Mining contributed significantly to preventing potential bankruptcy for the early colonies in Australia. Silver and later copper were discovered in South Australia in the 1840s, leading to the export of ore and the immigration of skilled miners and smelters. The first economic minerals in Australia were silver and lead in February 1841 at Glen Osmond, now a suburb of Adelaide in South Australia. Mines including Wheal Gawler and Wheal Watkins opened soon after. The value of these mines was soon overshadowed by the discovery of copper at Kapunda in 1842, Burra in 1845 and in the Copper Triangle (Moonta, Kadina and Wallaroo) area at the top of Yorke Peninsula in 1861.

The first gold rush in Australia began in 1851 when prospector Edward Hargraves claimed the discovery of payable gold near Bathurst, New South Wales at a site Edward Hargraves called Ophir. Eight months later, gold was found in Ballarat and Bendigo in Victoria causing large influxes of prospectors. Australia's total population more than tripled from 430,000 in 1851 to 1.7 million in 1871.

Gold was first officially discovered in Australia on 15 February 1823, by assistant surveyor James McBrien, at Fish River, between Rydal and Bathurst in New South Wales. McBrien noted in his field survey book "At E. (End of the survey line) 1 chain 50 links to river and marked a gum tree. At this place I found numerous particles of gold convenient to river." Then in 1839, Paweł Edmund Strzelecki geologist and explorer, discovered small amounts of gold in silicate at the Vale of Clwyd near Hartley, and in 1841 Reverend W.B. Clarke found gold on the Cox's River, both locations on the road to Bathurst.

The finds were suppressed by the Colonial government to avoid a likely dislocation of the relatively small community. It was feared that convicts and free settlers would leave their assigned work locations to rush to the new find to seek their fortunes, in particular damaging the new pastoral industry. Reportedly Governor George Gipps said to Reverend W.B. Clarke when he exhibited his gold; “Put it away, Mr Clarke, or we shall all have our throats cut.” Recent evidence shows another find by William Tipple Smith near Ophir in 1848 was also kept quiet until the government was ready to exploit the resource.

The California Gold Rush started in 1848, immediately people began to leave Australia for California, to stem the exodus the New South Wales colonial government decided to alter its position and encourage the search for payable gold. In 1849 the colonial government sought approval of the Colonial Office in England to allow the exploitation of the mineral resources of New South Wales. A geologist was requested and this led to the appointment of Samuel Stutchbury. A reward was offered for the first person to find payable gold.

The discovery of gold was literally the discovery that changed a nation. Twenty-eight years after the Fish River discovery a man named Edward Hargraves discovered a 'grain of gold' in a waterhole near Bathurst, this was in 1851.

Hargraves had recently returned to New South Wales from the California goldfields where he was unsuccessful, however, he decided to begin his search for gold in New South Wales. The geological features of the country around Bathurst, with its quartz outcrops and gullies, seemed similar to those of the California fields. In February 1851 Hargraves and his guide John Lister, set out on horseback with a pan and rocking-cradle, to Lewis Ponds Creek, a tributary of the Macquarie River close to Bathurst. On 12 February 1851 they found gold at a place he called Ophir in his own words, once in the creek bed he somehow felt surrounded by gold. Initially keeping the find secret he travelled to Sydney and during March he met the Colonial Secretary. Soon the claim was recognised and Hargraves was appointed 'Commissioner of Lands'. He also received a £10,000 reward from the New South Wales government, plus a life pension, and a £5,000 reward from the Victorian government, however due to a dispute with his partners some of the reward was withheld.

The find was proclaimed on May 14, 1851 and within days the first Australian gold rush began with 100 diggers searching for their gold. By June there were over 2000 people digging around Bathurst, and thousands more were on their way. In 1852, the yield was 850,000 ounces (24½ tons). The great western road to Bathurst became choked with men from all walks of life, with all they could carry to live and mine

Largely due to the gold receipts into the colonial government treasury bringing immense wealth to the colony of New South Wales, the British Government, in 1854, authorised the establishment of the Sydney Mint. This was the first Royal Mint to be established outside of England. Ten years after the start of the gold rush in 1851 the population of New South Wales had grown from 200,000 to 357,000 people, an increase of 78%.

Discontent among the diggers grew as the government imposed restrictions and fees on mining. A monthly fee of 30 shillings was difficult to pay when the size of the claim per miner allowed only 13½ surface square metres. At the Turon fields near Bathurst the diggers were threatening to riot if fees were not reduced. Governor Fitzroy agreed and cut the fee by two-thirds but refused to change the collection method, known as 'digger hunts'. This involved police raiding a gold field and seeking out diggers who had not paid their fees. The offending diggers would be removed and taken before a Magistrate fined £5 for the first offence and double for each subsequent offence.

Another aspect of discontent had a racial tone. Leading up to 1861 the population of Lambing Flat, now known as Young, grew to 20,000. Of that number 2,000 were recent Chinese immigrants and this created significant tension leading to a riot in 1861. The official Riot Act was read to the miners on the 14th July 1861.

A very productive gold field surrounded the area of Hill End, New South Wales. This is the location of the worlds largest piece of gold-bearing material, a mixture of slate and gold weighing 235 kilograms, known as the Holtermann's Nugget. The nugget was found by a Bernhardt Holtermann in 1872.

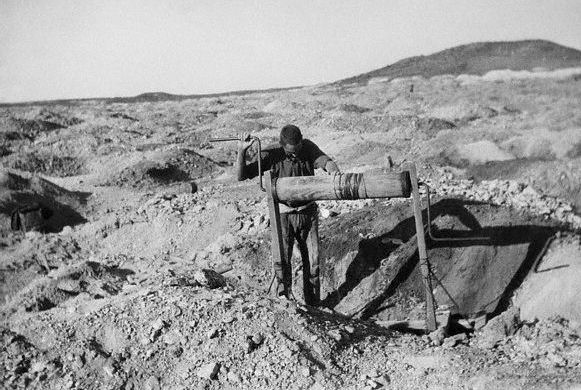

First obtained was the alluvial gold found on the surface. It is reported that when miners first arrived on the Mount Tarrengower fields, nuggets were picked up without digging. This was followed by exploitation of alluvial gold usually in creeks and rivers. The seekers used gold pans, puddling boxes and cradles to separate this gold from the dirt and water.

As alluvial gold ran out, underground or deep lead mining began. This was harder and dangerous. Locales such as Bendigo and Ballarat saw great concentrations of miners as teams and syndicates sank shafts. Coupled with erratic and vexatious policing and licence checks, tensions flared around Beechworth, Bendigo and Ballarat. These tensions culminated in the Eureka Rebellion of 1854. Following the rebellion, a range of reforms gave miners a greater democratic say in resolving disputes via Mining Courts and an extended electoral franchise.

In 1882, small finds of gold were being made in the Kimberley region of Western Australia, prompting in 1883 the appointment of a Government Geologist. In 1884 Edward Hardman, Government Geologist, published a report that he had found traces of gold throughout the east Kimberley, especially in the area around the present-day town of Halls Creek.

In 1885, following an 1872 offer by the Western Australia government of a reward of £5,000 for the discovery of the colony's first payable goldfield, a discovery was made at Halls Creek, sparking a gold rush in that state.

On 14 July 1885, having been prompted by Hardman's report, Charles Hall and Jack Slattery found payable gold at what they called Halls Creek, in the Kimberleys, Western Australia. After working for a few weeks Hall returned to Derby with 200 ounces of gold and reported his find. Once this discovery became known it prompted the Kimberley Rush, the first gold-rush in Western Australia. It is estimated that as many as 10,000 men joined the rush. On May 19, 1886 the Kimberley Goldfield was officially declared.

Thousands of men made their way to the Kimberley from other parts of WA, the eastern colonies, and New Zealand. Most arrived by ship in Derby or Wyndham, and then walked to Halls Creek. Others came overland from the Northern Territory. Most had no previous experience in gold prospecting or of life in the bush. Illness and disease were rife, and when the first warden, C D Price, arrived on 3 September 1886, he found that ‘great numbers were stricken down, in a dying condition, helpless, destitute of money, food, or covering, and without mates or friends simply lying down to die’. A few were lucky enough to locate rich alluvial or reef gold, but most had little or no success.

In the early days of the gold rush no records or statistics were recorded for either arrivals or deaths. Also nobody knows how many died trying to get to Halls Creek across the waterless desert, or how many simply turned back. When men actually arrived at Halls Creek, dysentry, scurvy, sun-stroke and thirst continued to take its toll. The Government applied a gold tax of two shillings and sixpence an ounce. It was a very unpopular levy as gold proved so hard to get. The diggers avoided registering and the Government had a great deal of trouble collecting the tax or statistics of any kind.

When the first warden C.D. Price arrived in September 1886 he reported that about 2,000 remained at the diggings. By the end of 1886 the rush had ceased. When in May 1888 the government considered claims for the reward for discovery of the first payable goldfield, it was decided that the Kimberley goldfield, which had proven disappointing, and no reward was paid out as the field had not met the stipulated conditions of a yield of at least 10,000 ounces (280 kg) of gold in a 2-year period passing through Customs or shipped to England. (It is estimated that as much as 23,000 ounces [650 kg] of gold was taken from the fields around Halls Creek, but with much leaving the field through the Northern Territory). Hardman's contribution was recognised, however, with a gift of £500 to his widow Louisa Hardman. Another £500 was given to Charles Hall and his party.

In September 1892 gold was found at Fly Flat (Coolgardie) by Arthur Wesley Bayley and William Ford, who next to a quartz-reef obtained 554 ozs (15.7 kg) of gold in one afternoon with the aid of a tomahawk. On 17 September 1892 Wesley rode the 185 km (115 miles) with this gold into Southern Cross to register their reward-claim for a new find of gold. Within hours had started what was at first called the Gnarlbine Rush. Overnight the miners who were flocked on the Southern Cross diggings moved to the more lucrative Coolgardie Goldfield. The reward claim for Bayley's party for discovering the new goldfield was to be granted a 100 foot (30.5 metre) deep claim along the line of reef. This claim was said to cover an area of five acres (2 hect.). On August 24, 1893, less than a year after Arthur Bayley and William Ford's discovery of gold at Fly Flat, Coolgardie was declared a town site, with an estimated population of 4,000 (with many more mining out in the field).

The Coolgardie goldrush was the beginning of what has been described as "the greatest gold rush in West Australian history". The greatest movement of people in Australia's history was in the period 1851 to 1861 during the gold-rushes to the Eastern states when the recorded population of Australia rose by 730,484 from 437,665 in 1851 to 1,168,149 in 1861, as against an increase of 20% of this amount for Western Australia in the period 1891 to 1901, a 137,834 increase of recorded population for Western Australia from 46,290 in 1891 to 184,124 in 1901.

On 17 June 1893 alluvial gold was found near Mount Charlotte, less than 25 miles (40 km) from Coolgardie, at what became the town of Hannan (Kalgoorlie). The announcement of this find by Paddy Hannan only intensified the excitement of the Coolgardie gold-rush, and led to the establishment in Western Australia's Eastern Goldfields of the twin towns of Kalgoorlie-Boulder. Prior to moving to Western Australia in 1889 to prospect for gold Hannan had prospected at Ballarat in Victoria in the 1860s, Otago in New Zealand in the 1870s, and at Teetulpa (north of Yunta) in South Australia in 1886.[33] The first to find gold at Kalgoorlie were Paddy Hannan and his fellow Irishmen Thomas Flanagan and Daniel Shea. Unbeknownst to them, they had discovered an area that would eventually rank as one of the most productive gold regions on earth – the Kalgoorlie Golden Mile.

After Hannan, the only literate one among the three men, registered their reward-claim for a new find of gold with over 100 ounces (2.8 kg) of alluvial gold, an estimated 700 men were prospecting in the area within three days. The reward for Hannan's party for discovering the best alluvial find ever made in the colony, and without knowing it one of the best reefing fields in the world, was to be granted a six acre (2.4 hectare) mining lease.

Gold was found in Queensland near Warwick as early as 1851, beginning small-scale alluvial gold mining in that state.

The first Queensland goldrush did not occur until late 1858, however, after the discovery of what was rumoured to be payable gold for a large number of men at Canoona near what was to become the town of Rockhampton. According to legend this gold was found at Canoona near Rockhampton by a man named Chappie (or Chapel) in July or August 1858. The gold in the area, however, had first been found north of the Fitroy river on 17 November 1857 by Captain (later Sir) Maurice Charles O'Connell, a grandson of William Bligh the former governor of New South Wales, who was Government Resident at Gladstone. Initially worried that his find would be exaggerated O'Connell wrote to the Chief Commissioner of Crown Lands on 25 November 1857 to inform him that he had found "very promising prospects of gold" after having some pans of earth washed. Chapel was a flamboyant and extrovert character who in 1858 at the height of the goldrush claimed to have first found the gold. Instead Chapel had been employed by O'Connell as but part of a prospecting party to follow up on O'Connell's initial gold find, a prospecting party which, according to contemporary local pastoralist Colin Archer, "after pottering about for some six months or more, did discover a gold-field near Canoona, yielding gold in paying quantities for a limited number of men". O'Connell was in Sydney in July 1858 when he reported to the Government the success of the measures he had initiated for the development of the goldfield which he had discovered.

This first Queensland goldrush resulted in about 15,000 people flocking to this sparsely populated area in the last months of 1858. This was, however, a small goldfield with only shallow gold deposits and with no where near enough gold to sustain the large number of prospectors. This goldrush was given the name of the 'duffer rush' as destitute prospectors "had, in the end, to be rescued by their colonial governments or given charitable treatment by shipping companies" to return home when they did not strike it rich and had used up all their capital. The authorities had expected violence to break-out and had supplied contingents of mounted and foot police as well as war ships. The New South Wales government (Queensland was then part of New South Wales) sent up the "Iris" which remained in Keppel Bay during November to preserve the peace. The Victorian government sent up the "Victoria" with orders to the captain to bring back all Victorian diggers unable to pay their fares; they were to work out their passage money on return to Melbourne.

In late 1861 the Clermont goldfield was discovered in Central Queensland near Peak Downs, triggering what has been described as one of Queensland's major gold rushes. Mining extended over a large area, but only a small number of miners was involved. Newspapers of the day, which also warned against a repeat of the Canoona experience of 1858, at the same time as describing lucrative gold-finds reveal that this was only a small goldrush. The Courier" (Brisbane) of 5 January 1863 describes "40 miners on the diggings at present"..."and in the course of a few months there will probably be several hunderd miners at . "The Courier" reported 200 diggers at Peak Downs in July 1863. The goldfield covering an area of over 1600 square miles (4000 square km) was officially declared in August 1863. "The Cornwall Chronicle" (Lanceston, Tasmania), citing the "Ballarat Star", reported about 300 men at work, many of them new chums, in October 1863.

In 1862 gold was found at Calliope near Gladstone, with the goldfield being officially proclaimed in the next year. The small rush attracted around 800 people by 1864 and after that the population declined as by 1870 the gold deposits were worked out.

In 1863 gold was also found at Canal Creek (Leyburn) and some gold-mining began there at that time, but the short-lived goldrush there did not occur until 1871–72.

In 1865 Richard Daintree discovered 100 km (60 miles) south-west of Charters Towers the Cape River goldfield near Pentland in NorthQueensland. The Cape River Goldfield which covered an area of over 300 square miles (750 square km) was not, however, proclaimed until 4 September 1867, and by the next year the best of the alluvial gold had petered out. This goldrush attracted Chinese diggers to Queensland for the first time. The Chinese miners at Cape River moved to Richard Daintree's newly discovered Oaks Goldfield on the Gilbert River in 1869.

The Crocodile Creek (Bouldercombe Gorge) field near Rockhampton was also discovered in 1865. By August 1866 it was reported that there were between 800 and 1,000 men on the field. A new rush took place in March 1867. By 1868 the best of the alluvial gold had petered out. The enterprising Chinese diggers who arrived in the area, however, were still able to make a success of their gold-mining endeavours.

Gold was also found at Morinish near Rockhampton in 1866 with miners working in the area by December 1866, and a "new rush" being described in the newspapers in February 1867 with the population being estimated on the field as 600

The probable occurrence of tin in New South Wales was first referred to by the Rev. W. B. Clarke as early as 1849, while the same author noted having obtained a specimen in the Kosciusko district in 1861 and in the New England district in 1863. He also reported the discovery of stanniferous deposits at different localities in the Darling Downs, Queensland. In 1872 the Messrs. Fearby discovered tinstone near Inverell, and the present Elesmore mine was opened near the spot. The news of the discovery of tin in the New England district attracted a mild rush, and in March, 1872, valuable deposits of stream tin were found at Vegetable Creek. It is interesting to note that native tin, which is extremely rare, was discovered at Oban in this district. At Cope’s Creek stanniferous gravels occur in the channel of the stream and in the slopes adjacent to it. Post-tertiary deposits of tin-bearing ore were found at Emmaville, where mining was commenced soon after the opening of the district. In the southern portion of the State deposits were discovered at Dora Dora, near Albury, and Pulletop, near Wagga, in the central-western district at Burra Burra, near Parkes, and in the far west at Poolamacca and Euriowie. The bulk of the yield, however came from the Tingha-Inverell district, the production lin 1908 being £117,600, out of a total for the whole State of £205,447. Of the total production in 1908 £129,952, or 60 per cent., represents the value obtained by dredging. In 1908 the Sydney smelting Company at Woolwich dealt with 1500 tons of ore obtained from the tin-fields of the State, the value of theprouct being estimated at £135,460.

In Victoria lode tin was discovered at Mt. Wills, Beechworth, Eldorado, Chiltern, Stanley, and other places in the north-eastern district; and stream tin was found in a large number of places, including those just mentioned in the north-eastern district. The bulk of the production in 1908 was obtained by dredging and hydraulic sluicing, the chief yields being 39 tons of ore, valued at £3289, raised in the Beechworth district, and 23 tons, valued at £1555, raised at Toora.

The first notable discovery of tin in Queensland occurred in 1872, when rich deposits of stream tin were found in the country to the south of Warwick and on the borders of New South Wales. This district proved to be surprisingly rich, the value of the metal raised there during the five years subsequent to its discovery being £715,000. The alluvial deposits, however, soon became exhausted, so far as the ordinary miner was concerned, but some degree of success was attended dredging operations in the district. In 1879, important discoveries were made in the Herbert River district, and the rich Herberton, Walsh, and Tinaroo mineral fields were opened up, further discoveries being shortly after reported on the Russell, Mulgrave, Jordan, and Johnstone. At the Annan River tinfield, near Cooktown, alluvial mining was carried on continuously since 1886. The production in 1908 amounted to 4825 tons, valued at £342,191, more than three-fourths of which were produced by the Herberton mineral field.

Valuable lodes of tin were found in the Northern Territory at Mount Wells, West Arm and Bynoe Harbour, and at Horseshoe Creek, south of Pine Creek, but the deposits had not been exploited to the extent they deserved. In 1908 there were 304 miners engaged in tin mining in the Northern Territory and the quantity of tin ores and concentrates exported was 447 tons, the highest yet recorded to date. This increase was entirely due to the progress at the Mount Wells mine, where, it was stated, there are enormous bodies of payable material awaiting development. The metal has also been discovered near Earea Dam in the province proper.

Tin was first discovered in Western Australia in the year 1888. and since that date was found in several widely distant localities in the State - at the head of the Bow and Lennard Rivers, in the Kimberley district; on the Thomas River Gascoyne goldfield; at Brockman’s Soak and the Western Shaw, in the Pilbara district; and at Greenbushes, in the south-western portion of the State. The production of tin ore and ingot for the State during 1908 amounted to 1,093 tons, valued at £83,296, to which the Greenbushes field contributed 576 tons, valued at £41,046, and Pilbara 403 tons, valued at £30,636. Lode tin was discovered at Wodgina, in the Pilbara field, and the deposits were further developed.

Tin mining in Tasmania dates from the year 1871, when the celebrated Mount Bischoff mine was discovered by Mr. James Smith. This mine, which at the time was probably the richest in existence, was worked as an open quarry, and a large proportion of the original hiill was removed in the course of development operations. Soon after which deposits were located in the north-east district by Mr. G. B. Bell, while deposits of stream tin were discovered near St. Helens by Messrs. Wintle and Hunt. Further finds were reported from Flinders and Cape Barren Islands, and in 1875 the metal was discovered at Mount Heemskirk. The total production of Tasmania in 1908 was 4,621 tons of Ore, valued at £421,580, the largest producer being the Briseis Tin Mines Limited, in the North-east division, with a return of 1,047 tons. this his company distributed during the year £60,000 in dividends. The Mount Bischcoff mine paid dividends amounting to £36,000, making a total to the end of 1908 of £2,160,000. Good returns were obtained at the North-East Dundas and at Mount Heemskirk, and a fair amount of alluvial was furnished by the Eastern mining division. Other mines in the Western division were prospected, and some very rich deposits were discovered.