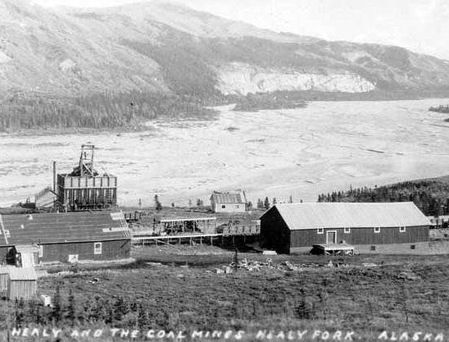

ALASKA MINES

Working the beach sands - Nome, Alaska

Placer Mining - Alaska

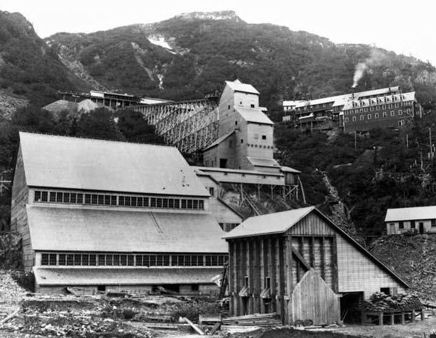

Perseverence Quartz Mine & Mill - Silver Bow Basin - Juneau, Alaska

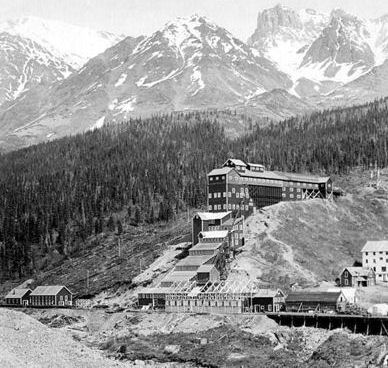

Eastern Alaska Mining & Milling Co. - Silver Bow Basin, Alaska

The Russians had been aware of the presence of gold in their territory of Alaska. In 1849 gold was found near the Russian River and reportedly other places on the Kenai Peninsula. In 1861, gold was discovered on Telegraph Creek near the settlement of Wrangell. The Russians were concerned about a rush of foreign prospectors into a territory they could barely hold claim to and were embroiled in conflicts elsewhere. This, in part, led to the sale of Alaska to the United States in 1867.

It is difficult to separate the Yukon and Alaskan Gold Rushes since the path to one went through the other. The development of Alaska is tied to the gold rush in the Yukon Territory of Canada and the Alaskan Gold Rush.

The Klondike Gold Rush, also called the Yukon Gold Rush, the Alaska Gold Rush and the Last Great Gold Rush, was an attempt by an estimated 100,000 people to travel to the Klondike region of the Yukon in north-western Canada between 1897 and 1899 in the hope of successfully prospecting for gold. Gold was discovered in large quantities in the Klondike on 16 August 1896 and, when news of the finds reached Seattle and San Francisco in July 1897, it triggered a "stampede" of would-be prospectors to the gold creeks. The journey to the Klondike was arduous and involved travelling long distances and crossing difficult mountain passes, frequently while carrying heavy loads. Some miners discovered very rich deposits of gold and became immensely wealthy. However, the majority arrived after the best of the gold fields had been claimed and only around 4,000 miners ultimately struck gold. The Klondike Gold Rush ended in 1899, after gold was discovered in Nome, prompting an exodus from the Klondike. The Klondike Gold Rush was immortalized by the photographs of the prospectors ascending the Chilkoot Pass, by books like The Call of the Wild, and films such as The Gold Rush.

Prospectors had begun to mine gold in the Yukon from the 1880s onwards. When the rich deposits of gold were initially discovered along the Klondike River in 1896, it was met with great local excitement. The remoteness of the region and the extreme winter climate prevented news from reaching the outside world until the following year. The initial Klondike stampede was triggered by the arrival of over US$1,139,000 (equivalent to US$1,000 million in 2010 terms) in gold at the north-western American ports in July 1897. Newspaper reports of the gold and the successful miners fuelled a nation-wide hysteria: many left their jobs and set off for the Klondike, hoping to make a fortune as miners. These would-be prospectors were joined by businessmen, outfitters, writers and photographers. Reaching the gold fields was challenging. The majority of prospectors landed at the ports of Dyea and Skagway in South-east Alaska. They could then take either the Chilkoot or the White Pass trails to the Yukon River and, from there, sail down-stream to the Klondike in self-made boats. Each prospector was required to bring a year's supply of food with them by the Canadian authorities and many had to carry this ton of supplies in stages over the passes. The advent of winter and thereby freezing of rivers meant that most prospectors did not arrive in the goldfields until summer 1898. Only between 30,000 and 40,000 of the stampeders successfully arrived in the Klondike.

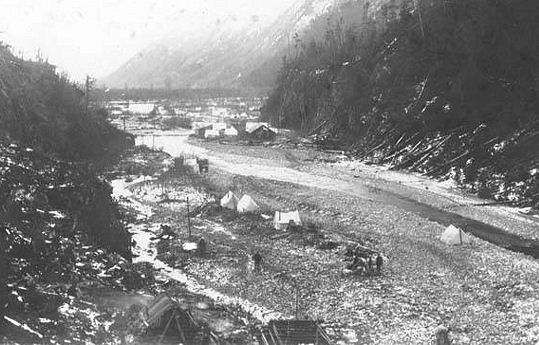

It was not easy to mine for gold in the Klondike as the gold was distributed in an uneven, mostly unpredictable manner and the permafrost made digging and working the ore difficult and costly. Prospectors could lodge mining claims relatively easily under Canadian law, but most of the best gold creeks had been staked out by early 1898, leaving little good land for the main wave of stampeders. Some miners bought and sold claims, building up huge investments. Boom towns sprang up along the routes, especially the Dyea and Skagway route, to accommodate the influx of prospectors. Dawson City was founded in the Klondike at the heart of the gold creeks. From a population of 500 in 1896, by spring 1898, the hastily constructed wooden town housed around 30,000 people. Poorly built, isolated and located on a mud flat, Dawson City had poor sanitary standards and suffered from epidemics and fires. The wealthiest prospectors lived a life of conspicuous consumption, gambling and drinking heavily in the town's saloons and dancing halls, despite the high prices of almost everything. The Native Hän people, who had lived along the Klondike before the discovery of gold, suffered extensively during the rush, being moved into a reserve to make way for the stampeders; many of the Hän died as a result.

Some prospectors, unable to make a living in the Klondike, started to return home from the summer of 1898. The newspapers began to turn against the Klondike and the hysteria that had encouraged so many to travel there slowly waned. Dawson City was rebuilt following a serious fire in April 1899, becoming more sedate and conservative. When news arrived in the summer of 1899 that gold had been discovered in Nome in west Alaska, many prospectors left the Klondike for the new goldfields, marking the end of the Klondike Gold Rush. The boom towns in the Klondike declined and the population of Dawson City fell away. Heavier equipment was brought in to mine the remaining gold reserves but, despite this, production diminished after 1903. Nonetheless, an estimated total of 1,250,000 pounds of gold had been taken from the Klondike area by 2005.

Chilkoot Pass, AK

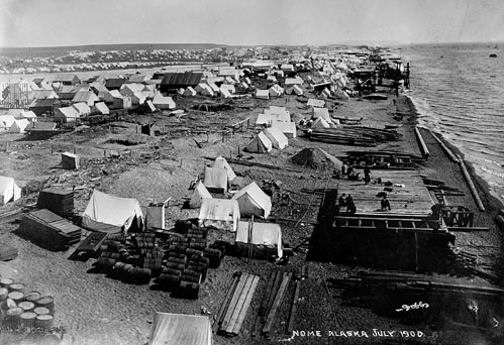

Nome Beach, AK 1900

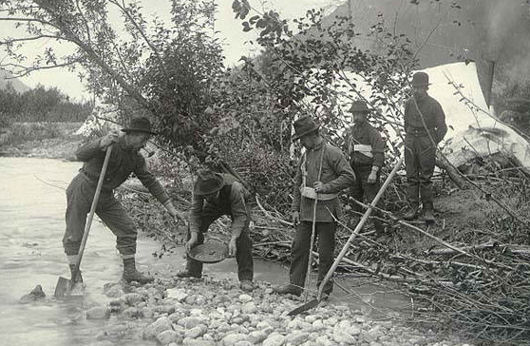

Gold Panning - AK

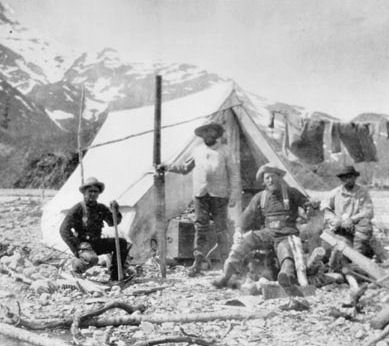

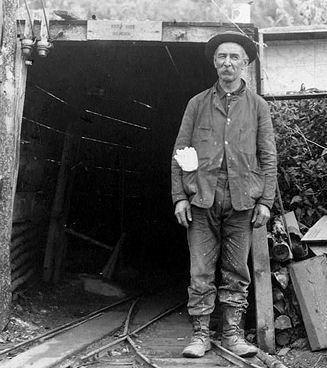

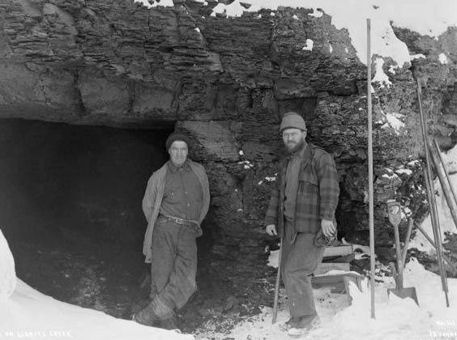

Miners - Wrangell-St. Elias, AK 1898

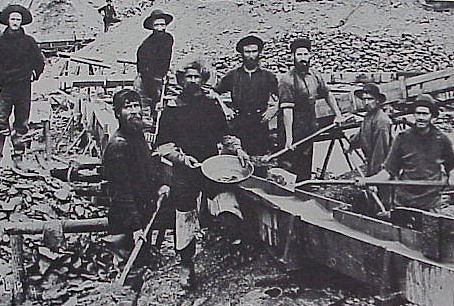

Alaskan Miners

Nome Beach, AK 1900

Tent settlement - Canyon City, Dyea River

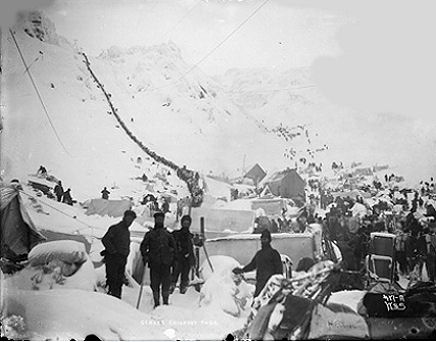

Chilkoot Trail, Alaska 1897

Treadwell Gold Mining Co. - Douglas Island, Juneau, AK

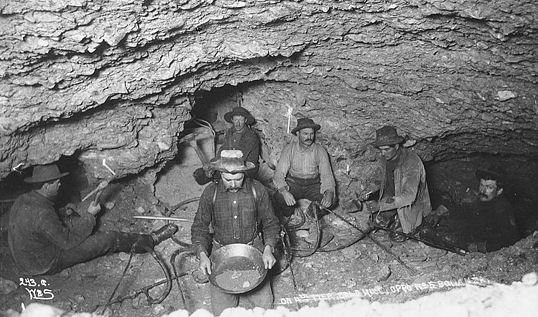

Treadwell Mine underground

Gold mining sluice - Alaska

Gold Panning - AK

Gold prospector - Seward, AK

Rhoades-Hall Mine - AK

Kennecott Copper Co. Bonanza Mine - Alaska

Miners During the Gold Rush - Alaska - 1900

Gold prospectors - Alaska

Washing gold - Alaska

Gold Hill, AK - 1898

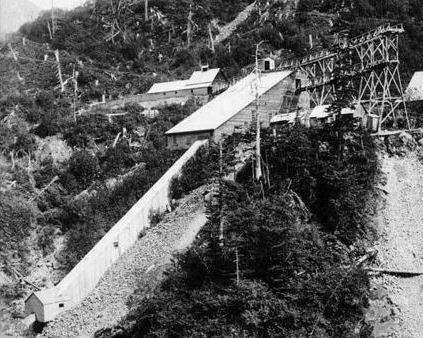

Ellamar Mine - Valdez-Cordova Borough, Prince William Sound District, AK

Russian explorers discovered copper on the Kasaan Peninsula of Prince of Wales Island in southeastern Alaska about 1865. Mining began in the period 1895-1900, and continued until shortly after World War I. Copper is present as chalcopyrite, occurring with magnetite, pyrite, garnet, epidote, diopside, and hornblende, in replacement deposits in greenstone. Gold and silver were recovered as byproducts.

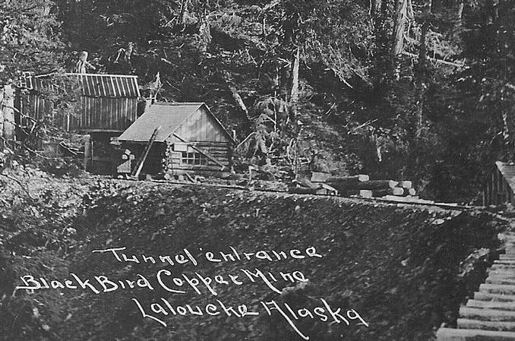

Copper was discovered at Prince William Sound in 1897. Deposits were associated with pillow basalts alterered to greenstone. The basalts are interbedded with slate and greywacke, faulted, and intruded by granitic rocks. The principal mines were the Beatson-Bonanza mine at Latouche and the Ellamar mine, which accounted for 96% of the copper produced. Other mines were the Midas mine near Valdez, the Threeman mine, and the Fidalgo-Alaska mine at Port Fidalgo, Alaska. Mining began in 1900, and continued until 1930. Total production was 96,000 tons of copper.

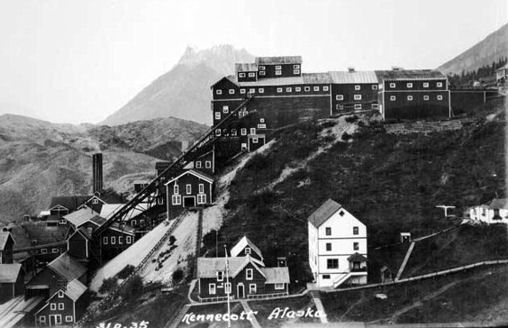

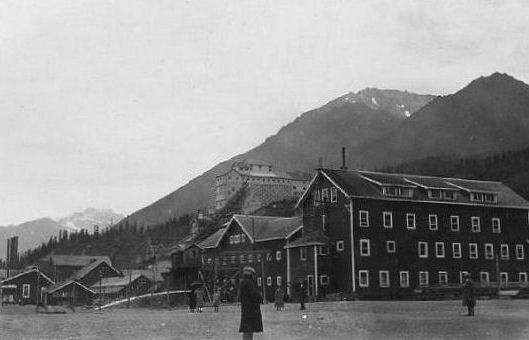

Historically, the largest copper mining district in Alaska was the Nizina district, the principal mines of which (Erie mine, Jumbo mine, Bonanza mine, Mother Lode mine, and Green Butte mine) were at Kennecott, Alaska, four miles north of McCarthy. The copper is present as chalcocite in veins and irregular replacements in the Triassic Chitistone Limestone. Some silver was also produced as a byproduct. The mine at Kennecott gave rise to Kennecott Copper Corporation, which outlasted the mine, and is still a major mining company. The deposit was discovered in 1900, and once a railroad connection was built, the mine operated from 1911 to 1938, after which Kennecott became a ghost town.

The Ketchikan mining district comprises Cleveland Peninsula, the mainland between Portland and Behm Canals, the important islands of Prince of Wales and Revillagedo (on which Ketchikan is situated), and contiguous islets.

The only copper-producing mines of southeastern Alaska are in this district. Before 1905 the output, with by-products of gold and silver, metal values aggregated about $200,000. Extended mining operations were then initiated and the values realized from six mines were $339,000 in 1900, and from ten mines $920,000 in 1906. The average value per ton produced for two years was $10.80, and total estimated output was $840,000 in 1907. The decrease in the production for 1907 was due to the general depression in the copper trade throughout the world, which rendered the mining of low-grade ores unprofitable in Alaska, as elsewhere. The general richness of the Alaskan copper mines, however, stimulated capitalists to extended operations in their development throughout the district. In all Alaska fifteen mines made shipments of copper in 1907 as against fourteen in 1906, ten being in southeastern Alaska, and there was increased activity in prospecting. Naturally the depression of the autumn of 1907 temporarily closed many mines.

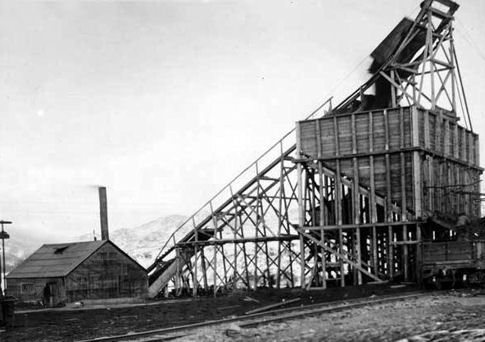

Kennecott Mine - Kennecott, Nizina District, AK

Copper mine - Latouche Island, Prince William Sound, AK

Kennecott Copper mine - Alaska

Beatson Mine - Valdez-Cordova Borough, Prince William Sound District, AK

On August 16, 1896, an American prospector named George Carmack, his Tagish wife Kate Carmack, her brother Skookum Jim and their nephew Dawson Charlie were travelling south of the Klondike River. Following a suggestion from Robert Henderson, another prospector, they began looking for gold on Bonanza Creek, then called Rabbit Creek, one of the Klondike's tributaries. It is not clear who actually discovered the gold: Carmack later claimed he found it, while Skookum Jim and Dawson Charlie argued that Jim did. In any event, gold was present along the river in huge quantities

Carmack measured out four claims, strips of ground that could later be legally mined by the owner, along the river, including two for himself, one as his normal claim, the second as a reward for having discovered the gold, and one each for Jim and Charlie. Jim later stated that Carmack's extra claim was really his own and had only been staked in Carmack's name because the group felt that others would be reluctant to recognize a claim made by an Indian. The claims were registered next day at the police post at the mouth of the Fortymile River and news spread rapidly from there to other mining camps in the Yukon River valley.

By the end of August, all of Bonanza Creek had been claimed by miners. A prospector then advanced up into one of the creeks feeding into Bonanza, later to be named Eldorado Creek. He discovered new sources of gold there, which would prove to be even richer than those on Bonanza Creek Claims began to be sold between miners and speculators for considerable sums. Just before Christmas, word of the gold finds finally reached Circle City, the nearest large settlement in Alaska. Despite the winter, many prospectors immediately left for the Yukon by dog-sled, eager to reach the region before the best claims were taken.

The outside world was still largely unaware of the news and although Canadian officials had managed to send a message to their superiors in Ottawa about the gold finds and the rapidly increasing influx of prospectors, the government did not give the matter much attention, apparently due to administrative delays. The ice prevented river traffic over the winter and it was not until June 1897 that the first boats left the area, carrying the freshly mined gold and the full story of the discoveries.

The Klondike stampede was an attempt by an estimated 100,000 people to reach the Klondike goldfields, of whom only around 30,000 to 40,000 eventually did. It formed the height of the Klondike gold rush from the summer of 1897 until the summer of 1898. It began on 15 July 1897 in San Francisco and two days later in Seattle, when the first of the early prospectors returned from the Klondike, bringing with them large amounts of gold. The press reported that a total of $1,139,000 had been brought in by these ships, although this proved to be an underestimate. The migration caught so much attention that it was joined by would-be prospectors and also businessmen, outfitters, writers and photographers.

There was a huge, unresolved demand for gold across the developed world that the Klondike offered to fulfil and, for individuals, the region promised higher wages or financial security. Psychologically, the Klondike, as historian Pierre Berton describes, was "just far enough away to be romantic and just close enough to be accessible". Furthermore, the Pacific ports closest to the gold strikes were desperate to encourage trade and travel to the region. The mass journalism of the period promoted the event and the human interest stories that lay behind it. A worldwide publicity campaign engineered largely by Erastus Brainerd, a Seattle newspaper man, helped establish the city as the premier supply center and the departure point for the gold fields

Seattle and San Francisco competed fiercely for business during the rush, with Seattle winning the larger share of trade. Indeed, one of the first to join the gold rush was William D. Wood, the mayor of Seattle, who resigned and formed a company to transport prospectors to the Klondike. The publicity around the gold rush led to a flurry of branded goods being put onto the market. Clothing, equipment, food and medicines were all sold as "Klondike" goods, allegedly specifically designed for the north. Guidebooks of a more or less serious nature were published, giving advice about the routes, equipment, mining and capital necessary for the enterprise.

In the late 19th century, there were two established routes to the interior of the Yukon: either up the Yukon River by river boat from its delta in the Bering Sea or across land from the South-east Alaskan ports of Dyea and Skagway to the head of the Yukon River and then down the river by boat or canoe. Other routes were of a more improvised nature, based on old fur trader’s routes and routes for previous smaller gold rushes in Alaska or Canada. Travel in general was made difficult by both the geography and climate. The region was mountainous, and the rivers winding and sometimes impassable; the short summers could be hot, while from October to June, during the long winters, temperatures could drop to −50 °C and less.

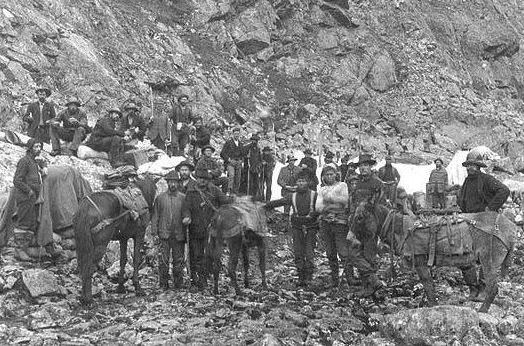

Aids for the travellers Shortly after the stampede began in 1897, the Canadian authorities had introduced rules requiring anyone entering Yukon Territory to bring with them a year's supply of food; typically this weighed around 1,150 pounds. By the time camping equipment, tools and other essentials were included, a typical traveller was transporting as much as a ton in weight. Unsurprisingly, the price of draft animals spiralled; at Dyea, even poor quality horses could sell for as much as $700 ($19,000 today), or be rented out for $40 ($1,100 today) a day.

From Seattle or San Francisco, prospectors could travel by sea up the coast to the ports of Alaska. The sudden increase in demand encouraged a range of vessels to be pressed into use to carry the gold-rush travellers and their cargo. Many dangerously unsafe vessels were put into service including older ships, paddlewheelers, fishing boats, barges and coal ships still full of coal dust.[ All were overloaded and many sank[ Prices increased sharply. At the start of the rush, a ticket from Seattle to the port of Dyea cost $40 ($1,100) for a cabin. Premiums of $100 ($2,700), however, were soon paid and the steamship companies hesitated to post their rates in advance since they could increase on a daily basis.

It was possible to sail all the way to the Klondike, first from Seattle across the northern Pacific to the Alaskan coast. From St. Michael, at the Yukon River delta, a river boat could then take the prospectors the rest of the way up the river to Dawson, often guided by one of the Native Koyukon people who lived near St. Michael. Although this all-water route was expensive and long, 4,700 miles in total, it had the attraction of speed and avoiding overland travel. In 1897, 1,800 travellers attempted this route but the vast majority were caught along the rivers when the region iced over in October. Only 43 successfully reached the Klondike before winter and of those 35 had to return, having thrown away their equipment en route to reach their destination in time. The remainder mostly found themselves stranded in isolated camps and settlements along the ice-covered rivers in desperate circumstances

Most of the prospectors landed at the South-east Alaskan towns of Dyea and Skagway, both located at the head of the natural Lynn Canal. From there, they would need to travel 30 miles over the mountain ranges into Canada's Yukon Territory, and then down the river network to the Klondike itself. Along the trails, tent camps sprung up where prospectors had to stop, either to eat or sleep or at obstacles such as the icy lakes at the head of the Yukon.

Those who landed at Skagway needed to make their way over the White Pass before cutting across to Bennett Lake. Although the trail began gently enough, it progressed over several mountains with narrow paths, only 2 feet wide in some places, with the wider parts covered with boulders and sharp rocks. In these conditions, the horses that were used to transport goods died in huge numbers, giving part of the pass the name Dead Horse Gulch, and the route the informal name of Dead Horse Trail. The volumes of travelers and the wet weather rapidly made the trail impassable and, by late 1897, it was officially closed, leaving around 5,000 stranded in Skagway.

An alternative toll road suitable for wagons was eventually constructed and this, combined with colder weather that froze the muddy ground, allowed the White Pass to reopen, and prospectors began to make their difficult way into Canada. Moving supplies and equipment over the pass, however, was no easy task. Most divided up their belongings into 65 pounds packages that could be carried on a man's back, or heavier loads that could still be pulled by hand on a s[led. Ferrying their belongings forwards and walking back for more, a prospector would need about thirty round trips, a distance of at least 2,500 miles, before they had moved all of their supplies over the pass and to the end of the trail. Even using a heavy sled, a strong man would be covering 1,000 miles and need around 90 days to reach Lake Bennett.

Those who landed at Dyea traveled the Chilkoot Trail and crossed the Chilkoot Pass to reach Lake Lindemann, which fed into Lake Bennett at the head of the Yukon River. Chilkoot Pass was higher than the White Pass, but more used it: around 22,000 during the gold rush. The trail passed up through camps until it reached a flat ledge, just before the main ascent; beyond this point the route became too steep for animals to climb. This location was known as the Scales, and was where goods were weighed before travelers officially entered Canada. While the mountain pass could be climbed, the cold, the slow pace and weight of the equipment made the journey extremely arduous and it could take a day to climb the 1,000 feet of the pass. As on the White Pass trail, supplies needed to be broken down into smaller packages and carried in relay. Packers, prepared to carry supplies for cash, were available along the route but would charge up to $1 ($27) per lb on the later stages; many of these packers were Natives, members of the Tlingit people or, less commonly, the Tagish. Avalanches were common in the mountains and, on 3 April 1898, one claimed the lives of more than 60 people travelling over Chilkoot Pass.

Entrepreneurs began to provide solutions as the winter progressed. Steps were cut into the ice at the Chilkoot Pass which could be used for a daily fee, this 1,500 step staircase becoming known as the "Golden Steps". By December 1897, a tramway powered by a horse at the bottom, which walked in a circle pulling a wheel-mounted rope, had been built by Archie Burns to ferry packages up the final parts of the Chilkoot Pass. Five more tramways soon followed, one powered by a steam engine, charging between 8 and 30 cents ($2 and $8) per 1 pound. An aerial tramway was built in the spring of 1898, able to move 9 tons of goods an hour up to the summit.

At Lakes Bennett and Lindeman, the prospectors camped in order to build rafts or boats that would take them the final 500 miles down the Yukon to Dawson City in the spring. 7,124 boats of varying size and quality left in May 1898. By the time they left, the forests around the lakes had been largely cut down for timber. The river posed a new problem. Until Whitehorse, it was dangerous, with several rapids along the Miles Canyon through to the White Horse Rapids. After many boats were wrecked and several hundred people died, the North-West Mounted Police (NWMP, now the Royal Canadian Mounted Police) introduced safety rules, vetting the boats carefully and forbidding women and children to travel through the rapids, instead they had to walk around. Additional rules stated that any boat carrying passengers required a licensed pilot, typically costing $25 ($680), although some prospectors simply unpacked their boats, let them drift unmanned through the rapids with the intent of walking down to collect them on the other side of the rapids. During the summer, a horse-powered rail-tramway was built by Norman Macaulay, capable of carrying boats and equipment through the canyon at $25 ($680) a time, removing the need for prospectors to navigate the rapids.

There were a few more trails established during 1898 from South-east Alaska to the Yukon River. One was the Dalton trail: starting from Pyramid Harbour, close to Dyea, it went across the Chilkat Pass some miles west of Chilkoot and turned north to the Yukon River, a distance of about 350 miles. This was created by Jack Dalton as a summer route, intended for cattle and horses, and Dalton charged a toll of $250 ($6,800) for its use. The Takou route started from Juneau and went north-east to Teslin Lake. From here, it followed the river to the Yukon, where it met the Dyea and Skagway route at a point halfway to the Klondike. It meant dragging and poling canoes up-river and through mud together with crossing a 5,000 feet high mountain along a narrow trail. Finally, there was the Stikine route starting from the port of Wrangell further south-east of Skagway. This route went up the uneasy Stikine River to Glenora, the head of navigation. From Glenora, prospectors would have to carry their supplies 150 miles to Teslin Lake, a part of the Yukon River system.

Of the estimated 30,000 to 40,000 people who reached Dawson City during the gold rush, only around 15,000 to 20,000 finally became prospectors. Of these, no more than 4,000 struck gold and only a few hundred became rich. By the time that most of the stampeders arrived in 1898, the best creeks had all been claimed, either by the long-term miners in the region, or by the first arrivals of the year before. The Bonanza, Eldorado, Hunker and Dominion Creeks were all taken, with almost 10,000 claims recorded by the authorities by July 1898; a new prospector would have to look further afield to find a claim of his own.

Geologically, the region was permeated with veins of gold, forced to the surface by volcanic action and then worn away by the action of rivers and streams, leaving nuggets and gold dust. Some ores lay along the creek beds in lines of loose soil deposits, typically 15 feet to 30 feet beneath the surface. Others, formed by even older streams, lay along the hilltops; these deposits were called "bench gold". Finding the gold was challenging. Initially, miners had assumed that all the gold would be along the existing creeks, and it was not until late in 1897 that the hilltops began to be mined. Gold was also unevenly distributed in the areas where it was found, which made prediction of good mining sites even more uncertain. The only way to be certain that gold was present was to conduct exploratory digging.

Mining would begin with clearing the ground of vegetation and debris. Prospect holes were then dug into the ground, in an attempt to identify where the gold ore, or "paystreak", might be running. If these holes looked productive, proper digging could commence, aiming to proceed down to the bedrock, where the majority of the gold was found. The digging would be carefully monitored in case the operation needed to be shifted slightly to allow for changes in the flow of the creek over the year. In the sub-Arctic climate of the Klondike, a layer of hard permafrost lay only 6 feet below the surface. Traditionally, this had meant that mining in the region only occurred during the summer months, but the pressures of the gold rush made such a delay unacceptable. Late 19th century technology existed for dealing with this problem, including hydraulic mining and stripping, and large scale dredging, but this required heavier equipment than could be brought into the Klondi duher.

Instead, the miners relied on wood fires to soften the ground to a depth of about 14 inches and then removing the resulting gravel. The process was repeated until the gold was reached. In theory, no support of the shaft was necessary because of the permafrost although in practice sometimes the fire melted the permafrost and caused collapse. Such fires could produce noxious gases, which had to be removed by bellows or other tools. The resulting "dirt" brought out of the mines froze quickly in winter and could only be processed during the warmer summer months. An alternative, more efficient, approach called steam thawing was devised between 1897 and 1898; this used a furnace to pump steam directly into the surface of the ground, but required additional equipment and was not a widespread technique during the years of the Klondike gold rush.

In the summer, water would be used to sluice and pan the dirt, separating out the heavier gold from gravel. This required miners to construct sluice lines, which were sequences of wooden boxes 15 feet long, through which the dirt would be washed; up to 20 of these might be needed for each mining operation. The sluice lines in turn required lots of water, usually produced by creating a dam and ditches or crude pipes. "Bench gold" mining on the hill sides could not use sluice lines because running water could not be pumped up the hills. Instead, these mines used rockers, long boxes that moved back and forth like a cradle, again separating the heavier gold from the lighter dirt. Finally, the resulting gold dust could be exported out of the Klondike; exchanged for paper money at the rate of $16 ($430) per troy ounce through one of the major banks that opened in Dawson City, or simply used as money when dealing with local suppliers and traders.

The Klondike gold rush faltered over the winter of 1898–99. Communications had improved, and by 1899 telegraphy stretched from Skagway to Dawson, allowing instant international communication. In 1898, the White Pass and Yukon Route railway began to be built between Skagway and the head of navigation on the Yukon at Whitehorse; 35,000 men and tons of explosives were used for the construction. When it was completed in July 1900, the Chilkoot trail and its tramways was made obsolete.[286] Despite these improvements, other factors led to the conclusion of the stampede in 1899.

As early as the summer of 1898, many of the prospectors arriving in Dawson City had found themselves unable to make a living and had left for home. The wages of casual workers in Dawson, depressed by the number of destitute men in the town, had fallen to $100 ($2,700) a month by 1899. The world's newspapers began to turn against the Klondike gold rush. "Ah, go to the Klondike!" became a popular phrase to express disgust with an idea. Unsold, Klondike-branded goods had to be disposed of at special rates in Seattle.

Another factor was the change in Dawson City itself, which had developed throughout 1898, changing faster after the great fire of 1899, metamorphosing from a ramshackle, if wealthy, boom town into a more sedate, conservative municipality. More modern luxuries were introduced, including the "zinc bath tubs and pianos, billiard tables, Brussels carpets in the hotel dining rooms, menus printed in French and invitational balls" noted by historian Kathryn Winslow. The visiting Senator Jerry Lynch likened the newly paved streets with their smartly dressed inhabitants to the Strand in London. It was no longer as attractive a location for many prospectors, used to a wilder way of living. Even the formerly lawless town of Skagway had become a stable and respectable community by 1899.

The final trigger, however, was the discovery of gold elsewhere in Canada and Alaska, prompting a new stampede, this time away from the Klondike. In 1898 August gold had been found at Atlin Lake at the head of the Yukon River, generating a flurry of interest, but during the winter of 1898–99 much larger quantities were found at Nome at the mouth of the Yukon River. In 1899, a flood of prospectors from across the region left for Nome, 8,000 from Dawson alone during a single week in August. The Klondike gold rush was over and the Alaskan Gold Rush was on.

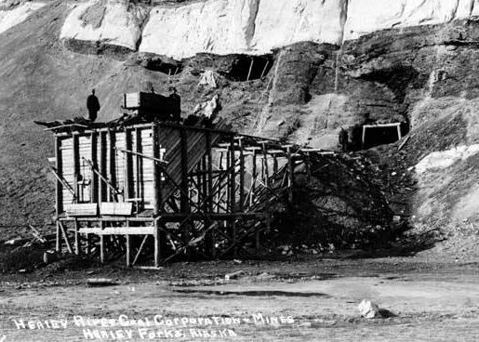

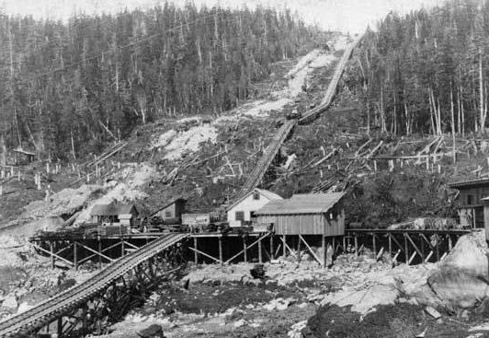

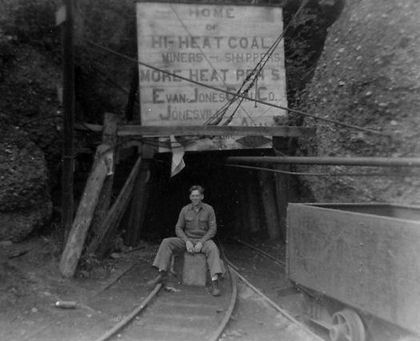

Coal mining in Alaska did not begin on a significant scale until 1917 after the construction of the Alaska Railroad had begun. Pre-World War II coal mining in Alaska was dominated by underground mining. An era of underground and surface mining followed from 1943 until the early 1960s. Recent coal production has all been by surface mining at the Usibelli Mine near Healy.

During the period beginning with World War I, and extending to the present time, coal has been mined predominantly in the Matanuska and Nenana coal fields. About one-third of Alaska's 32 million ton total coal production is estimated to have been produced in the Healy Creek Field of the Nenana Basin. Another one-third has been produced in the Lignite coal field, mostly near Poker Flat. The remaining one-third was produced in the Matanuska Valley and elsewhere in Alaska.

Katalla Coal Co. - Katalla, AK

Healy River Coal Corp. - Healy Forks, AK

Healy River Coal Corp. - Healy Forks, AK

Healy River Coal Corp. - Healy Forks, AK

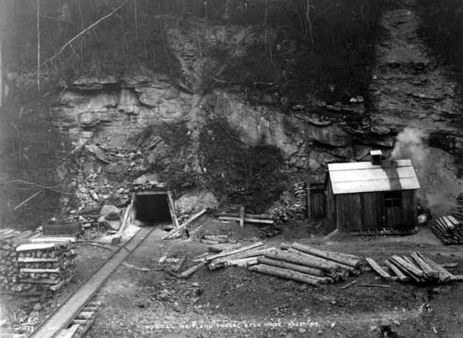

Coal mine - Lignite Creek, Denali Borough, AK

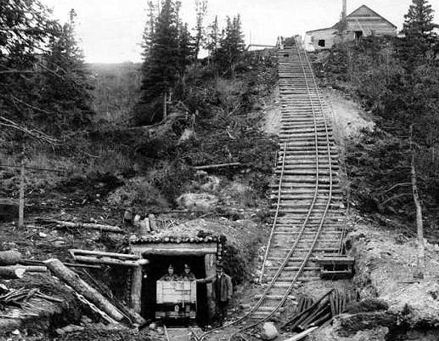

Underground - A.E.C. Coal mines - Eska, AK

A.E.C. Coal mines - Chickaloon, AK

A.E.C. Coal mines - Eska, AK

Chicago Creek Coal Mine - Chicago Creek, Seward Peninsula, AK

Healy River Coal Corp. - Healy Forks, AK

Maitland Portal - Eska, AK

Mining claim No. 1 - Dry Creek, Alaska 1901

Gold panning - Nome, AK

Snyder's Group of placer mines - Gold Hill & Peluck Creek, near Nome, AK

T.A.K.Gold Mining Co. - Salmon Creek, Juneau, AK

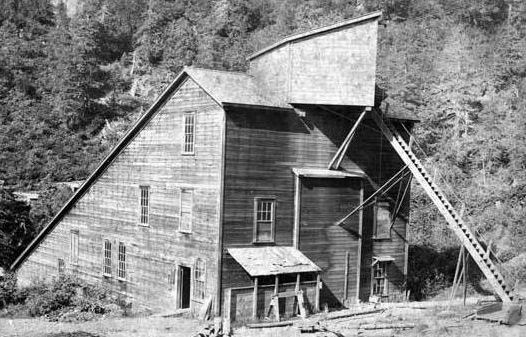

Ready Bullion Mine, Alalska Treadwell Gold Mining Co. - Treadwell, Douglas Island, AK

Alaska Treadwell Gold Mining Co. - Treadwell, AK

Alaska Gastineau Mine - Juneau, AK

Perseverance Gold Mining Co. - Juneau, AK

Ebner Gold Mining Co.'- Silver Bow Basin, AK

Ebner Gold Mining Co.'- Silver Bow Basin, AK

The center of copper-mining activity is Prince of Wales Island, where the earliest important developments were on the west coast, at or near Hetta Inlet, in the Copper Mountain, Jumbo, Red Wing, and Corbin mines. At Copper Mountain a 250-ton smelter was constructed and operated, while long tramways and wharves were built at Niblack, Skowl Arm, Karta Bay, Hetta Inlet, etc. Saw-mills and shops were erected and operations were usually by power, steam, or water.

Later there were very valuable deposits developed on the east coast, on and near Kasaan Peninsula, for which a smelting plant of 350 tons capacity was built and operated at Hadley, which has become a considerable centre. In 1907 there were thirty or more copper mines in process of development or operation on Kasaan Peninsula, which had become the principal copper-producing region of Alaska. The most important of the developed mines are those operated by the Brown-Alaska, Hadley-Consolidated, Mount Andrew, and Rust and Brown mining companies. There are other copper mines, promising or producing, on or adjoining Karta and Tolstoi Bays, Moira Sound, Skowl Arm, and also on Gravina Island opposite Ketchikan.

While the low price of copper caused several mines to suspend operations during 1908, there was an output of about 2,000 short tons of copper that year.

Evan Jones Coal Mine - Jonesville, Alaska