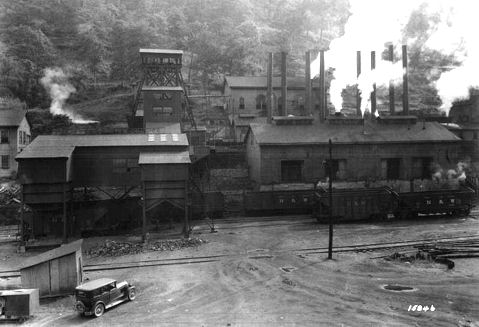

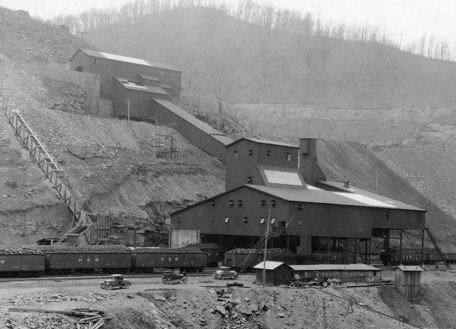

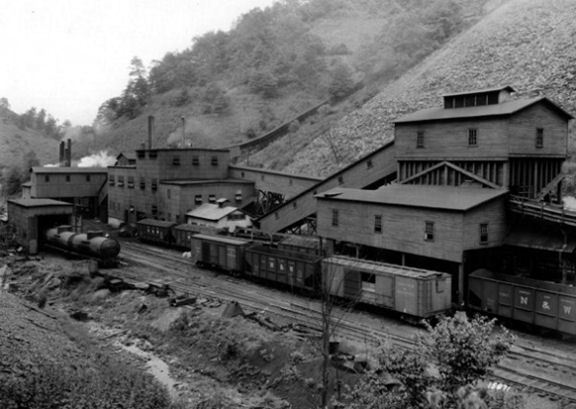

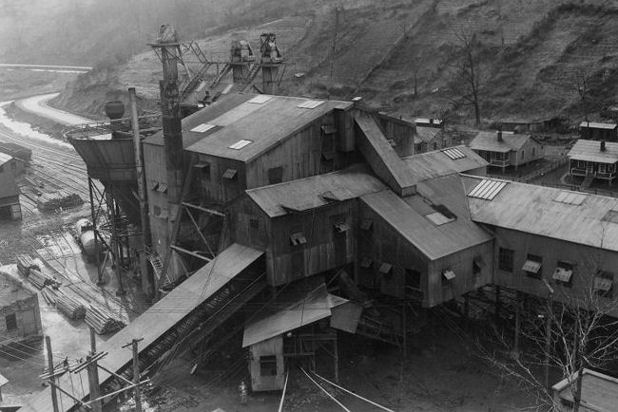

Amherst Coal Co. Mine No.2 - Logan Co. WV

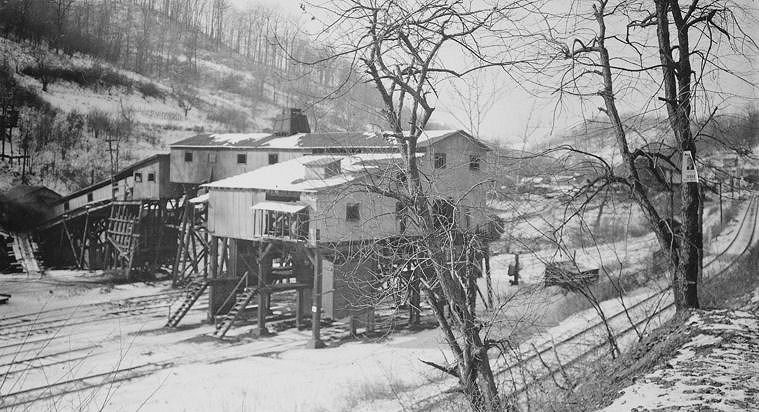

Amherst Coal Co. Mine No.2 - Logan Co. WV

Amherst Coal Co. Mine No.2 - Logan Co. WV

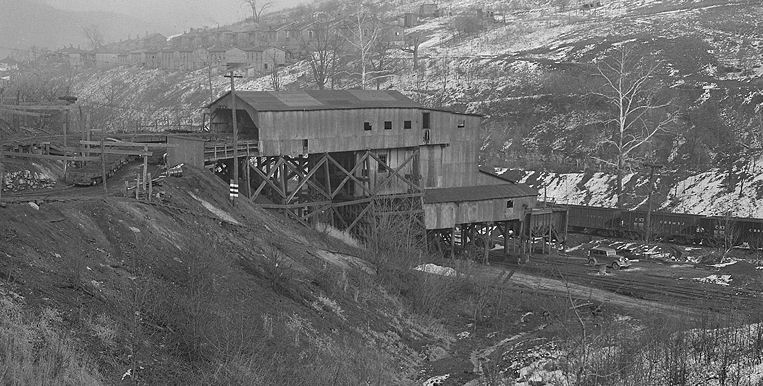

Amherst Coal Co. Mine No.2 - Logan Co. WV

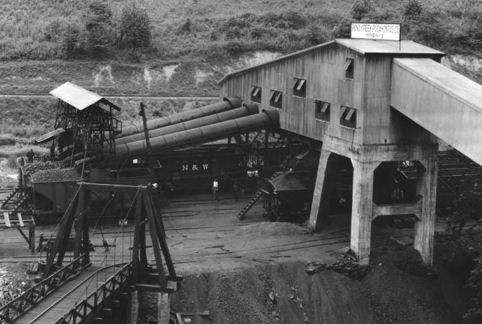

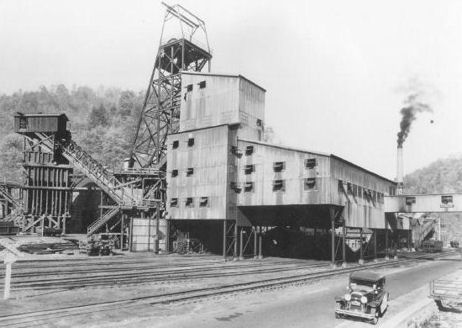

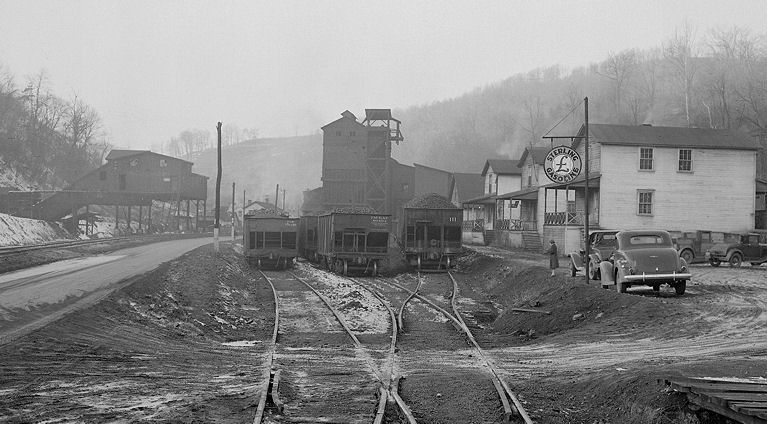

Pond Creek Pocahontas Coal Co. - Bartley, WV - 1933

Pond Creek Pocahontas Co. Mine No.3 - Bartley, VW

Pocahontas Fuel Co. Mine - Yukon, WV

United Pocahontas Coal Co. - Crumpler, McDowell Co. WV

Williams Pocahontas Coal Co. - War, WV 1931

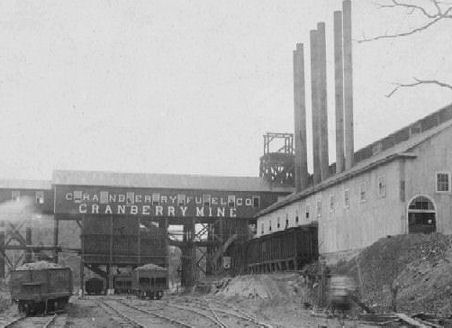

Cranberry Fuel Co. Cranberry Mine - Cranberry, WV

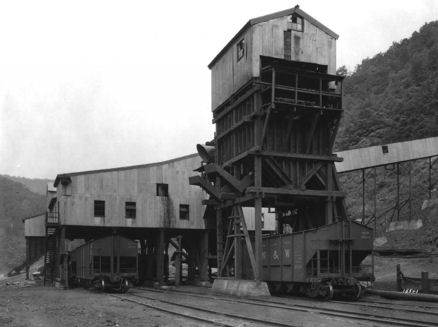

Pocahontas Corp. Tipple - Faraday, WV 1929

Unidentified Mine - Matewan, WV

McDowell Coal & Coke Co. - McDowell, WV 1931

Gay Mining Co. - Gilbert, WV 1944

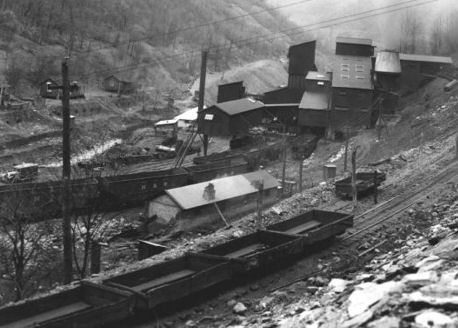

Crozer Coal Co. - Elkhorn, WV 1930

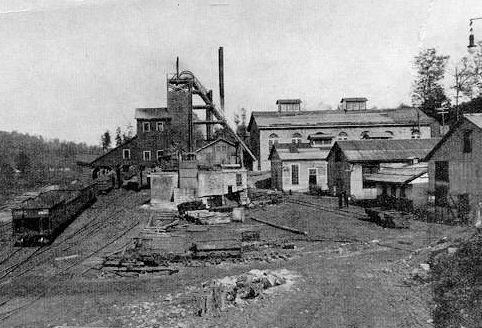

Unidentified West Virginia mine

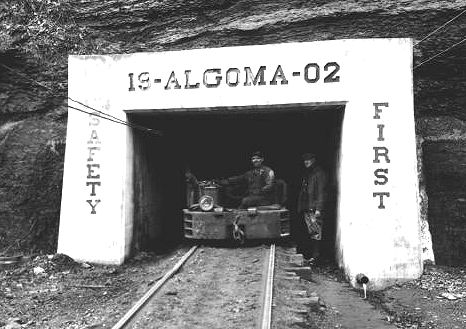

Algoma Coal Co. - Algoma, McDowell County, WV

Algoma Coal Co. - Algoma, McDowell County, WV

Coalwood Tipple seen from the aerial tram - Coalwood, WV

Consolidation Coal Company No.1 tipple - Coalwood., WV

Unidentified mine - Eccles, Raleigh County, WV

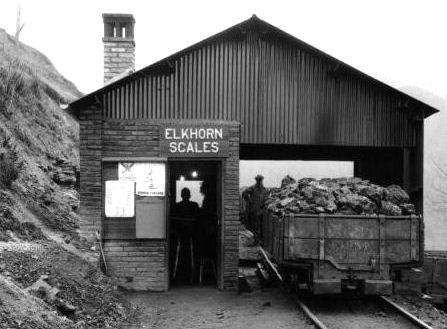

Elkhorn Colliery Scale House - Maybeury, WV

Sagamore Tipple - McComas, WV

Winding Gulf Collieries No. 3 - Davy, WV

Eastern Coal Co. - Premier, West Virginia

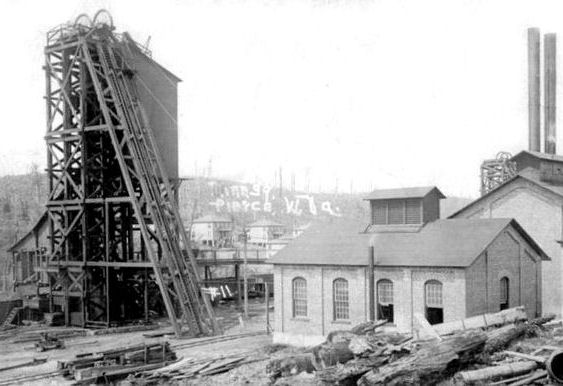

Mine No. 39 Pierce, WV

Ennis Coal Company - Hiawatha, WV

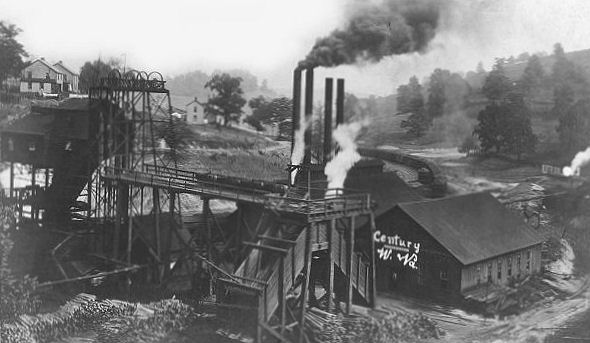

Coal mine - Century, WV 1911

Chapin, WV

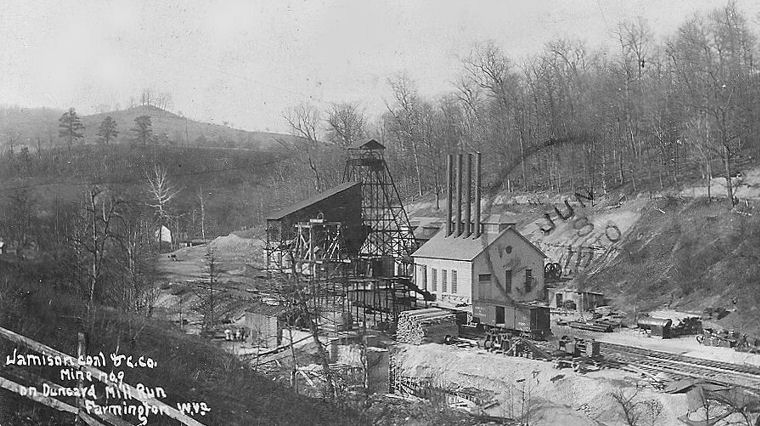

Jamison Coal & Coke Co. No. 8 Mine - Farmington, WV

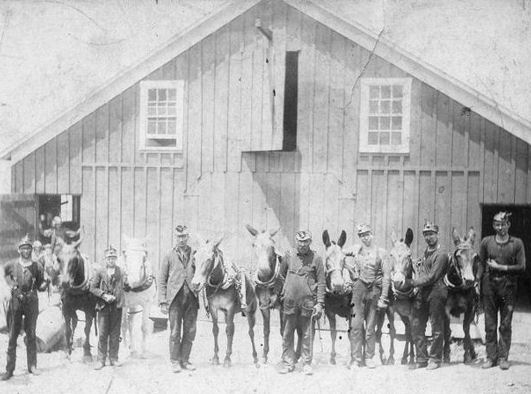

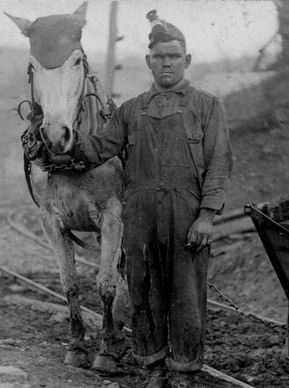

Miners & Mules - Junior, Randolph County, WV

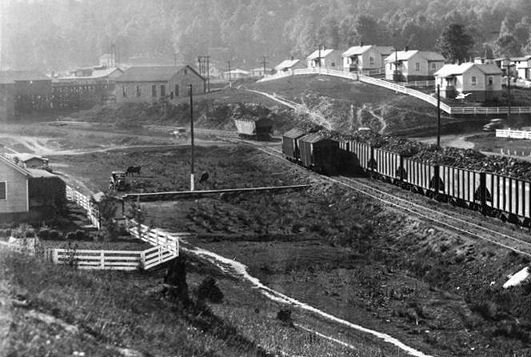

Richard Mine - Richard, Monongalia County, WV

White Oak Coal Company's Cranberry No. 3 Mine - Raleigh County, WV

Monongah, WV Miner

Bartley No. 1 Mine - Bartley, WV

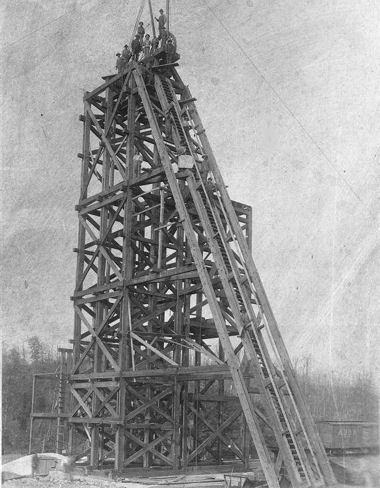

Building the headframe of Mine No. 39, Pierce, WV

Coal Miner - Monroe County, WV

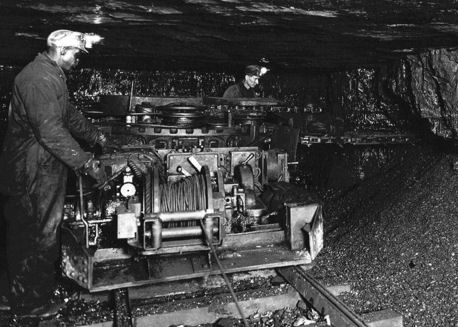

Winifrede Coal Seam - Winifrede, Kanawha County, WV.

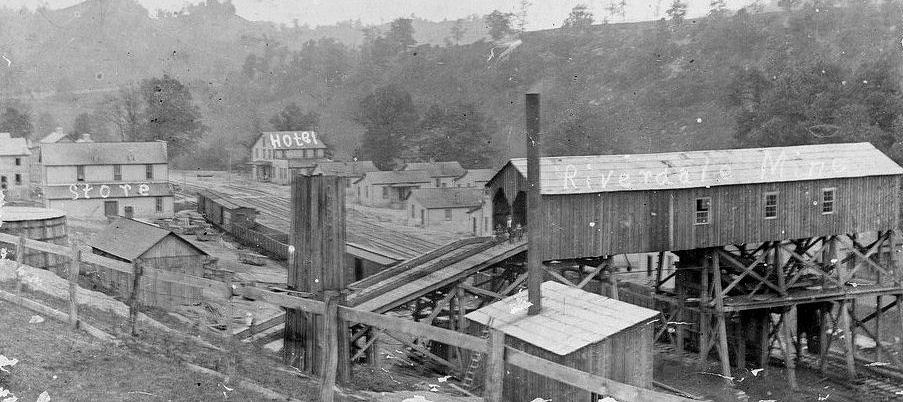

Consolidation Coal Co. Riverdale Mine Near Shinnston, Harrison County, WV

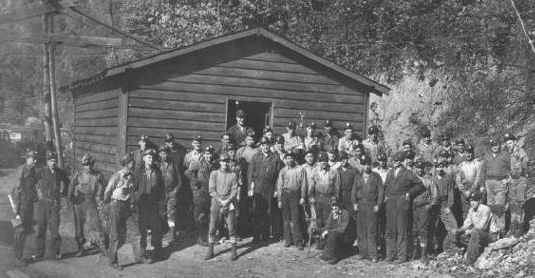

Waiting for their shift - Capels, McDowell County WV

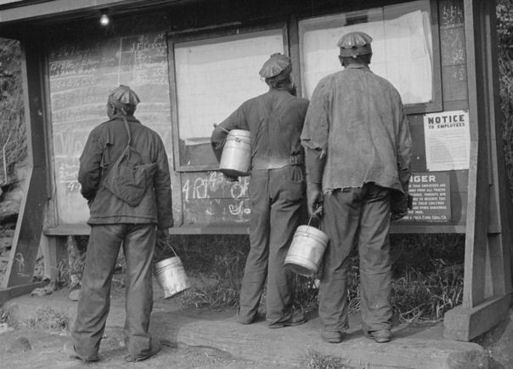

Checking the board - Capels, McDowell County, WV

End of their shift - Capels, McDowell County WV

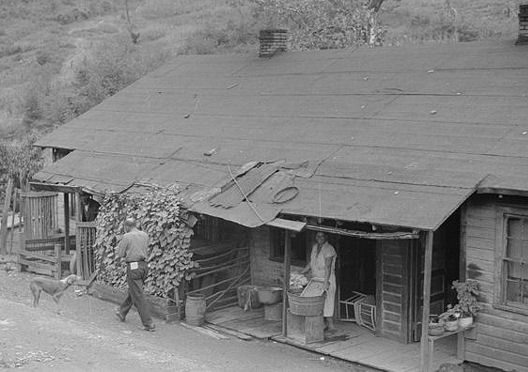

Miner's Home - Chaplin, WV

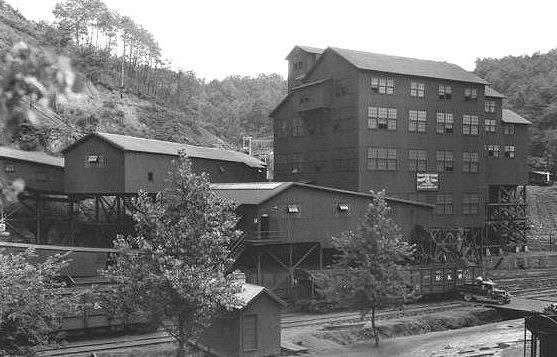

Raleigh Coal & Coke Company Tipple No. 3 - Raleigh, WV

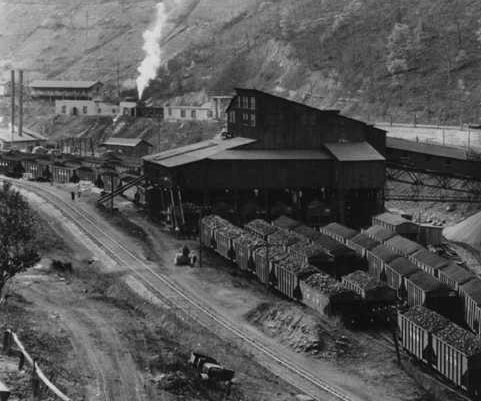

Island Creek Coal Co. Mine No. 14 - Logan County, WV

Island Creek Coal Co. Mine No. 22 - Logan County, WV

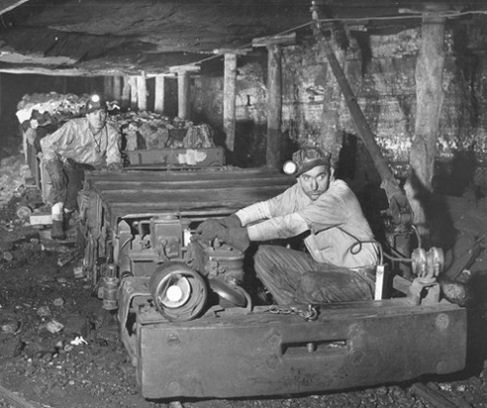

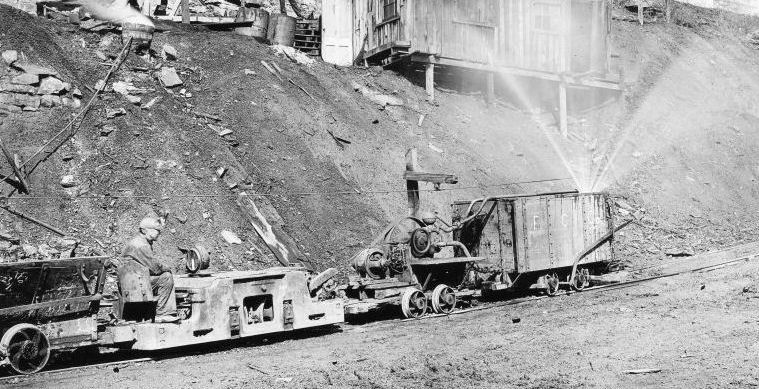

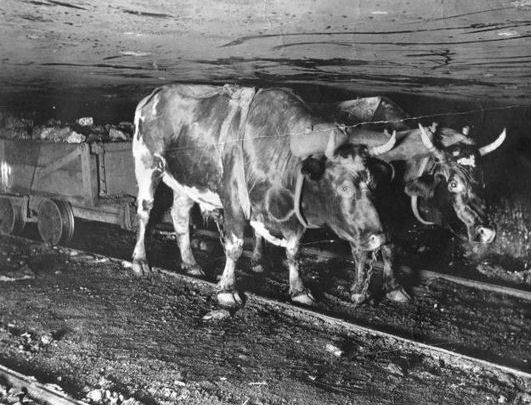

Oxen pulling coal car in unidentified West Virginia mine

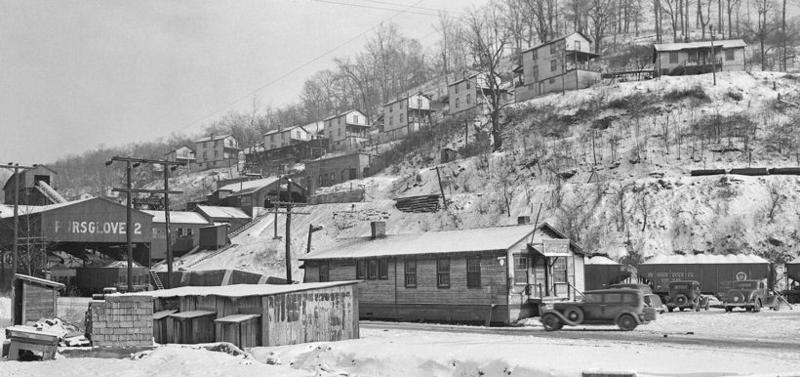

Pursglove No.2 Mine - Scott's Run, West Virginia

Brown Mine - Brown, West Virginia

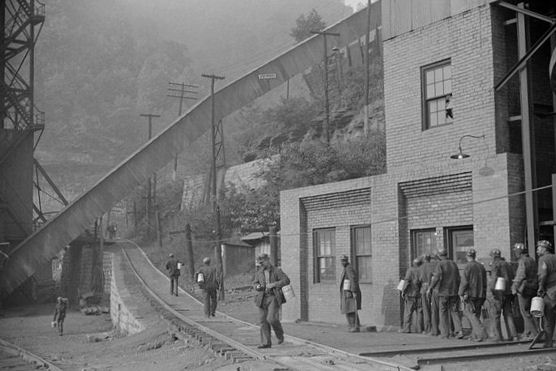

Starting shift - Maidesville, WV

West Virginia Coal Miners

Winding Gulf Coal Co. Mine - near Charleston, WV

Mine Tipple - Jere, Scott's Run, WV

Cassville Mine Tipple - Scott's Run, WV

Chaplin Hill Mine Tipple - Scott's Run, WV

Pursglove Mines Nos. 3 & 4 - Scott's Run, WV